Transcript

This podcast on the rainforest music of the BayAka was produced and presented by Jo Barratt

It is part of our series on ethnomusicology made with the sound archive of the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford.

In this podcast you’ll hear the sound of the BayAka people of the Central African Republic. Specifically a collection of recordings made by Louis Sarno. All of these recordings, and more, are available on the Pitt Rivers Reel to Real sound archive website

In other programmes in the Pitt Rivers series, we look at different aspects of ethnomusicology, but here we are taking an in-depth look at a single collection of sounds, the rainforest music of the Bayaka and, through it, telling some of the story of the BayAka people. Guiding us through this podcast is Noel Lobley from the Pitt Rivers Museum. The interviewer is social anthropologist Sarah Winkler Reid from the University of Bristol.

Here is Noel to introduce us to the man who made these recordings:

Noel Lobley: Louis Sarno is a guy from New Jersey who fell in love with the BayAka music from the rainforest of the Central African Republic/Northern Congo. He bought himself a one way ticket, a tape player, batteries and some spare tapes to record the music and more or less never came back. He became a part of the community and over the last 30 years has made the world’s most important collection of BayAka music. It currently stands at about 1500 hours worth of music recorded. He has recorded every hunter-gather community and mapped its relationship to forest and the environment. He has gone from being a recorder to an advocate, living amongst the community and helps to mobilise healthcare.

BayAka singing has been well documented, but the instrumentation has not been looked at as much.

Amongst the community he has been living with, there is a beautiful four note flute called a mbyo (sometimes called mobio), it is made from climbing palm. A musician may play it for many reasons, sometimes for entertainment. But it is usually played at night, when the rest of the camp is asleep. They will wonder around the camp and it is played to enter your dreams. If you think about it, when you are asleep, the sound echoes around the canopy and the forest is sometimes described as a cathedral, due to the way the sound resonates. A musician may play at night for benediction, protection or for the camp.

Bear in mind Louis has recorded it in its context: its relationship to the rain forest, acoustic and environment. When you listen carefully, you can sometimes hear musicians playing against the canopy, so the overtones weave in and out as the musicians are playing. So sometimes it sounds like two people singing perfectly together.

You can hear the forest soundscape. You can hear the insects, and if it is a heavy sheet of insects, it can tell you whether it is late at night or early in the morning. Sometimes you can pick out the pulse of the insects the musicians are playing with. You can sometimes hear they are playing to a rhythmical structure that is in the forest. The music is very much of the forest and a gift for the forest. Most of these instruments are made from the forest. It sounds very much to me like an exploration of the acoustic properties of the forest.

In this community, it is not played any more. Over the time Louis has been there, there were three master musicians, but they have all died. The last player who played this, and who knew how to make the flutes gave one to Louis to look after. Louis says he never hears it played anymore. No one knows how to make it, or which particular plant is needed to make it. He looked after the last flute (mbyo) in Yanduombe and it was on its way to us in April earlier this year. There has been oucoup d’état in the Central African Republic. Seleka Rebels have overthrown the government. President Bozize has fled. Rebels have overtaken the capital. In April last year, Louis posted from the Central African Republic on facebook (he had intermittent access to the internet via the WWF), that the BayAka community he lived with (who live part of the year in a settlement in Yandoumbe and the rest of the year spend time in the forest hunting) were forced to flee back into the forest because rebels had overrun the town they were staying in. The rebels were looking for money, and targeted Louis’ house because they believed that because he was American he would be wealthy, but he is not. He lives hand to mouth. They destroyed his house and everything that they could find, including the last flute. I wouldn’t want to pretend a sound archive could solve political instability in the Central African Republic, but, it is obvious that an archival record of something as beautiful as this mbyo becomes more and more important.

Sarah Winkler-Reid: Why weren’t the master musicians being replaced?

Noel Lobley: His [Louis’] take on this was that there was a laissez faire attitude towards music making. No one is told to play the mbyo or the geedal. No one gets told to do anything. If someone is interested in studying it, then they can. Perhaps the children weren’t interested. I don’t know to be honest. I can only speculate its function changes within the community. If children are not picking it up, then it will not continue. The last 3 master musicians died and that lineage did not carry on for some reason.

I have spoken to Louis recently about building another one. To find out what the vine is that is needed to make it. There must be someone who knows. Louis said he was going to renew his efforts to find out whether it can be rebuilt. We have recordings so we can build one here, but it will not be made out of the same material. His take on it is a laissez faire attitude. If it is meant to change, it is meant to change.

SW-R: You have talked about the coup, and the BayAka having to escape into the forest. How are things changing otherwise for the BayAka?

NL: They are a hunter-gatherer community, and within their own country are increasingly being marginalised. Their hunting pathways are shrinking and reducing. Partly, because of the increase in the size of National Parks and they are losing their permits to hunt. National Parks are also a good thing for conservation. It is becoming harder and harder to survive in the way of life they are used to. They are increasingly reliant on more indentured labour for non-BayAka communities. Perhaps doing gorilla tracking for the WWF, doing more farming for non-BayAka communities. They are becoming more sedentarized, spending less time in the forest, more time in roadside settlements. To quote Louis, this has led to increased alcoholism, there wasn’t really a cash economy before. These are common changes that occur in communities like this. Their hunting was traditionally very sustainable. It was net hunting, they used handmade nets to catch small game. Not animals that protected by the WWF such as: elephants and gorillas. They don’t use guns. They use nets, a system of songs, sounds and symbols to startle the animals into the nets. Louis estimates that about 50% of the animals escape from the nets, although he realises this is frustrating it makes the wildlife sustainable. Now the bushmeat trade is coming in with hunters from other countries, such as Chad, coming in with guns and they are blasting the animals out of the forest – making it harder for communities such as the BayAka to survive the way they normally do. Those are some of the changes.

Anyone who listens to the music will tell you, the quality of the music is dependent upon access to the forest. So if access to the forest changes, the music changes, the polyphony will erode. Even in the period Louis is recording which is more than 30 years, you can hear the simplification of the polyphony in lots of cases. For example there would be about 60 women singing in a roaring choir 25 years ago. In the more recent recordings this happens less and less because smaller communities are going into the forest for less time. The complexity of the singing reduces inevitably. This is because the polyphony in the forest is about how people relate to each other in the forest and how you make a community. For example, they sing for the success of the hunt the next day. Singing coordinates everybody and creates a resilience and gets everyone on the same wave length. You can’t have anyone distracted. The singing is partly about mapping the community, if you like.

Louis says drumming styles are starting to become more complicated. He says there are new styles of drumming the teenagers are developing because they are by the roads more. There are new forms emerging, it’s not just a simple process of erosion.

SW-R: So is the narrative quality of the music changing, as well as sonic changes and instrument changes?

NL: Some of the music is not narrative music. But, some of it is. It is called Gano. They are sung fables. They are stories that move from storytelling into song, and back into story telling. They have a clear narrative. I do not speak the language BayAka, but I have some understanding of this form, through Louis and research. These Gano tell the story of BayAka creation, and the story of the creation of the forest by Mkumba (God). All the animals used to be people. When people did something that displeased God, he turned them into various animals. These stories get told by master story tellers – there is Makuti in there, and others who have died, like Ngondo. They are told with exaggerated voices about the history of BayAka communities and the history of the forest. And they work in contemporary news into those stories, and they will work in events and gossip. It’s an organic form that evolves, so, for example, if there are now more gunshots in the forest, you wouldn’t hear them in the recordings 30 years ago, but now you will. They all find their way into new stories. Or if someone has been put in prison for killing an elephant. These narratives do change, they are not just archaic representations of the past. This is an oral story telling culture, inevitably it is going to blend the present with the past and I think you can hear the changes in the content.

Louis has said his long term dream is for the BayAka people to have self-representation. For them to be able to address the rest of the world about the issues that are relevant to them. His view of it was to have a blog hosted where they live that they can upload the issues that affect them to the rest of the world. He says that’s what they want so that they can present for themselves, their songs, their stories, their issues. Rather than it being mediated through him. At the moment it is inevitably being mediated through a collector like him.

The Geedal is a beautiful six string bow harp. It is typically made of local wood. Perhaps have animal skin stretched across the resonator. Six strings, occasionally seven. It is believed that it is not an indigenous BayAka instrument. ‘Geedal’ may even be a corruption of ‘guitar’, there has been some speculation about this. Musicians play variations in the community Louis lives in and might play all night.

You can hear these absolutely stunning variations that continue for hours and hours. Sometimes with just variations of the notes. It is played for entertainment and pleasure. Musicians may also wander around and play it at night while the camp sleeps. It is a layer of protection, salvation for the sleeping camp. It is still played quite a lot amongst the communities.

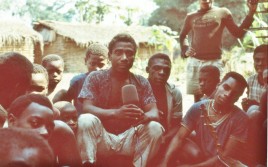

When you listen to the recording, it is so full of life, humour and laughter. You can hear this Balonyona he is a master player and story teller. The man who has a gruff voice is Zalogwe he is grabbing the microphone and pretending he’s a pop star (he is also the man with the microphone in our main picture). He is addressing Bangui, ‘Hello Bangui’ (the capital of the Central African Republic). He is on radio, he’s presenting the BayAka to the capital. They go in and out of songs. One is called Bonanay, which is one of Balonyona’s where he sings about a new year’s eve party that didn’t quite happen because they didn’t have enough money for beer – this became a famous story that was recycled throughout other stories.

When we arranged to digitise the whole collection which was a thousand hours to begin with and now 1500 hours in its current state, we didn’t really know what condition it would be in. The collection had been in the rainforest for quite a while and stored under a bed. Then in a suitcase in a storage room in Oxford. These are not ideal conditions for looking after tapes. Particularly humid places such as the rainforest. The first batch of recordings I heard was well over a year ago. I had been waiting a long time to hear these recordings. The quality was superb, and the music was superb! I was so excited that I was running up and down the museum telling everyone ‘they are superb!’ From our perspective it was the beginning of pulling the recordings out of storage and hearing the life that’s in them. This is one of the liveliest recordings that I have heard, there is so much fun and life in them. He (Louis) did not want a tame session as the people who do with microphones for academics, who ask people to perform for them. He wanted a snapshot of music that would be played if he wasn’t recording. So I think there is something he is looking for. This is one of the earliest recordings from 1986. He went there in 1985. This is at the beginning of the collection that was going to emerge into an amazing record of BayAka music and life.

SW-R: Do the women and the men tend to make music separately?

NL: Any collector , any recorder, is an editor – they all have their own biases. They have their own decisions about what they think is important – that is the importance of someone like Louis working on collections like this. So you know what is missing, what biases and prejudices are being explored. Louis’ heart is in the women’s polyphony which is absolutely majestic. Most of the choral singing/polyphonic singing, it is mainly the women. Where there are hundreds of hours of the polyphonic songs it is mainly the women. The instrumentation is mainly the men, such as the geedal, mbyo and the percussion. But, you do hear the men singing with the choirs, and it is nicely blended. When there are these polyphonic songs, there are ceremonies that go with them and spirits that come out at night. Sometimes these spirits come out at night and are dressed as leaves and sometimes they glow in the dark. There are certain clear roles that defines who the spirits are. There are male and female spirits. There is a women’s song called Limboku which is a celebration of female power and female sexuality. Men are not allowed to sing or really hear it. It has its own spirit, which is a hooting sound. There is dozens of hours of the music with the playlist on the website with Limboku and other songs. To quote Louis ‘the men don’t like this song’, because the songs mock male impotence and celebrate how the women do everything and say how powerful the women are and how men are limp. The men do not want to hear it, so they try to start another song when they hear this or leave. There is a clear gender division there. There is also a labour division as well in terms of who hunts, who gathers and who collects honey. This is reflected in the expression.

SW-R: Do men have a comparable song to the women’s power song?

NL: There is a lot of different genres and Louis has recorded them all. There is So which is a comparable form where the men get together to sing masculine songs that explore who they are. There is a very common ceremony for a spirit called ejengi. It is a beautiful spirit that is dressed from head to toe in raffia palms.

When the spirit dances it looks like cascading waterfalls. It is a male initiation dance, amongst other things. There is a belief that the ejengi spirit is a phallic spirit, because it is a boyhood into manhood spirit, so I would imagine those songs are within that in some way.SW-R: when you talk about spirits in this context, what do you mean by that?

NL: The spiritual realm is an important realm. There are some things that are not supposed to be said. A lot of the music is designed to call out forest spirits. The music is a gift for the forest. It is a gift for the forest – the forest has a god and lots of the music is designed to call the spirits out and make them dance. And it won’t happen unless certain conditions are achieved. So in the Boyobi, which is a ceremony for the net hunt, the group singing, the drumming and the singing are all designed to ensure there will be a successful hunt the next day. That needs coordination, it needs rhythmic power, it needs singing power. It needs people to sing and drum well. If the spirits are happy they will emerge from the forest and they will communicate with the group. They speak in archaic language and they have these ‘uhuerr, uhuerr’ voices, sometimes falsetto, and sometimes it sounds as if they are admonishing – it’s a very curious kind of sound. And they’d be heard more than they’d be seen. In many ways, they will conduct the group, with call and response. They’ll go ‘Ee-ay-ha, Ee-ay-ha’….the drumming stops….and you hear a call and response between the spirits and the group.

It is designed to bring people together and I think you can hear it. It would be wrong to say who the spirits are, I’ve been told by anthropologists, they occupy a particular realm and function within the community.

SW-R: The music, the culture. What is the future?

NL: The collection Louis has made here, this record of the entire range of music making of a single hunter gatherer community, that cuts across more than a generation, obviously maps musical and social change. There are lots of issues affecting this BayAka community – and this is just one community, there are many others – and it has, if you like, been privileged by a recorder. But there are other BayAka communities that experience the same issues. At the moment, the whole country is in turmoil, so it is a difficult time for all the BayAka and they have retreated into the forest.

There are various health care workers, NGOs and others who do work with the community, and I think it is really important to raise such issues. But if a sound archive just presents a picture of the way things were, it can be quite idealised, so I am sure there is a way to link a collection as important as this with contemporary realities. It’s easy to raise awareness here in this ountry with events at the Pitt Rivers Museum or elsewhere (there’s going to be a bit exhibition in Holland, I think, organised by a billionairess. She wants some of these recordings because she is showing images of the BayAka).

It is easy to do those things to raise awareness internationally and mobilise resources to reflect what’s happening to a community today. But I think it is most important to listen to the BayAka themselves, to hear what’s important to them. Pitt Rivers is very strong on its relationship with its ‘source communities’ and what interests me is how you do that through sound. How you share the sound, how you share the resources, and reflect the contemporary reality through a historical record.

The ejengi, we mentioned, the initiation dance. When Louis was here he selected particular recordings he wanted to take back (the archive isn’t held in the forest any more), but there are not many ways of playing it. He has a CD player, a few people have phones, but he took back certain recordings. He identified some ejengi recordings from over the border in Congo where ejengi was very vibrant and took them back on CDRs. Within two months I had an email saying they’d been played to death! And had led to a renewed vigour in the ejengi, including more, re-performing of certain stages that had dropped out because they’d forgotten or it had changed. And people started coming from other areas to watch the ejengi here. So, again, other recording, going back, has begun to trigger some things again.

What interests me is how you use a record like this to reflect the contemporary things we talked about – the disruption of the flute, what’s happening in the country. A sound archive might be one way of mobilising resources and a community that is interested.

Notes:

The rainforest music of the BayAka is carried in the archive of the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford

Why not find out more on the Reel to Real blog.

And as you can see from this video, Sound Galleries: Music and Torchlight, the Pitt Rivers Museum is a great place to visit

Photographs: All photographs in this transcript were taken by Louis Sarno and are reprinted courtesy and copyright Pitt Rivers Museum. See more photographs.

Tags: Central African Republic, Ethnomusicology, Louis Sarno, Pitt Rivers Museum, Rainforest, Rainforest music, Reel to Real

Pingback: Ethno-musicology – The Rainforest Music of the BayAka | Learning Change