Transcript

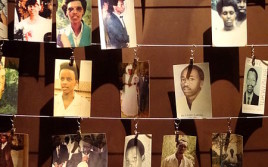

July marks 20 years since the end of the Rwandan genocide. In the summer of 1994 the death of the country’s president, Juvenal Habyarimana, sparked brutal violence between the country’s two major ethnic groups. The genocide took place over a hundred days, but left an estimated one million people dead.

This is the first of a series of three podcasts in which, Rwandan academic and genocide survivor Dr Richard Benda, talks to Alex Burd about the process of reconciliation and the country’s charismatic leader, President Paul Kagame, as well as his own memories of the genocide.

Richard Benda’s research at Manchester University addresses key questions in relation to religious authority and the role of faith in response to the complexity of African identity-based conflicts, of which the Rwandan genocide is an extreme case. In this podcast he explores the role of religion, and the role of the state, in Rwanda’s healing process.

Richard Benda: After the genocide, there were debates as to which faith community handled the genocide better. Some said Muslims behaved more rightly than Christians, but I find the difference between the Muslim and Christian response is that the Muslims responded as a group whereas Christians reacted as individuals.

But after the genocide both groups were interested in developing a reconciliation framework which takes faith seriously or which accepts that faith has capital that can contribute greatly to reconciliation. So they came together, the initiative was chaired by the Mufti of Rwanda and the Rwandan Archbishop Emanuel Kolini. The idea was to provide a platform where faith can contribute to building the country after the genocide because they recognised that they did little before the genocide and during the genocide, well, not as much as was expected, anyway.

The interfaith programme is still going on. It started with work in prison, with prisoners, people who had been convicted of genocide, getting them ready to face their moral responsibility, to confess – the emphasis was on repentance, confession, and facing criminal responsibility with a clear conscience (as much as possible).

Alex Burd: Is this about forgiving themselves?

RB: Yes, and it is very important. Theologically it’s another understanding of justice when you deal with people who have been involved in acts of violence, acts of evil as you’d say in religious language. You want them to face their responsibilities. First and foremost you want them to discover themselves as humans and the path to doing that is accepting themselves as still God’s children. Christians believe God’s grace is already there and God forgives. The problem Is knowing if they can forgive themselves. So you’re right, it is getting them to accept their own selves, forgive themselves and take steps to ask forgiveness of others. The first step must be the person – if they aren’t reconciled with themselves it becomes very difficult to be reconciled with others.

It is not as if the people involved in Inter Faith came to the perpetrators first – some perpetrators longed for that experience, that cleansing.

AB: That spiritual guidance…..

RB : Yes, it’s almost a pastoral care exercise, but also a political exercise.

AB: How do you mean, a political exercise?

RB: You don’t preach or help them to find their way back just in church, you also want them to become better citizens, to reintegrate into the wider political community because after prison they will have to go out and live back in their villages, in their towns and you can’t just cater for their souls. They will have to go about community activities, vote, so yes there is a political aspect. And political too, in that the government encouraged the pastoral care, supported it, gave access to prisoners. So there is a mutuality between religious leaders helping the state and vice versa.

AB: Can you explain the religious demographics in Rwanda?

RB: Statistics are treacherous in the context of Rwanda, but Christianity is dominant. There were discourses after the genocide saying that because Muslims seemed to have given a good account of themselves during the massacres, that Islam grew phenomenally after the genocide- that people in droves were converting to Islam. But that was media sensationalism. From what I gather Christianity still represents 95% and Islam is somewhere around 4.5%. Islam grew slightly after the genocide but I read that the Mufti of Rwanda said growth in Islam stabilised in 2002.

I can’t tell between Catholics and Protestants. I strongly suspect that Protestantism grew after the genocide. I’d probably hazard a guess at a 45% Protestant and 55% Catholic divide.

AB: The Belgian and French influences?

RB: Catholicism had been very dominant from the beginning of the 20th Century until 1990. Around 1990/91 with the revival in the Pentecostal church, more and more people began to leave the Catholic church, to convert to Protestantism. In fact they converted to Pentecostalism in the same period and quite a few people did the same thing after the genocide when new churches were set up and most of them were predominantly Protestant. The French and Belgian influence was there from the ‘White Fathers’ and from the Belgian colonial administration.

AB: What status does the Christian church enjoy in Rwanda? Particularly the Catholic church came in for a lot of criticism for its lack of action in 1994 – ranging from lack of action or complicity in the violence.

RB: There are three ways of looking at the Catholic church situation in Rwanda. From the outside it is viewed as an institution that has been compromised for quite some time because of its history and its interaction with the state. It took a serious battering in, and after, the genocide. It is a very bruised church. But there is more introspection going on than probably transpires in public. I still think the Catholic church needs to come out and make a public assessment of what really happened in 1994, and how the church is carrying on after 1994.

But even after the tragedy, the churches are still full. Most of the churches that were destroyed have been rebuilt and congregations are still as vibrant as they were.

I don’t know if that is a good or a bad thing.

In my work I reflect that the seamless continuity is, in my opinion, very dangerous because it’s as if nothing happened. That, as Walter Benjamin said, is the proper tragedy, that ‘everything continues as if nothing had happened’. For me that is dangerous.

The head of the Catholic church in Rwanda came up after the genocide and said you can’t put responsibility on the church in general, you have to blame individuals. But I think there is a case for institutional responsibility. And there is certainly collective responsibility from the church – both from the perspective of the leadership and the common people who were seriously involved in the killings. You can’t just say, ‘We switched off for three months and then after three months we put on our church mantel once again.’ It just doesn’t work.

AB: Could you talk about the state and reconciliation in the wider society? Has the Rwandan state come to terms with what happened 20 years ago?

RB: Reconciliation as a whole, we should be really pleased with what has taken place.

I have been very critical of the process of reconciliation in some instances because I felt it was state monitored and inspired at first – as if the state was saying, ‘we create the conditions and the rules of reconciliation and you have to follow them’.

The earliest institution was the Commission for Unity and Reconciliation which was a political body, but at least it had the ambition of setting out the agenda for reconciliation. And then obviously with the laws on the genocide it was another path to reconciliation, and they must go hand in hand.

There is so much law can achieve, and just can go a long way, but it is not enough for reconciliation. If you take reconciliation in its absolute value, then I think for all the criticism the gacaca court, the common people, the population at the centre of the debate on justice and reconciliation, the people faced their demons and one another on a platform where they understood one another. It wasn’t perfect – and it could not be because of understandable circumstances – but I think it helped to go to the heart of truth in many cases, and it opened the door for individuals to be able to speak to people they might have offended.

So after gacaca it is an ongoing process which is reflected in new initiatives like the Youth Connect Dialogue, a dialogue between people who were very angry in the genocide, who can’t be held responsible, but still live with the consequences of the genocide on either side. Under the auspices of Art for Peace, they have been meeting young people throughout the country to debate what it is like to take on the responsibility of your parents, and to take on the suffering and the pain of your parents and to try to find a way forward for this young generation.

Out of this Youth Connect Dialogue, came a new programme, Ndi Umunyarwanda, trying to create a national identity based on ‘Rwandanness’ instead of ethnic solidarities.

We’ve come a long way and there is still a long way to go, but it’s hopeful. I’m optimistic. If we have managed 20 years without going back to killing one another – it hasn’t been perfect, we still have cases of maybe, crimes committed by the current government or the army, and how will they be dealt with within the process of reconciliation? – but the balance overall is a positive one . I hope the process of reconciliation can really be a grassroots exercise because there have been programmes where communities, rural communities, sometimes felt it was being imposed upon them. But if they own the process in the future that’s when real stories and histories of reconciliation are going to come alive. I’m excited because that is what I’m researching – using oral histories to understand reconciliation, to understand justice. So people, individuals, involved in sorting out complex situations.

Reconciliation as a political programme has to end at some point because governments can’t sustain such a programme indefinitely, so it will be decentralised and individualised and particularised. I suppose within the next 10-15 years more people will have found a way to deal with their conscience (ie the perpetrators), found their place if they were just witnesses, bystanders, and, I suppose found a bit of peace and a way forward if they were victims.

AB: 20 years without further violence. Is that down to grassroots reconciliation? Or is it the strength of the Rwandan state that has bound the country together?

RB: More the second than the first. States are controversial. I suspect we needed a strong state after the genocide to stabilise the country and bring security because justice, reconciliation –anything, any living together – becomes impossible if there is no security. So we owe it to the state for having created the conditions for stability for all those initiatives to happen within not a safe, but a controlled environment. But also you have to give credit to Rwandan communities at the grassroots level because they had to put up with an awful lot for the process to succeed. Victims and survivors had to endure co-existing with people who threatened their lives, threatened by extermination. And some Hutu people as well had to put up with a lot, they had family members in prison and they knew those people were innocent and they waited to give a chance to the state itself to create conditions where cases could be tried. Individuals paid quite a price in terms of allowing conditions that enable a dialogue.

AB: People sacrificed themselves to enable society as a whole to make progress?

RB: Yes, I think when we look back we will see that every Rwandan, after the genocide, had to put up with an awful lot, both groups have to be commended for allowing the state to almost impose itself upon their lives so that we can all enjoy some relative peace together in the time of tension (because tensions were there), but nobody wanted the violence to erupt again.

There are 2 more parts of this conversation, coming up in the next few days on Pod Academy – look out for them.

Dr Richard Benda is a research fellow in Religions and Theology at the University of Manchester His doctoral thesis, Weighed and tested: Christian and Muslim communities and the Rwandan genocide addressed key questions in relation to religious authority and the role of faith in response to the complexity of African identity-based conflicts, of which the Rwandan genocide is an extreme case. This research is designed to be a contribution to the process of peace building and reconciliation for the people of Rwanda.

Tags: Christianity, Islam, Rwanda, Rwandan Genocide

Pingback: Muslims are terrorists? The Muslim community in Rwanda proves the opposite. | rwandakigali