Transcript

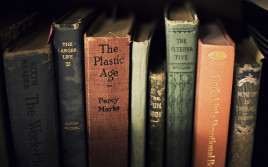

This podcast is about the books that have been forgotten, the literature that no one reads any more.

Dr. Kate Macdonald is a lecturer in the English Department at the University of Ghent, in Belgium. She seeks to uncover the or are no longer in print. Kate’s research practice operates against the grain, against the prescribed greats that we are told we should read, which still dominate university reading lists and benefit from the ‘vintage’, ‘classic’ or ‘essential’ status which helps to keep them in print. Instead, Kate actively looks for the unread, neglected and abandoned in search of a brilliant or unusual story. Her quest for and analysis of ‘forgotten fiction’ begins with a story of its own, with a rummage, with a hunt, with a dig into the wonderful world of secondhand print. Kate invited me to join her at Skoob Books in London, a secondhand bookshop full of untold treasures.

Will Viney: Kate, you’ve made a discovery.

Kate Macdonald: Yes, this is one I’ve been looking for some time. It’s Sorrel and Son by Warrick Deeping. He was a huge bestseller in the 1920s, 30s and 40s but now he’s really despised – nobody likes him – he’s beginning to be discussed in a critical way but only because he was such a malevolent, nasty, angry man. And this book is supposed to be one of the classics so I need to read him, because I’m interested in male writers of the interwar period.

WV: Particularly angry men?

KM: Angry men are good because angry men make an emotional response to their times that their really desperate to express and convey to other people. I want to know what those messages are, that’s why I write about the ‘masculine middlebrow.’

WV: So Deeping is angry: is his public persona angry or is his fiction angry? Is this a case of the ‘cult of the author’ preceding the ‘cult of the work’?

KM: That’s the thing: I don’t know very much about him other than the little amount of critical literature there is on him. Apparently he was a genuinely angry bloke. I’d like to know if his fiction is also angry and, if so, what was it about? Then, can I go back to the critical literature and say, actually I don’t agree, or yes, I do agree but not in this case. So in a way it is helping me make my own mind up.

WV: In a way, one of the pleasures of being in bookshops of any kind, but particularly book shops like this, which has such a collection – really, a collection of many different, myriad collections that have found their way, one way or another, into this single room – is that you can wander around and, even if you’re not interested in buying anything, you have those reminders of particular times or particular encounters with writers.

KM: Yes. When I come to a bookshop like this I will go in with one or two books in mind or writers in mind that I know I’m looking for and I’m just checking up on what they’ve got. And then I just browse. And sometimes you get the feeling that you mustn’t stop browsing, there’s something here, just keep looking, don’t focus just keep browsing and then I usually find something that’s really good.

WV: So the method of collection for you is just sheer activity, it’s just doing?

KM: Yes, it’s being there. It’s stock taking, it’s seeing what’s on the shelves: ‘oh, that looks interesting’; ‘oh, good, I’ve been looking for this’; ‘that looks extraordinary, I’ve never heard of it, what’s this about.’ So yes, it is serendipity and it is being there at the right time.

WV: I think it was Aby Warburg who believed that the book that you want is next to the one that you thought you were after.

KM: Yes, that’s very often true – or the book you really want is the one you can’t read the spine of because it’s on the bottom shelf and it’s so dusty and so faded by sun that you have to get down on your knees, pull it out and look at it. Then have hysterics because, if you’re a collector, it’s a first edition or because didn’t think you could ever find this particular copy. That’s really exciting.

WV: Partly because you’ve been burrowing around? This is the physical labour of it…

KM: You’ve got your hands dirty – I always come out of a bookshop with filthy hands. I’m in there, in the dust, just pulling things out to see what no one else has touched and what other people have missed.

WV: This is the archaeology of the literary critic!

KM. It is. It’s interesting how bookshops allow the dust to accrue. They have these books in beautiful order here but there are still dusty heaps.

WV: It marks the difference between a bookshop like this and one, say, in a major contemporary art museum where no digging is required. Everything in labelled, everything is there; everything you hope will be there is probably there.

KM: This shop is less like one in a gallery or museum; this is a huge collection which has been ordered up to a point. The way this has been ordered is by, ‘this can be sold for money, people might want this.’ They wouldn’t sell really tatty copies of books because no one would want to buy them, with ragged spines or on subjects that are really not interesting. But the question of the literary value is utterly personal to the buyer because the book I’m now holding in my hand I’d quite like, whilst someone else might think, ‘good Lord, put it in the bin! It’s really valueless.’ That’s what really matters.

WV: It’s odd, isn’t it? I’m seeing the way that you grip this book. I know the feeling – you go into a secondhand bookshop and you make this great discovery and you then think, ‘my goodness. If I want this then there’s almost certainly someone else – in the shop right now! – that wants it too.

KM: Yes, if I put it down they’ll take it. I’ve got to hold it; I can’t put these in a stack except behind the counter.

WV: In a regular bookshop if you put a book somewhere it looks out of place, thus not for general perusal by someone else. Whereas in a bookshop like this, although it’s very well organised, you know that if you put it down it’s fair game.

KM: It is, someone else will take it or tidy it. These stacks here could be someone’s choice who hasn’t come back from this morning’s browsing; it’s impossible to tell.

—-

To get away from the din and clatter of a commercial bookshop we found a quiet room in which to continue our conversation about forgotten fiction. It’s with no small irony that our room was on Gordon Square, the Wembley Arena of the literary establishment, and an excellent place in which to discuss the worth of the so-called literary lower leagues.

—-

WV: So, Kate, you don’t do what most literary critics do.

KM: No, I don’t – what do I do? My first degree started off being a history degree but I failed every single exam apart from my English exam, which was a minor. And so I completed my English degree and then took a Ph.D in English and it became fairly obvious that English was my thing. But I can never forget that I was an historian a very long time ago. So now that’s what I am: I’m a literary historian and the kind of history I do is print culture, book history and the history of reading – the books that people used to read and why.

WV: And the books that some people no longer read?

KM: Yes, the books that people now have no idea about. Such as the books that were read by my grandparents, your great-grandparents and my great-grandparents, that no one has even heard of.

WV: And you’ve called this ‘forgotten fiction’ – is this your term?

KM: No a journalist friend called it that.

WV: Could you say what it means?

KM: Forgotten fiction: the books that have really heard of in the sense that they’ve never read them but they may, possibly, have some memory of the title. So, if I said a title like 84, Charing Cross Road you might think, ‘uh, I’ve heard of that… wasn’t it a film?’ Very people will go back and think, ‘that was a book and a major best-selling book.’ Then it was made into a film, then it was made into a TV series. So it’s the root of the matter, you have this layer of cultural stuff but at the bottom there’s this book.

WV: Perhaps we could put it like this: part of your work is to clear away some of this noise and get back to, not to the origin of the thing, but certainly its textual manifestation.

KM: Yes I think that’s true. I think clearing away the … ‘clutter’ is the wrong word, I don’t want to be pejorative … going back to the beginning, going back to the book that first said these things, the first expression of these thoughts, the first recording of this moment in time and these feelings. That’s what I like to look at.

WV: Are there any criteria that you use to select a forgotten work for analysis and appraisal?

KM: I think my first criterion would be – do I enjoy reading it? There’s no point in working on a book if you can’t physically bring yourself to touch it or if you find a miserable experience. I’ve got to enjoy reading it. And that might not be true pleasure, it might also be that this is a really exciting book because I get so angry about it. Or this is a book that really makes me fizz with frustration because I want to express a rejoinder in reading it. So I guess an emotional response, that’s what is important.

WV: OK, so you’ve found a book you really like and you look about and you’re not really seeing an awful lot of critical literature or other people writing about this work. What do you do?

KM: Well I’ve decided to do podcasts mainly because I prefer podcasts than I do reading book blogs, although I do read book blogs I like listening. So what I’ve got is a weekly podcast called ‘Why I Really Like this Book’, it has it’s own site – www.reallylikethisbook.com – you can find it on iTunes, Blackberry and on Miro, an American site and one that seems to get a lot of traffic. There’s also a Facebook page. So every week, every Friday morning at 1.30am, British time, the podcast is released to a waiting world.

I’m working my way through the alphabet for authors. I started with ‘A’ for Allingham and ‘B’ for Buchan, ‘C’ for Colette. I’m now at letter ‘R’. The plan is that when I get to Z I’ll start to do a theme and I think the first one will be good old-fashioned detective fiction, then I’ll go on to British science fiction and fantasy novels, something like that. What has been fascinating is when I’ve been stuck at a letter and I had to really work to find an author. So I did not have any authors beginning with the letter ‘I’ so I looked in the biography section of my house and found Molly Izzard’s Freya Stark: A Biography. And that was brilliant because it gave me so much to talk about, how biography works, what you expect when you read a biography, it was a good episode and I’m proud of that one. ‘Q’ has been hard but again I twisted it and I talked about the critic, Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch, and I ended up talking about the nature of criticism as a student might see it. ‘X’ is going to be a Chinese author, I don’t think there’s any way of getting round that, ‘Z’ will be a Spanish one. I’ve got them lined up and that’s the challenge.

WV: It seems to me that you’re making a platform for your work with your podcasts. I’m really interested in this because one of the structural and integral parts of studying, gathering and foraging for ‘forgotten fiction’ is that there isn’t that community that you might find with Woolf or Eliot or Spenser or Dryden or whoever.

KM: It’s difficult to gauge what the community might be for forgotten fiction because with my podcast series people will dip in, chose the authors they’re interested in, and then not ever come back. I don’t know how many people are out there who are thinking, ‘I’ve got to know about every single one!’ It’s a very difficult thing to understand. I think what I’d like is for more people to talk to each other. I think the podcast series is just a way for me to tell people that go to book groups, people like my mother, people like my students, who are interested in reading, who want to read but also want to be pointed in different directions that they may not have thought of before.

WV: There’s something about finding forgotten fiction that seems to me to resonate with hunting. There must be certain moments, certain hunts, certain trophies which somehow encapsulate both the spirit of some of your research and the history of that research?

KM: The history of the hunt is fascinating. My favourite hunts begin with nothing at all. A small, small thing that I may not have noticed and then the hunt may not have occurred. Someone once sent me a book review. It was a photocopy from a 1930s magazine and the book review was about the author John Buchan, on whom I’ve done a lot of research. I read the review and I said, well, this is useful and I’ll add it to my little file and then, ‘what is that?!’ In the review there was a mention of another author who I had never heard of: Una L. Silberrad. Silberrad, that’s a name not easily forgotten and there are only two Silberrads publishing in the twentieth century, so, in the event, she’s easy to track down. Even so, how could I have missed this writer? I have spent most of my life looking in second-hand bookshops and trawling through charity bookshops and jumble sales, that sort of thing, looking for books. So I started to research her – straight to the British Library. Who was she? My goodness, she’s published 44 novels! How could I have missed her?! And so the hunt just continued. Most of it was done on the internet because I live in Belgium ad it’s difficult for to find many second-hand bookshops with English books and the Belgian ones I know were completely out of stock. On the internet I began to buy books at very cheap prices but what was really interesting was that they were very low cost – £2-£3, which is low for an Edwardian or First World War-period novel – but there were very few copies, sometimes only two copies on the market in the whole world. That’s just bizarre. So I started to buy. With a little more research I discovered two other people that were looking into her at an academic level and also just in personal interest. I got in touch with the family who were very pleased to hear that somebody else was interested in great-aunt Una’s books and I went back to the internet to do more hunting and then I find the books have now doubled in price, those that are left, and that the print-on-demand industry had really taken notice and suddenly all her books were available as print-on-demand texts for at least £20, if not more. And that just shows you that the internet takes notice, the online printing industries are very clever, they have little bots that go about catching up with the searches. So now I’m stuck. Have 19 of her 44 novels. I’ve done a lot research and I’ve done a lot of writing about her. Other people are collaborating so things are moving.

WV: Have you got a reputation?

KM: I have a reputation in a very small area [laughs].

WV: I meant, have you got a reputation for collecting because when you put your name out as someone that is really interested in getting a certain author’s works then the spider’s web stretches for you and people come into play.

KM: It’s never occurred to me that me, myself, would actually be noted as someone doing the hunting. I’ve never noticed that someone has identified me as looking for a particular author, except when … on Amazon, but Amazon does that all the time. I will look for birthday presents and for a ten year-old niece and next time I go on I’ll find all sorts of suggestions for toys for ten year-olds. But that’s not quite the same. I don’t get publishers catalogues sent to me on spec so, no, I’m not a collector, that’s probably the difference. I’m not buying high-end books, I’m not spending a lot of money. I have book-collecting friends who do spend a fortune. They will spend £200 or £300 on an edition. Because it’s a first edition, because it has a dust wrapper, for whatever reason. I don’t have that sort of money and I don’t want to spend that sort of money; I just want a reading text, a book that I can look at.

WV: Nevertheless, the market does respond to you. It sounds like you’re in a minority when searching out this author’s work but I’m interested in this relationship between searching out forgotten fiction on the one hand and revival on the other. And so, I wonder, it sounds as if this author’s work is still a long way from being a household text – everyone has it on their shelves – but at what point does a ‘forgotten’ work become ‘remembered’?

KM: There are some publishing houses which have a very enlightened attitude to rescuing forgotten fiction, Virago in Britain is the most well known as they have made their reputation by rescuing women’s writing of the early twentieth century. Other publishing houses followed suit: The Women’s Press and also Persephone Books. Now, these houses need to exist, they have to publish books that have to sell. Persephone Books has made a special for rediscovering and representing the work of Dorothy Whipple who is a really excellent writer of the 1930s and 40s. That’s their pet thing. I’ve tried presenting Una Silberrad to these publishing houses and they’re not interested in their own good, commercial reasons and that’s fine; I have no problem with that. If they don’t feel that they can sell the work or that writer does not fit within their remit, within the group of writers they already publish, they’re not going to want to try it.

WV: While the doors might be open in 1900 or 1910 for some of these writers, or whenever, they might be firmly closed now.

KM: They’re firmly closed mostly in print but the internet has a lot of opportunities. It is certainly possible to print Una Silberrad’s novels for print on demand yourself. There are companies like Lulu, who will do reasonable design, fairly low-cost. You can do it but that’s not the kind of book I want, I want a real book.

WV: It’s extraordinary – I went into a bookshop in Boston recently and they had a print on demand machine, in the bookstore. So you could go to Guttenberg or any online repository of texts that are out of copyright, and could have your own copy printed in front of you in 15 minutes. It is the case that for many of the novelists that you’re interested in their copyright has expired. So one can conceivably print a copy for oneself. But you’re not interested that, why?

KM: I want the older feel of the book. I want to see the old typeface. I want to see who printed it originally. I want to see the adverts. The editions that I really like are ones that have adverts for other authors and their works. Also, if you’re lucky you get adverts for things like soapflakes and fabrics and coats and patent foods for babies. All the stuff, all that ephemeral and paratextual material gives you so much more information about the original readers that the original publishers envisioned would be buying that book.

WV: Because if you buy a print on demand book you buy a text but not some of the social history that surrounds it. Which is really your motivation.

KM: Well it’s part of the motivation. The story is still extremely important but the extra stuff I find just as interesting in many ways. A print on demand book in shiny modern photocopy paper, in glaring black ink, with a really inappropriate, shiny cover, I just don’t want it. I will only do that if I’m desperate and I’ve to read that book and there’s no other way of getting it.

WV: And of course, if you were to have your print on demand book there would be trip to the second-hand bookshop.

KM: Absolutely not, and then I wouldn’t find anything else and that would be very sad.

You’ve been listening to Will Viney and Dr. Kate Macdonald discuss the importance of forgotten fiction. There are plenty of other podcasts available on the Pod Academy website, so please visit podacademy.org.

Notes

Websites:

Subscribe to Kate Macdonald’s podcast series by visiting her website: http://reallylikethisbook.libsyn.com. Follow her on Facebook

Slightly Foxed is, according to their website, ‘the kind of good reads you knew you were looking for but somehow haven’t been able to find.’ We visited Skoob Books, an excellent and diverse secondhand bookshop in the Bloomsbury, London.

There are a number of blogs dedicated to the margins of English verse and prose, Vulpes Libris, Curious Book Fans, where Kate Macdonald has been a guest contributor, and Simon Thomas’ excellent site, Stuck-in-a-Book.

Selected readings:

Bennett, Andrew and Nicholas Roye, An Introduction to Literature Criticism and Theory. (Harlow: Longman, 2009), esp. ch. 6 on literary ‘monuments’.

Bloom, Harold. The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages. New York: Riverhead, 1995.

Culler, Jonathan. Literary Theory: A Very Short Introduction. (Oxford: OUP. 2011).

Tags: 84 Charing Cross Road, Aby Warburg, Allingham, Arthur Quiller-Couch, Books, Canon Formation, Colette, Dorothy Whipple, Forgotten Fiction, Freya Stark, John Buchan, Kate Macdonald, Literary Value, Lulu, Molly Izzard, Persephone Books, Print on Demand, reading, Secondhand, Skoob Books, The Women's Press, Una L. Silberrad, Virago, Warwick Deeping, Will Viney

Subscribe with…