Transcript

This is the second in our two-part series on the UN’s new offensive mandate in the Democratic Republic of Congo in which SOAS’s Dr Phil Clark talks to Paul Brister from Pod Academy about some of the causes of the conflict in the Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, and some of the challenges facing the United Nation’s (UN) new Intervention Brigade that has recently deployed there. [You can find the first podcast in the series here]

This podcast looks at the implications of the UN in DRC and its new proactive and aggressive approach – for the DRC, the wider region and for peacekeeping and the UN itself. It also contains a postscript outlining some of the developments that have taken place since Paul spoke to Dr Clark.

First Paul Brister gives some background on peacekeeping…

Paul Brister: UN peacekeeping missions are normally authorised by UN Resolutions passed under Chapter 6 of the UN Charter, and are guided by three basic principles: consent of the parties; impartiality; and non-use of force except in self-defence and defence of the mandate. A UN peacekeeping force is thus deployed in a context where there is a peace to be kept. It often involves monitoring and enforcing a cease-fire agreed between two or more former combatants, who view the UN force as being neutral and impartial.

Of course events on the ground can change rapidly: cease-fires may be broken, consent can become withdrawn, peace keeping forces may be tempted to stray into peace enforcement. And in the past the UN Security Council has been to slow to react. The classic case is Rwanda in 1994. During the 100 days of mass-genocide, the commanders of the UN forces on the ground [United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR)] repeatedly made ardent requests for authorisation to use their Belgian troops to intervene. These demands were consistently rebuffed and their mandate was never beefed up. Instead the troops were forced to stand idly by and helplessly watch the butchering. The UN troops had found themselves with a weak peacekeeping mandate in a situation that urgently required peace enforcement and were thus useless.

Peace-enforcement operations are authorised under Chapter 7 of the UN Charter and have far more robust mandates, sanctioning armed intervention to impose a solution. They tend to take place in a context of conflict rather than peace – a situation that is preferred by one or more of the belligerents. Therefore, unlike with peacekeepers, peace-enforcers are not welcomed by at least one of the belligerents and are not regarded as neutral. The insertion of a peace-enforcement force can convince belligerents that compliance with an imposed peace is less painful to battling this force. Sometimes though, the conflicts have proved too deep-rooted and intransigent, and little more than a pause between rounds has ensued. In other cases the cycle of violence has been broken, providing the conditions necessary for a political process that paves the way to a lasting peace.

Usually the aim of peace-enforcement has been to bring belligerents to the negotiating table. The goal has not been military victory but facilitating a settlement. And peace-enforcement operations have generally been outsourced or sub-contracted to other organisations. Although, for example, the UN Protection Force in Bosnia (UNPROFOR) was authorised to use enforcement action, coercive action was in reality left to NATO, which had been sanctioned to undertake enforcement measures alongside the UN peacekeeping force. This culminated in the replacement of UNPROFOR by the more ‘muscular’ NATO-led force, IFOR. Although the NATO-led operation rested notionally in the hands of the Security Council, in real terms NATO leaders, not the UN, called the shots.

Historically, it has generally been the case that the more aggressive the UN mandate for military action has been, the less control the UN has had over of it. This has been due to an understandable unwillingness on the part of those states partaking in these more aggressive enforcement actions to submit their forces to the bungling command and potentially enervating scrutiny of the UN. This is especially so in the case of the US, which is eager to attain UN authorisation to legitimise its military operations, whilst unwilling for UN command and control to be placed over them. Pursuant to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in August 1990, a UN Resolution (678) endorsed its hitherto most potent and wide-ranging enforcement action. Although the US multinational coalition was described as having been ‘subcontracted’ to act on behalf of the UN, it was not responsible to the UN, as was reflected by the absence of UN symbols and flags used during the campaign.

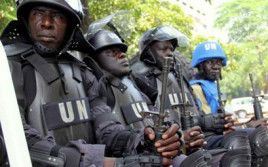

For the last 65 years then, the work of the blue helmets – the discernible agents of the UN – has largely been restricted to peacekeeping operations such as conflict prevention, civilian protection, inserting a buffer between factions, and post-conflict stabilisation. Normally they have sought to help create the space that can make possible the reaching of a settlement. Now all that is set to change.

Until recently, MONUSCO’s functions were restricted to protecting civilians and affording support to the DRC’s army (FARDC). Although it was permitted to use force to fulfil its responsibilities, it routinely showed itself inept at reacting to rebel aggression, and in November last year its troops stood by and watched as M23 rebels captured North Kivu Province’s capital Goma. Stung by heavy criticism, the UN has lost patience and appears to be putting its penchant for neutrality to one side. Now it intends to annihilate the M23 – a particularly vile faction in the conflict – and it seems prepared to role up its sleeves and do the dirty work itself.

While many have been quick to applaud the long awaited arrival of a UN force with teeth, others have cautioned against this move into potentially hazardous waters. For these critics the UN has already seriously weakened its claim to adhere to the principle of strict impartiality – the philosophical foundation of peacekeeping – since it begun conducting joint operations with the FARDC in 2005. Now, with the deployment of an aggressive UN force with the task of neutralizing armed groups, it appears to many that this principle has been utterly rejected.

Furthermore, many argue it undermines the peace efforts of the 11 African countries of the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region that brokered the Kampala peace talks – these talks broke down in April. It also undercuts the progress represented by the signing of the Peace, Security and Cooperation (PSC) Framework Agreement signed in February (2013). The agreement calls for political reforms in Kinshasa and was described by UN special envoy Mary Robinson as a “Framework For Hope”. Not only does the brigade’s aggressive mandate seem to fly in the face of Ms Robinson’s pleas for dialogue, but many now fear that this will allow the Kinshasa government to renege on its commitments to reform – and its subsequent actions seem to bear out these fears.

Even if the UN Intervention Brigade turns out to be a game changer, this military solution does not address the underlying social and political problems to this crisis. UN Security Council Resolution 2098 acknowledges this in its preamble, urging “the Government of the DRC to remain fully committed to the implementation of the PSC Framework…”

Dr Clark, the mandate for the new Intervention Brigade does rather seem to clash with the objectives of the Kampala peace talks, designed to find a peaceful settlement to the M23 rebellion, doesn’t it?

Phil Clark: I think there are two key problems here. One is that the Intervention Brigade at best is a Band-Aid measure. It may remove some key rebel elements from the conflict, although I have my doubt about how effective it can be in that regard. But let’s say hypothetically that this Intervention Brigade is able to dismantle both the M23 and the FDLR rebel operations – and that would be seen as a remarkable success. But it’s not as though Congo’s ills are going to be cured overnight by removing these rebel groups. There’s much deeper political work that has to be done. And in essence, what that means is completely reforming the way that Congolese politics is constructed. It means bolstering the Congolese state. It means building effective institutions. It means putting in place a government in Kinshasa that does in fact have the interests of its own citizens at heart and that has the ability to exert authority from Kinshasa, 2000km away in the west, into these very volatile parts of eastern Congo. And that’s going to take a much slower and more systematic political campaign of reform than can possibly be encapsulated by the Intervention Brigade.

So I think the first problem is that this Brigade is only ever really going to be at best a piecemeal response to much deeper political problems. The second issue also is that this Brigade is in many ways incoherent with other international strategies to try to bring peace and stability to eastern Congo. And at the moment, one of the biggest elements of that international push is through the Kampala peace talks, which have stalled on various occasions over the last six or seven months, but these are talks between the regional governments and the M23 rebel leadership to try and find a political solution to the conflict. And for many of those months, the UN and other international bodies saw the Kampala talks as the best way of achieving peace in eastern Congo. There was an enormous amount of fanfare – an enormous amount of time and energy poured into these talks.

M23, Rwanda, and other parties in the region I think quite rightly now say: “how can we proceed down the pathway of negotiations at the same time as the UN is putting this intervention force on the ground with a mandate to target the same rebel groups that are also being asked to talk peace in Kampala?” And I think there is justifiable concern about a fundamentally incoherent message that the UN and other international actors is spreading. We’re willing to use the barrel of the gun in eastern Congo but we’re also hoping that the parties will talk peace in Kampala. Now if you ask the UN leadership about this approach, they will say: “look, in fact it’s not incoherent. This is two sides of the same coin. It’s a carrot and stick approach. What we’re trying to do is compel M23 to negotiate in Kampala by threatening them with military force in eastern Congo. If we can weaken the rebel force militarily then it will make them more compliant and it will make them more willing to engage in peace negotiations in Kampala.”

My sense is that sounds very good rhetorically but it doesn’t match the reality on the ground. And I think what we’re seeing at the moment is an M23 that recognises that it’s about to have a serious military fight on its hands with the Intervention Brigade, and it has stopped talking about the peace negotiations in Kampala. It in essence has said: “we don’t buy the deal that the UN is putting in front of us. We don’t believe that the international community is serious about peace. All we hear are the threats of this Intervention Brigade and all we hear are the threats of military attack.” And so the M23 has spent the last few months not seeking political negotiations in Kampala, but instead gearing itself up for a very serious fight. And I think in this sense we’ve seen any attempt at peace negotiations fall apart and the parties are preparing themselves to go back to war.

P.B.: Before Resolution 2098 was passed, when M23 seemed to have a distinct military advantage on the ground in some parts of North Kivu province, the government did indeed seem prepared to negotiate with the rebel group. But now, with a UN Intervention Brigade behind it and the military balance once again tipped in its favour, the Kinshasa government has called on the auto-dissolution of M23, thus rescinding on the Kampala peace talks. It appears that all along the Kinshasa government was simply buying time and was never serious about addressing ethnic concerns or reaching any political accommodation.This resolution has rather let the Kinshasa government off the hook and allowed it to avoid engaging with the different parties in search of a lasting settlement, hasn’t it?

P.C.: Yes, to a large extent I would agree with that. I think one key impact of the Intervention Brigade entering this conflict is that it has moved any serious incentive for the Kinshasa government to take part in the peace talks. Now we need to be honest about how those peace talks were going, and it’s true that those talks had stalled on numerous occasions. Both M23 and the Congolese government were responsible for the stalling of those talks at various junctures. At various points it was legitimate to ask whether anyone was really serious about this process. But by the same token, there were moments of breakthrough, and there were important political issues that were being discussed in Kampala. And my sense was that there needed to be another strong, dedicated push to try and get a political process – to try and find a political solution to this conflict – rather than rushing back to the battlefield and trying to seek a military solution.

P.B.: Proponents of offensive operations will argue that security is the underlying condition for any meaningful development and that the rebels are quite happy to use force and wreak havoc when they are able to. They understand only the logic of might. Objections about commitments to a peace process are coming from a force on the back foot. This is testament to the threat that the new UN Intervention Brigade poses to them.

P.C.: I don’t think that’s the case because the Kampala talks were never tried in all seriousness. There was a reluctance on the part of both M23 and the Congolese government to negotiate in good faith in Kampala. That was one of the key reasons why those talks struggled so much over that lengthy period. But also the international community was very uncertain whether it wanted to engage in these peace talks. It had a rapidly evolving situation on the ground in eastern Congo. You had an international community that was still trying to get its head around what effective peacekeeping in eastern Congo would look like. And so this Intervention Brigade was to a large extent a knee-jerk reaction. It came out of a period of real uncertainty and a real lack of clarity in international thinking. And so I think that the problem at the moment is that we have the UN resorting to massive force to try to resolve this conflict in eastern Congo before a peace negotiation process has actually seriously been tried. And I think that the danger again is that we’re going to see an escalation of violence and very little scope for peace negotiations any time soon.

P.B. For all the talk of multi-dimensional peacekeeping, the mandate for the new Intervention Brigade also rather seems to clash with the mandate for the rest of MONUSCO doesn’t it?

I would agree. I think what the UN is doing in mandating the Intervention Brigade to actively target rebel groups is throwing away any attempt at the much deeper political and social work that the original UN peacekeeping missions had in eastern Congo. You can argue that MONUC and then MONUSCO failed to live up to their mandates, but their mandates, in many ways, on paper I think were quite effective. They said that, yes there would have to be a military approach taken to protect civilians, but that peace and stability in the long term weren’t going to come to Congo unless there was serious political reform. I think the message that’s being sent with this new Intervention Brigade is that that reform doesn’t need to happen, that those deeper reform issues are completely off the agenda and that, provided M23 and FDLR and these other groups can be removed from the terrain, then peace and stability are somehow miraculously going to come to eastern Congo. So I think the danger here is that not only that the Intervention Brigade’s mandate clashes with that of MONUSCO – and you have this absurd situation now of two UN peacekeeping operations effectively operating side by side in the same country – but you have an Intervention Brigade that has moved away from this idea that peace and stability only come through politics. And I think that’s a really important message that we have to emphasise: that if we’re serious about long-term peace and stability in eastern Congo, it can only come through political reform. It can only come through a dedicated process of building stronger institutions; developing more effective leadership; of building a coherent Congolese state. And all of that requires longer and slower processes than simply trying to attack these rebel movements. And I think it’s that longer-term agenda that we’re not seeing being spelt out systematically by the UN at the moment.

P.B.: Many NGOs have warned that offensive action could cause a humanitarian crisis. Do you think there is a danger of this?

P.C.: I think there’s a serious danger of this, and I think the NGOs on the ground are right to be very worried about what this Intervention Brigade might bring in terms of a humanitarian crisis and in terms of complicating their work. And many international NGOs, about five or six weeks ago, signed a petition to the UN Secretary General saying that they were worried about the humanitarian consequences of increased force in eastern Congo. And this comes from groups that have longstanding engagement in this part of Congo. These are groups that have been working there for ten or 15 years and undoubtedly they remember what Congo looked like in the late ‘90s and the early 2000s when violence escalated, when regional actors got involved. The actors that suffered the most out of this situation undoubtedly were the Congolese people themselves and I think there’s very legitimate concern that we might see something similar happen all over again

P.B.: Interventionists will say: “yes, in the short term, suffering of the civilian population may increase. But this is not a reason that justifies doing nothing and allowing the rebels to continue to hold sway.” But you seem to think that there are some very serious dangers associated with the introduction of the Intervention Brigade into eastern Congo and the risk that regional actors will be drawn in?

I think the danger with the military solution is that firstly it does distract the Congolese government from a serious reform process. But also the danger is that it will escalate this conflict. It won’t, I think, just escalate the conflict on the ground. But it also risks regionalising this conflict by sucking in countries – like South Africa, like Tanzania, like Malawi – and taking us back to a situation that we saw in eastern Congo ten years ago, which was that this simply became a battleground for a range of other countries in the region to try to pursue their own military and political and economic interests. I think the danger of this Intervention Brigade is precisely that: that we may once again see a regional conflict on a grand scale in this part of Congo.

P.B.: Although a number of rebel groups are named in Resolution 2098, the 23 March Movement – currently DRC’s greatest rebel menace – does seem to be the clear focus of the Intervention Brigade. Focusing singularly on M23 would seem then to put MONUSCO in a politicised position vis-à-vis other rebel groups – and in so doing gives some not inconsiderable justification to the claims of those who argue that the UN force is increasingly becoming a party to the conflict and forfeiting any moral position of impartiality it may have once have claimed.

On 15 July, Rwanda’s ambassador to the UN went as far as blaming the Brigade of jeopardising regional peace efforts by ‘picking sides’ among the armed groups and discussing ‘strategic collaboration’ with the Hutu rebel group FDLR and the Congolese army. To what extent do you think the Rwandan ambassador’s fears are justified?

I think right from the beginning of the UN’s involvement in eastern Congo there have been legitimate questions about the politicisation of the peacekeeping mission. The selection of which groups the new Intervention Group goes after of course is a key political question. And if the Brigade only goes after M23, it will open the UN up to the accusation that it’s become highly politicised, and that it’s only targeting particular groups, it’s only targeting particular interests, and it’s leaving completely untouched a range of other rebels and a range of other agendas.

And as I said at the start, one of the issues that the UN faces in Congo and that I don’t think the UN has yet got its head around, is what do you do when you are mandated to support a government – and you can only operate on the ground at the behest of that government – when it’s that very government that is targeting its own civilians, that is committing crimes, and that ultimately is part of the problem. That has been a problem for the UN right from the very start of its peacekeeping operations in eastern Congo

P.B.: After being routed from Goma last November, Congolese government troops caused havoc in the surrounding countryside, raping and looting profusely. So many local people in the area are, quite understandably, just as afraid of and bitter towards government forces as they are of the rebels. And now the UN may conduct joint operations with these same fighters.

Do you think that the UN is running the risk of creating a politicised force with an offensive mandate that could come to be seen as a kind of occupation force? And do you foresee this having such negative effects as pushing some into the arms of militias, increasing local resistance and indeed exposing humanitarian staff to new risks?

P.C.: So we’re talking about a Congolese government that has targeted its own civilians through various means. It has often done so directly through the Congolese army, the FARDC. But it has also done so through proxies, including Mai Mai militia, the FDLR rebel group and other groups at various stages of the last decade. And the UN at various stages of this conflict has been guilty of actively supporting the Congolese state as it has committed these crimes against its own citizens. So that is an issue that the UN still has not come to terms with. And it’s interesting in the context of the current Intervention Brigade that the UN always refers to the need for neutral arbiters – the need for impartial actors – to help bring this conflict to an end. But the UN has never been neutral in this conflict and it’s certainly not seen as neutral from the vantage point of the local population. If anything, the UN from day one has been seen as part of the conflict because it continues to support this government that is responsible for very serious crimes. Now those concerns take on an even greater dimension in the form of this new Intervention Brigade, because now we see the UN actively getting involved in hostilities and in essence having to take sides – having to say, “we are going to target these particular rebel groups to the exclusion of other rebel groups.” And what that inherently means is the UN is choosing which political and military interests it believes it can support, and as a consequence it’s getting drawn even more into the conflict. And so I think that raises some really important questions about the legitimacy of the UN as a peacekeeping actor and what kind of impact that’s going to have on the ground when you have the UN effectively taking sides in the way that it is at the moment. And let’s be honest, taking sides in a conflict like this means always backing an organisation with blood on its hands. That unfortunately is the reality of this conflict and that’s the problem that the UN is confronted with in this conflict.

P.B.: What approach do you think the brigade will take towards the pro-government militias?

P.C.: It’s difficult to tell, but my guess is that the Intervention Brigade will only target M23. From day one I’ve never believed that the Brigade was capable of fighting multiple rebel groups simultaneously. As I’ve said, this is a brigade that is new to this terrain – it’s having to learn as it goes. It’s taken a longer time than many people expected for the Brigade even to get onto the ground and to get organised enough for it to launch it’s operations. I think the Brigade will focus solely on M23, and we have to be really sober I think about what that means.

That means that we will see the UN targeting M23 for a very, very long time. This is not going to be a clean and a quick fight. The way that many UN officials talk about the Intervention Brigade you would think that this is a fight that will be over in one or two weeks – that somehow peace will be achieved in the Kivus as a result of that. That’s just completely fanciful. It will be a long conflict. It will drag on. There will be a large civilian death toll as a result. It will undoubtedly result in the large-scale displacement of the population. And that’s just in the context of tackling M23. I wouldn’t be surprised if targeting M23 in essence takes up the entire time mandate of this Intervention Brigade, and they discover that the mandate then has expired and that then they’re going to have to extract themselves from Congo. So I think we need to be honest and clear that ultimately this is a brigade that has been designed to deal with M23 and M23 alone.

P.B.: Do you think that the UN could become embroiled in a conflict which is costly – both in terms of money and human life – and for which its members do not have the stomach?

P.C.: Yes, I think the Intervention Brigade is going to test the resolve of the UN as an organisation, but also test the resolve of the three countries that will be sending their forces to join the Brigade. I think the message that’s being sent to the South African, Tanzanian [and] Malawian populations at the moment is: “don’t worry about this brigade, this is a short term measure, it’ll be forensic, it’ll be incisive, it’ll get in, it’ll do the job, it’ll dismantle these rebel organisations, and then will be able to get out. And I don’t think anything of the sort is going to happen.

And I think there are real concerns in the region about what happens if the death toll starts to rise. And some Rwandan officials have even said: “look, given that Rwanda has been so heavily linked with M23, what kind of diplomatic fallout will there be if M23 rebels kill South African, or Tanzanian, or Malawian peacekeepers?” That will be seen as a huge regional issue, and there will be undoubtedly an outcry in South Africa, Tanzania or Malawi if M23 rebels commit those kinds of acts. So the concern here is that the political temperature in the region is being raised. That it’s not just about a conflict in eastern Congo: this is also about the solidity and the relationships of an entire southern and eastern region of Africa, and those concerns I think will only be compounded as the conflict undoubtedly takes a very very long time. So I think these concerns are very real.

P.B.: What chances do you give the Intervention Brigade of success?

P.C.: In the way that the Intervention Brigade’s mandate is written at the moment I give it very little chance of success, particularly in terms of its claim that it will tackle a range of rebel groups. I don’t see it being capable of doing that. As I said before, I think the Brigade will target M23 only, and in only targeting one rebel group it will have failed on its own terms, because its mandate dictates that it has to take a broader based approach than that. I don’t think it will do anything of the sort.

And even on that discrete objective of targeting M23, I think the Brigade will face significant challenges. And I think the higher-ranking officials within the Brigade recognise this. I think perhaps they’re a little more sober about the challenges ahead than some of their political masters might be. I think there’s a recognition within the Brigade that M23 will be a formidable opponent for all of the strategic advantages that I’ve talked about before. And so it remains to be seen, even in targeting that single rebel group, the M23, whether the Brigade in fact can be successful.

P.B.: What would be the risks for the UN if it failed with this experiment?

P.C.: I think there are both short-term and long-term risks for the UN. I think the short-term risks relate to many of the thing I’ve already talked about: a risk of escalating the conflict on the ground; a risk of regionalising the conflict; and ultimately leading to a humanitarian crisis. But I think in the longer-term, the risk for the UN is that it’s simply going to run out of ideas of how to deal with the kinds of conflicts that we’re seeing in eastern Congo at the moment. Because, let’s face it, Congo isn’t alone in engaging in these very complex ongoing conflicts that the UN is now becoming embroiled in. We’re seeing very similar types of dynamics in other places around the world. And Syria of course would be an example that springs to mind.

I think there’s a real need for a deeper reckoning with the challenges of ongoing violence on a large scale and also the challenges of conflicts that don’t fit the national picture that the UN has often had. And in Congo one of the challenges for the UN is it’s not as simple as supporting a national government, targeting its rebel enemies and trying to bring peace and stability in that kind of way. Because as we know all too well, the conflict in Congo has multiple causes and it’s more complex than that. And so peacekeeping and peace-building in the future is going to have to deal with deeper levels. It’s going to have to penetrate below that national level to say: “can we deal with things like land issues, ethnicity, population movements, mass migration, all these other elements that have ultimately fuelled violence in Eastern Congo? Can the UN meaningfully get involved in those kinds of issues and resolve conflict at those levels, so we don’t see a perpetuation of violence into the future?” So I think that the risk for the UN, if the Intervention Brigade fails, is that it’s going to have to go back to the drawing board and that it’s going to be shown up as a largely confused and disorganised body that many African populations are increasingly losing faith in when it comes to solving large scale conflicts of these kinds.

P.B.: Article 9 of Resolution 2098 states that the measures to be implemented, which include the creation of an Intervention Brigade, are “on an exceptional basis and without creating a precedent or any prejudice to the agreed principles of peacekeeping”

Surely nobody really believes this? If this change in tactics is successful in establishing some measure of stability in eastern DRC, this will undoubtedly change the way the UN thinks about peacekeeping.

I suspect that you would not be in agreement that it is time that a previously risk-averse UN became more bullish

.P.C.: I think that we have to be very careful about a more bullish UN. I think it’s more important that the UN becomes better informed and better educated about how conflict is actually happening around the world. I think rather than charging in and attempting these full-frontal military assaults and hoping that peace and stability comes through that avenue, it would be better for the UN to sit down and really grapple with the complexities of violence. I think at the moment, Congo is almost a laboratory for UN peacekeeping, and I think the new Intervention Brigade is simply the latest experiment. I think it’s an attempt to try and find a way to deal with ongoing violence on a massive scale. And my sense is that in the long term it is an experiment that is almost bound to fail.

I think what the UN has to do is stop and pause, and rather than charging ahead, think deeply about how it can effectively deal with violence on this scale. And I think that would involve a really serious stocktaking exercise about what it has done wrong in Congo in the last ten years. Because, let’s be honest, UN peacekeeping has failed on a massive, massive front: civilians have not been protected; stability has not been achieved; the authority of the Congolese state has not been increased; the UN has categorically failed. And it’s failed in Congo – very soon after it failed in Rwanda – so there’s clearly something wrong here.

And I think that ultimately what’s wrong is the UN has a flawed understanding of violence that informs the way that it goes about peacekeeping. It has an idea of conflict that doesn’t fit the way that violence actually plays out in Africa. And I think the model that the UN operates on is one in which you have a state which has to be protected and bolstered and that is under threat from a range of actors. And if that range of threatening actors can be reduced, then it will allow the authoritative state to flourish.

But violence at the moment in many parts of the world, but perhaps most starkly in Congo, is operating very, very differently from that. The state itself is often complicit in major crimes [and] conflict is often being generated at the local and the provincial levels as much as it is at the national level, and so effective peacekeeping has to be able to capture that complexity and respond to it systematically. And until the UN starts to do that deeper thinking, and it starts to tailor its operations to the specificity of places like Congo, rather than trying to adopt this ‘one size fits all’ approach, which is what we continue to see in international approaches, then we’re going to see the UN continue to fail. I think the problem for me at the moment is I don’t see the UN being that willing to do that tougher thinking and to tailor its approaches to specific situations like the one we find in the DRC.

P.B.: How far away do you think we are from seeing a UN Rapid Reaction Force and do you think that this could be part of the solution?

P.C.: I think we’re a very long way away from that kind of reaction force. This is something that has been talked about for a very long time. I don’t see any serious political momentum behind it. And even if the force existed, it wouldn’t solve this fundamental problem of needing to deal with modern violence on its own terms. And so at the moment I think that the issue with UN peacekeeping isn’t so much a question of: how many troops does it have at its fingertips? Can those forces be mobilised quickly? It’s a deeper philosophical problem of: do we understand violence and what actually triggers it? Do we understand the causes of conflict and then can we formulate effective peacekeeping responses to those very particular forms of violence? That I think is a more fundamental question that even something like a rapid reaction force is simply not going to deal with.

P.B.: How do you think the UN’s experience in the DRC will affect the way the UN thinks about peacekeeping operations going forward? What are the potential opportunities of this new approach to peace enforcement? And what are the inherent risks that the UN runs by setting this precedent with the Intervention Brigade?

P.C.: I think the risk it runs is that even if this Brigade has a modicum of success – and let’s be honest, the UN is desperate to send a message that the Brigade will be a success, so even any lessening of M23’s capacities will lead the UN to proclaim that the Intervention Brigade is a success. If it does that, then the risk is that the UN will be pressured to do similarly in other conflicts around the world – that other situations will be encouraged to say: “look, you sent in this Intervention Brigade to Congo with a robust mandate. You allowed it to tackle belligerence directly. Why aren’t you doing the same thing here? Why aren’t you doing the same thing in Syria? Why aren’t you doing the same thing in Afghanistan? Why aren’t you doing the same thing in Columbia? Why aren’t you doing the same thing in various parts of the Indonesian archipelago?” This will become the refrain, and it will be serious refrain. There will be serious political pressure in other parts of the world for the UN to adopt the same strategy that it’s doing here. So the UN is trying to say that this will be a discrete, contained brigade and that it’s not setting a precedent. But the genie will be out of the bottle and it will be possible for other actors around the world to say: “we want to see the same kind of interventionist approach taken here”. And I think that would be a very dangerous precedent to set.

P.B. Well I don’t think there is anyone who would seriously suggest that the UN could, in its present form, hope to tackle all that. But the organisation has come in for some very serious flack in the past for failing to protect civilians through inexcusable procrastination and inaction – perhaps most notably in Rwanda in 1994. So there are those for whom a more proactive approach from the UN will be a very welcome response to its earlier failures.

PC: Undoubtedly this is a tacit admission by the UN that it has failed in the past. And not just failed as long ago as 1994 in Rwanda – but failed much more recently in terms of peacekeeping in Congo. I mean that, to my mind, is a very important lesson that we need to derive from this Intervention Brigade. It’s a lesson that the old way of doing peacekeeping has not worked. It has failed miserably in this part of Congo. The problem for me is I don’t think the new Intervention Brigade is the answer to that problem. I don’t think the answer is to give a more robust militaristic mandate to the Brigade and ask it to target specific rebel groups. I think the danger there again is that it will politicise the conflict, it will regionalise the conflict, and it may simply escalate violence in the long term, and it will distract us from more important political reforms.

P.B.: So you’re damned if you do and you’re damned if you don’t?

P.C.: To some extent: yes. But I think in this case the UN would’ve been better off simply saying: MONUC and MONUSCO have failed. What we need to do is take our time; go away; reform the mandate of the peacekeeping mission; put a greater emphasis on political negotiation, institutional reform, the building of a robust Congolese state – rather than a knee-jerk, Band-Aid approach which in essence is what the UN is taking with this Intervention Brigade. In essence it’s saying: “we think there’s a quick fix. We can fix this conflict if we simply eliminate one and possibly two major rebel groups.” And again, I think that’s getting us away from the kind of deeper, slower reform process that ultimately is going to be necessary in this context.

Postscript

The interviews with Dr Clark were recorded on 20 August during a relative lull in the hostilities. In the intervening time, a number of the issues that he highlighted have manifested themselves. Notably, the International Brigade has targeted first and foremost the M23, while the Kinshasa government seems increasingly to be paying only lip service to the peace talks, and regional tensions have been escalating.

In fact, the day after I spoke with Phil Clark, fighting flared up again between the UN-backed Congolese forces and the M23 rebels. According to UN troops this was initiated by the rebels who, we may surmise, were frustrated by the lack of any real progress with the peace talks, and were fretting as the Intervention Brigade nears full operationalization and UN drones will soon begin patrolling the skies. It seems therefore that the M23 command may have miscalculated that ramping up the pressure on Goma might have succeeded in forcing a compromise in Kampala.

As the fighting unfolded, UN forces shelled rebel positions in the Kibati heights to the north of Goma, and the rebels allegedly responded by firing mortars at Goma, killing five civilians. Both the Congolese and the rebel forces sustained heavy casualties, but on the eighth day the UN deployed heavy artillery and MI-24P helicopter gunships in support of a government offensive, decisively tipping the balance in the favour of the FARDC. In that day alone, the UN helicopters – which have proved pivotal in a number of recent African battles – are said to have fired 216 rockets and 42 flares at the M23 positions. Two days later the M23 group announced that it was withdrawing its troops towards Kimbumba to the north.

Both the Congolese and UN forces have hailed this as an important breakthrough against the rebels. Exultant South African commanders bragged about sniping down six rebels and claimed that they had sent a message to the rebels that Goma is henceforth off-limits. Meanwhile, for the FARDC, this represented their most significant victory in eighteen months of conflict, and bullish Congolese army spokesman, Lt Colonel Olivier Hamuli, proclaimed that his forces would pursue the M23 rebels and recapture all of their territory. And, according to sources close to the Kinshasa government, buoyed by this recent military success, President Kabila has all but concluded that negotiations can be dispensed with and that military victory is within grasp.

But the situation in eastern Congo is never so clean cut. Certainly, the out-gunned M23’s retreat northwards is a strategic setback for them – no longer able to strike directly at Goma, the rebels have lost leverage in any negotiations for a settlement. Yet the rebels have proved remarkably resilient and adept at adapting their tactics. In another development, for some weeks now, there has been a constant stream of Congolese refugees into the Kimbumba area. By some estimates they now number over 3,000, and although the majority of these returnees from the Rwandan refugee camps are Congolese Tutsis, most of them are most likely not from this area at all, but from Masisi. Kimbumba now lies at the southern extremity of M23 territory and therefore constitutes the new frontline in the conflict. And it has been suggested that the fact the M23 rebels are welcoming them to settle in close proximity to their positions is a cynical yet expedient ploy to furnish themselves with a human shield. This would make engaging many of the rebel positions with attack helicopters problematic, thus neutralising the UN’s decisive tactical edge.

Furthermore, the Congolese military cannot take for granted UN support. In the weeks following the fighting at Kibati, UN Special Envoy Mary Robinson has repeatedly called for a pivot from military to political processes and resumption of negotiations. But apparently non-negotiable arrest warrants for many top M23 commanders, combined with intransigence in Kinshasa, represent significant barriers to progress here – on 21 October both sides announced a halt in the Kampala peace talks. Moreover, the FARDC has shown signs that it now feels emboldened to go it alone – only a week earlier [15 October] it had attacked M23 rebel positions near Kimbumba supported by FDLR rebels.

This flagrant collaboration with the Rwandan Hutu rebel movement is likely to further enrage the DRC’s small but militarily potent neighbour Rwanda, which was already fuming after a Rwandan woman was killed in cross-border shelling during the fighting in late August. Both the FARDC and M23 accused the other of being responsible, but Rwanda holds the former accountable. At the time, Rwanda’s Deputy Permanent Representative to the UN in New York, Olivier Nduhungirehe, reacted furiously, declaring that a red line had been crossed. These Rwandan criticisms of the Congolese army are more stinging even than any that it has made during previous incursions into its neighbour’s territory. Rwandan media published photos of armour moving towards the Congolese border where Rwandan military forces were amassing, and a number of world leaders hastened to urge restraint on Kigali.

So, for the time being, the M23 rebels have been pushed onto the back foot, but they are by no means a vanquished force. Even if the Congolese military manages to maintain its momentum and succeeds in routing its foes in the M23, conflict in this region is likely to persist in cyclical bouts for as long as underlying grievances remain unaddressed. The prospects for the much bigger and longer-term tasks of top-to-bottom reform of the FARDC and the implementation of a genuine national reconciliation programme remain bleak and a peaceful resolution elusive.

A knowledgeable, interesting and stimulating exploration of the background and current situation in the DRC.