Transcript

As the Syrian conflict demonstrates, crowd-sourced video footage and photographs are now an important part of any news reporting. But how do you verify what you are watching? In this lecture given in Spring 2013 and part of our Huston lecture series, Markham Nolan, Managing Editor of Storyful, the Irish news agency explains how news gathering has changed, and how the investigative skills of the journalist have to be developed to meet new challenges. With vivid case studies from Syria, the Arab Spring, hurricanes and earthquakes he demonstrates the tools Storyful uses for verifying crowd-sourced news. These tools are available to all of us on the internet, for free, and can be used to assess the veracity and news value of YouTube videos, tweets and posts on Facebook.

Markham Nolan: Storyful is an agency that was set up by Mark Little, a foreign correspondent for RTE, who, posted in Iran was watching stuff going on on the streets, seeing a lot of white-faced European reporters standing on hotel roofs about 20 miles away from the action, having to guesstimate what was going on in the streets. At the same time, he was looking at his own phone and seeing uploads from Iranian students and protestors being beaten in the streets and being chased down by the Iranian police. He made the connection – why isn’t this material on our television screens? Isn’t it closer to the truth than anything we are being shown?

And of course what we’re seeing now, especially since the Arab Spring, is a lot more amateur video, a lot more YouTube footage. What we do in Storyful is help news organisations (including some of the big ones like ABC in the US, Channel 4, New York Times) make all this social media useful. There was fear in those organisations about what could be verified or proved to be true, what was dodgy, what was fake? We apply old journalism techniques through a number of free internet tools, we look at social media and we verify. Our tagline is News from Noise, and one of our internal rules is, “there is always someone closer to the story.” And that is what I am talking about today. How, with digging and using clever internet tools, you can get closer to the source of a story.

Ireland has been an interesting place for journalism for a very long time. Take, for example, Thomas Crosby of The Examiner. In 1850 Thomas Crosby was 15 years old and he decided he was going to go into journalism and join the Cork Examiner – a regional paper in the South of Ireland. Within a short space of time he became one of the best foreign correspondents in Europe. He was scooping the London Times, scooping all the papers in Europe. And all he did was to get a little closer to the source than anyone else. How? He was from a boating family and he would row out into the middle of Cork harbour when a ship sailed in from across the Atlantic (a three week journey, before undersea cables or any other direct communication with America) and he’d shout up to the people on board and they’d shout back with news that was 3 weeks old but never heard before in Europe. He’d write it down, and they’d throw him a copy of the New York Times and he’d scan the papers for what he ould or couldn’t verify. So the Cork Examiner got it first, and beat the rest of Europe to the news of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address and the end of the American Civil War. They did that because Thomas Crosby had innovated a little bit in a rowing boat – he literally pushed the boat out a abit! That’s all it took to get closer to the source than anyone else. And we’ve taken that further and further. We can now talk directly to them.

We are currently in a period of upheavel for journalism and newspapers (all the money is being gobbled up by Google!) but also for news gathering. And this has come about because of a shift in the balance of power.

In the 150 years since Tomas Crosby the audience didn’t have any say in what the news was. They saw and consumed the news from journalists. There were letters pages, of course, but essentially there was a long loop into how anyone – you, me, anyone else – could affect the news, or could say, “I challenge what you’re saying, I challenge facts in your reporting,” or, “I don’t want to hear about this, I want to hear about something else.” That has really only changed in the last 5 years.

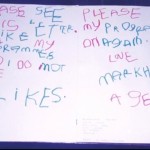

My first experience with the media, and pushing back against what was happening was 1984, when I was 4. There was a one day strike at the BBC and I couldn’t see my cartoons. I was angry and wrote a letter. They wrote back to me, and it took 3 weeks. In 1984, a 3 week loop.

My first experience with the media, and pushing back against what was happening was 1984, when I was 4. There was a one day strike at the BBC and I couldn’t see my cartoons. I was angry and wrote a letter. They wrote back to me, and it took 3 weeks. In 1984, a 3 week loop.

You can’t affect the news that way. But now you can. If you see something on line you can respond directly to the journalist – tweet them, email them – and if you don’t get a response in half an hour you begin to question what’s going on, “I have something valid to say, so what have they got to hide?” Or “Don’t they want to change their journalism?” That is how far we’ve come, between 1984 and now, instant feedback. And what that means is that journalists are more responsive, not just pushing out any more, but rather involved in a constant conversation with everyone in the world. It behoves us to immerse ourselves in that conversation and it also changes how we journalists do our job. You can’t just push the news, you have to react. We are working in real time. It poses huge challenges. But it also give us access to stuff at greater levels than we’ve ever had before.

Here is a picture of the site of an earthquake on September 5th in Costa Rica – a fairly big earthquake, 7.6 on the Richter Scale. It took a minute for the earthquake tremors to move 250km from Costa Rica to Nicaragua. And 30 seconds after that someone tweets about the earthquake. So in 90 seconds information about that earthquake is available to people all around the world. 3 weeks for Thomas Crosby, but now just 30 seconds from when someone felt the earth beneath their feet begin to shake.

Here is a picture of the site of an earthquake on September 5th in Costa Rica – a fairly big earthquake, 7.6 on the Richter Scale. It took a minute for the earthquake tremors to move 250km from Costa Rica to Nicaragua. And 30 seconds after that someone tweets about the earthquake. So in 90 seconds information about that earthquake is available to people all around the world. 3 weeks for Thomas Crosby, but now just 30 seconds from when someone felt the earth beneath their feet begin to shake.

What that should mean is that we can know about any event, anywhere in the world instantaneously. After all, what that person did in Latin America is what we all do now – document our lives in real time. You come to this conference today and you mention it on Twitter or Facebook. We are creating a real-time respository of everything that is happening now in the world. And every journalist – or another person – should be able to access that event for free in real time. It should mean we don’t have to miss a thing!

Except, there is too much information. 72 hours of video is uploaded onto YouTube every minute. Every single second there is 1hour 10 mins more on YouTube! On Facebook 2.5m photos are posted every 15 minutes. Could you ever catch up? It’s mind boggling.

What it means for journalists is that we are holding back information. We are trying to hold back the crap stuff. The average punter doesn’t mind if what they’re putting up is scraped or copied or taken from somewhere else. But as a journalist, you’re trying to find good stuff, and make sure that gets to the reader. To do this, we have to do what Thomas Crosby and all good journalists do, we have to get as close to the source as we can.

As a journalist, from a standing start, you are trying to understand a situation. How do you do that? How do you bring down the cacophonous and numerous voices you find on line to find out what’s going on?

‘Hurricane Sandy’ photoshopped

It can be difficult. Take Hurricane Sandy in New York. The perfect storm hit the iphone capital of the universe, and instantly a huge amount of copy, and a huge number of photos were being shared. One was a photo said to be of Sandy, but it was of a previous storm. This was a photoshopped tornado behind the Statue of Liberty that circulated on Twitter. Another was from The Day after Tomorrow, also claimed to be Hurricane Sandy!

We’ve seen some incredible fakes. One YouTube video we sat and watched for 15 minutes – horrible stuff – 2 guys seated against a wall, another guy in an army uniform comes up with a chain saw and takes one of their heads off. There was no doubt it was real, that a person was being beheaded. But it wasn’t from Syria, even though you could hear screaming in Arabic and the chainsaws whirring. Actually it was a video shot in 2004 in Mexico, overdubbed brilliantly, a truly professional job, beautiful propaganda from a functional perspective. But absolutely fake. We banged that through some translation searches, we found the word for ‘chainsaw’ in Arabic then searched on that word in multiple languages, searching for chainsaw videos, including in Spanish and that led us back to the Mexican video. There were multiple takes/uploads of it, and there was even a plasticine animation it was that old!

Another photo – real this time. Downtown Manhattan, the flooding during Sandy. This photo had a grilling online because all the journalists were so worried about fakes that they weren’t willing to say they could verify the photo without an incredible amount of due diligence on it. They thought it was fake because of technical details – the filter, how much light there is in the photo. But it was the work of Jesse and Greg, two well known New York bloggers and it was possible to stand it up fairly quickly.

Another photo – real this time. Downtown Manhattan, the flooding during Sandy. This photo had a grilling online because all the journalists were so worried about fakes that they weren’t willing to say they could verify the photo without an incredible amount of due diligence on it. They thought it was fake because of technical details – the filter, how much light there is in the photo. But it was the work of Jesse and Greg, two well known New York bloggers and it was possible to stand it up fairly quickly.

Two ends of the spectrum – the fake that looks real, and the real that looks fake.

But it’s not easy. For example in the Egyptian revolution, we monitored a twitter conversation that took place in Tahrir Square on the day Hosnei Mubarak decided to resign. In Storyful, we monitor lists of people on Twitter – by themes, by country, by region – so when something happens we can go to the relevant list and analyse it. We follow retweets, people joining a conversation, we watch for people retweeting the same tweet time and time again. We watch this via Tweetdeck and other tools and we can begin to get a picture of what’s being shared most, and as the conversation gets deeper. We can put it through Gephi, a free tool, and see graphically what tweets are getting most interest. Gephi is a visual representation analysis tool, a network analysis tool. Using Gephi you can literally see which people appear to have something interesting to say. Of course, at this stage, we are not sure it is valid, but they are the people we should investigate. This is the Gephi animation, put up by an Italian academic, Andre Panisson that enabled us to monitor that discussion in Tahrir Square.

Facebook is one of the best sources of information from Syria because there is a rich interconnect – lots of pages from local coordinating committees etc [these can be monitored in the same way as Twitter, you can see which stories gain traction among the protaganists].

So, you find someone or something you want to investigate. Take for example this video of a thunderbolt. It looks genuine, and if it is, TV stations and networks will want to run with it (ABC ended up using it 15 times on one morning show). The first thing we have to find out –is it new, is it recent, is it genuine or copied? This can be difficult to verify, if someone uploads something like this they may just be sharing it with a friend, sticking it up on YouTube for their granny to see, they are not thinking this will get on the news – [it could just be an old video they have come across].

We started our research. This video was on a YouTube account with just this one video. It had no identification except for the name – Rita Krill. We used a tool called Spokeo, a person finder tool (not freeware unless you are non-profit). There were several Rita Krills, including one in Naples, Florida. We then went to Wolfrom Alpha (an internet tool which lets you see weather reports from particular days) – the one that matched the day it was uploaded (rain, storms) was Naples Florida. So could we figure out if it was Rita Krill’s house in Naples Florida in the video? We went to Google maps and matched up the tells – the umbrella, the pool, the trees, the white lilo in the pool. This was the place! We called Rita, she gave us permission and the video ends up on the Ellen Degeneris show and gets 3.5 million views on YouTube! So there are lots of free tools to use.

But it gets heavier. Syria, Hama, 2012. A dozen bloody bodies in the back of a pick-up truck and the bodies are thrown off a bridge into the water below. This is a controversial video.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aOZJwMRAEJ0&bpctr=1377976845

It was alleged that this was Muslim Brotherhood throwing bodies of Syrian soldiers off the bridge, using blasphemous curses as they were doing it. We needed to check this out for a client, a lot of questions were being asked. Hama was under siege it was impossible to get in or out, but there were some people with internet connections tweeting from inside Hama, posting on Facebook and some were on Skype – we were able to go back and forth and ask them questions. We had 3 different sources – but were they credible? This is where credibility comes in. One source said ‘that bridge doesn’t exist’. One said ‘that bridge exists, but it’s not in Hama’. The third said, ‘Yes, I recognise the bridge, it’s in Hama, but the water flowing under the bridge shouldn’t be there because the army blocked off the dam upstream and the river ran dry when this video was shown.’ We started looking at the video, most people are distracted by the gore, but we look around for clues – in this scene, for example, the shadows are thrown to the north, so the bridge must run east-west. Second, it has distinctive railings, and it’s a two lane highway, and in the background you can see distinctive black and white markings on the kerb. Then looking at the river, there is a concrete edge on the right hand side and you can see a cloud of blood which tells me the water flows south to north, and then the river narrows. So we found the dam, and used Google Maps to look at bridge after bridge, looking for characteristics that match. We found nothing. So we looked at satellite view, further out from Hama, and this bridge started to look interesting. You can see it is 2 lane, with black and white kerbing. We found photos on Google maps, and lo and behold there’s the distinctive railing. So we went back to our 3 sources – the third seemed most credible, their information starts to seem most useful and valuable to our client. In the end, we couldn’t validate this video to the point where we could say everything is certain, but we were able to link our client with the sources and say which was the most credible.

That is how we do this investigative journalism on video, and you can apply this to any video you can find. We found on e in Cairo during the revolution where a guy was uploading to facebook in real time at the same time as Al Jazeera were having their doors knowcked down by the army and they were being pulled off their balcony – he was literally one building over (we could tell from the angle) and was the only person with footage of the Qasr El-Aini battle – troops, protestors, teargas being thrown.

What’s interesting about this is that we have done it for free. The tools – Spokeo, Wolfram Alpha, Google Maps, Twitter, Tweetdeck, Facebook, Gephin – and the only ones we’ve paid for are Spokeo and Skype (to call people). They are all available to everyone and this is the huge revolution in journalism. News gathering tools are at your disposal and it’s cheaper and quicker. But there is no less a burden in what you have to investigate because you have to apply old journalism techniques to this new material, just in a slightly different way.

A colleague of mine, Gavin Sheridan – you might know his blog – spends all his spare time doing Freedom of Information (FOI) requests – he gets reams of boring data, and it drives the rest of us in the office nuts because it fills up the office. He puts the data onto spreadsheets and puts it online. It seems ridiculous and pointless BUT you get other people coming along and saying “I’ve noticed this……do you think this is an anomaly? This number is higher than this number, maybe you should look into this.” So Gavin investigates and that is how his stories come out. For example, Gav and his colleagues’ investigated Irish Parliamentary expenses – they collaborated online, asking FOIs and with a cascade of information brought about the resignation of a TD [member of parliament] – all done with Google, spreadsheets, Fusion tables. There are so many tools for this kind of work that there is really no excuse.

When it comes to situations like that in Syria – the argument is, often, that this is killing journalism and killing foreign correspondents. To a certain extent that’s right – after all, we were able to do the work on the Hama video in 20 minutes from an office cubicle in Dublin.

Bamboozer is the software of choice for people all over – It started in Egypt, Libya and now Syria. You can use it on a very basic phone. People can set up a web cam on their kitchen window and in my office cubicle in Dublin I can see the live stream from the war.

We’ve seen the quality of video skyrocket. Initially it was very grainy (you can’t complain, of course, you can’t say go out nad shoot in higher resolution) but we know that organisations like AVAAZ and advocacy groups are training citizen journalists in Syria, and a like this arming them with better cameras and telling them how to film stuff.

It’s the first time we’ve seen a war documented in real time – not like in Iraq and Afghanistan. But some of it is propaganda – all the way through the Syria conflict you’ve had questionable videos. We spoke to a moderate supporter of Assad who said he’d been ithere when people were trained how to shoot film in particular ways (eg shooting from behind so you don’t see faces, or shooting from multiple angles so it looks like different incidents , which can then be released over a period of time to look like more events – we can pick up on this and we can say, no this is from one incident three weeks ago. They’ve even claimed that there was an explosion, when it was actually a huy setting a pile of tyres alight a couple of streets over, and they’d mimic the screams etc, but we could tell by the colour of the smoke. We’ve seen Syrian army videos with fake blood and fake torture videos like the one from Mexico.

It’s been a complete revolution and what you’re now seeing in Gaza in the last couple of days – I’m sure some of you will have seen the reports – basically the Israeli army is live blogging what’s going on in Gaza and gamefying it, saying if you like this page and if you like the Israeli Defence Force page enough you’ll get to a certain level, and we’ll give you the recruitment officer badge.

All this is changing how we see all the media. You used to be able to look at Fox or CNN or Sky and think 99% is probably true. But now that so much is pulled from social media we have to do more work and the viewer has to be more discerning. Anyone can find this stuff, there is a growing depository on YouTube – indeed it is becoming the world’s most important depository of evidence. A few days ago there were videos posted of alleged executions of Syrian soldiers by Free Syrian Army guys and the UN and Amnesty turned to the likes of us to back this up. Because we’d seen so many fakes, so many propaganda videos, we had to be able to tell them this was a genuine atrocity.

That’s a big mind shift for organisations like that. They are looking to YouTube for potential evidence in War Crimes Tribunals! And it is an uncomfortable postion for YouTube who see themselves simply as a platform, but that is where the information is.

This is a big shift for journalism. You have people there, not trained journalists but they have a camera and a video phone and if they take footage it’s from where they’re standing, from their perspective – they are seeing what they want to see, they put themselves in that position. But that perspective is no less real because of who they are. They are seeing what a journalist might see if they were there with a camera – so what’s the difference? Because this person is a student protestor, does it make what their camera is capturing any different from what an objective BBC cameraman might capture standing in the same position? I don’t think so.

It comes down to the consumer and the editor and the producer – they have to interpret the footage. The footage is what’s been happening being captured on film, it’s objective (as long as it hasn’t been doctored or been subject to the propaganda techniques we were talking about earlier. As long as it can be backed up, it can be used. If it is better than what you have access to, why not use it?

5 years ago you’d have had to send a team of journalists putting themselves and others in danger, establishing contacts, building rapport – it would have come at great expense to the company. But now if you send a journalist to Syria armed with that information, they have a two week jump on where they might have started 5 years ago. That allows journalists to do better, it allows journalism to be more effective and allows journalists to tell the story in ways they haven’t been able to before.

YouTube videos, amateur videographers – are they killing journalism? Maybe, but if you can get to the source, verify the video and embed it in your report, and because all reporting now has to be digital, how much time can you save, how many words can you save by putting a video in your story and doing the analysis beyond the video? A huge amount.

I don’t think you’ll every be able to take the journalist out of the process. You can go so far with computers, tools, algorithms, but algorithms are simple sequences of binary – yes/no, black/white – rules. But truth is never black and white, it’s never yes or no. It’s fluid, it’s always emotional, it’s a value. The journalist is the person who identifies that value and presents it to the reader.

Subscribe with…