Transcript

This is the first in a series of lectures from the Huston School of Film and Digital Media in Galway, part of the University of Ireland.

In this lecture, Irish feminist filmmaker, Pat Murphy looks at what are the influences on her as a filmmaker – the people, the events, the ideas and the contexts that have influenced her work.

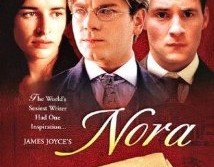

Pat Murphy grew up in Northern Ireland, and studied in London, at Hornsey College of Art and the Royal College of Art in the 1970s. Her films Maeve, Anne Devlin and in 2001, Nora starring Susan Lynch and Ewan McGregor, have made her one of Ireland’s most important film makers.

Pat Murphy: Influence can propose the notion of a fixed position, of one separate entity affecting another, but from my experience I’d rather speak of the porousness of influence, of border crossings, the non recognition of boundaries.

These are all geographical references but I think influences are like geographical features in a landscape because they operate at different speeds and scales, and come under different types of pressure. And who knows where they begin. Their origins are secret and personaland sometimes an academic perspective can harden and falsify what has to remain private and fluid. So when I was asked to speak, and I asked my self, ‘what is an influence – first of all, there is a resistance to talking about it, then I decided I’d approach it by asking some very simple minded questions.

When you are a child, you are like a landscape open to the rain. You can’t control what influences you. So when we talk about ‘influences’ do we include this period of childhood when there is no element of choice? Or is influence a stepping stone, a means of investigating and transforming the questions raised by these earlier pressures? Is an influence someone who supports your ongoing questions and doubts? Is work, artwork, an artefact or film that we feel a connection with the same as an influence? Is influence like seeing a painting or hearing a piece of music and realising you’ll never look at anything in the same way again?

There are huge influences that change and challenge our direction in apparent ways, but influence can also be a casual phrase – something ordinary said in the moment, which in retrospect you realise has set you off in a new direction. It can be like compost, filtering through like rain.

In terms of my own influences, or what could be perceived as influences from the outside, I realise they actually don’t have much to do with me at all. I realise we all live in an interesting time in terms of what we can use as influences in making films, or making art, or any kind of creative activity. I was fortunate to live in a time of great social change and great challenges that were going on. But at the same time, when I look back the things that really changed were very small moments.

In May 1968 I was in school in Belfast and a teaching assistant came in to take over a class and she brought in a pile of newspapers and she spoke about what was happening in Paris. She showed us different newspapers and different ways of reporting on what was happening. I really feel that this was the first moment for me that I realised the media could manipulate the system, and how language – that you remembered as something very clear – was actually a product of the consciousness of the time, that was being fed by different types of information. And also how language actually structured the memory. It was the first time I started thinking of images as something to be investigated. This was the moment (rather than being at film school or coming into contact with filmmakers who were investigating film as much as being involved in the process of film making), this was like a turning point.

Another moment would have been at Hornsey School of Art, prior to a time when feminsm was really being talked about, before it was really regarded. I had a friend called Jacquie Pocock who disappeared. But I remember her art very clearly. She had a child of about 10 years old. It was a terrible struggle, I think for this woman to get into the college every day, though none of us paid any attention to that whatsoever. She decided to make art about her child and what she did was made these tapestries that were based on photos she took of the child, and she would embroider the tapestries. She also made these ceramics screets – a house that would be repeated to create an estate or to create a street of houses (I realise you’re all dependent on what I say, rather than seeing what this was).

I remember feeling ambivalent at the time. We had a tutor – who has remained a friend -who told me the reason he didn’t like women’s art was that it was like knitting. I was so offended by that, but then I thought, hang on a second there is a core of reality in this, because you are talking of a process and working with media that are not recognised as suitable media for making art. My friend’s work simply wasn’t recognised, was off the radar, in a world where people were making sculptures that looked like Anthony Caro or paintings like Jackson Pollock – that sense of scale, the ‘unified statement’ and having the thing operating in one piece on a wall, or occupying one space on a floor, was where the big money was in terms of art at that time. It seems to me that what she was doing – in a very gentle way – was pulling the ground from under the feet of those very large pieces of art.

Then also an artist called Maurice Hatton, he wasn’t a tutor, he just one day walked past me when I was making masks. I used to have this huge studio in an old piano factory in Fitzroy Rd London and I would make installations, shoot little bits of film, and make objects that would be part of these films. One day when I was making these masks he walked past and said, “You know you must read this book – The Theatre of the World by Frances Yates“. So I read it and it opened up a whole space about the notion of objects – and other books by her like The Art of Memory, and the Rosicrucian Enlightenment – the notion that objects could be used to trigger memory, or to contain whole narratives, the ways plays were performed in different eras, that encompassed these huge kinds of notions. That was very large for me at the time.

In terms of influences, we can talk about individual people, but what we really need to talk about here is the idea of permissions and contexts. The search for filmmakers, indeed for any artist, is the search for a context in which to make work, and a context that will affect the work. I think it goes back to this idea of being porous, not fixed and blocked. John Boorman talks about it in Money into Light when he is talking about his relationship to Ardmore film studios. He says ‘all I ever wanted to do was to create a space where I could get my films made’. In films like Excalibur and Zardos and other work he did at Ardmore can be seen this monumental urge to create a space where he could make this work.

To go back a bit to what I was saying earlier, when I got to the Royal College of Art film school (I don’t want this to get too confessional and anecdotal, but I can’t see any other way to talk about what I want to talk about), Dai Vaughan ran a course in documentary filmmaking and this course was a look at establishment documentary and oppositional film making. He looked at Northern Ireland – while for me Northern Ireland was something to get away from, even though those politics were going on, I couldn’t see a way to make it work, I couldn’t grasp what was going on. My escape had been into working in a formal art world, I couldn’t see how to make it work even though I had made this small film called Rituals of memory which was very much informed by the war in Belfast at the time. But influence is not only looking at someone’s work and seeing how you are affected by it and how you use it, it is also looking at a situation and reacting against it or identifying a lack.

What came out of this period for me was that I identified a lack in documentary filmmaking in terms of describing or expressing what was going on in the north of Ireland in any compex or textured level. There were at that time a number of ways people received information about the north of Ireland – there was a newsreel language, there was Panorama, News at Ten, World in Action – even when they were investigative documentaries there was a language that was being used – the powers-that-be check out in an anthropological way what is going on and then inform us with the answer. And even the opposition work done at that time was locked into the same paradigm because it was simply challenging that – everything seemed to draw unconsciously on the cinema verite notion that because you’re there with a camera, what you’re filming is actually the truth. This doesn’t take on board what the filmmaker’s position is in relation to all of that.

So for me that was the point at which a number of pieces of work came together and evenutally evolved into the film Maeve . Also at that time Brecht and the work of Godard were very important. And Laura Mulvey came to teach at the college (a couple of years after Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema had been published).

These were groundbreaking times. It was not hard to respond to them. There were a series of permissions and contexts that had already been set up in relation to making certain kinds of work.

I think there is an issue that becomes a difficulty around the idea of things coagulating around 2 postions – the influencer and the influenced. It it is important to re-look at that time – particularly at Brecht – at the way we absorbed his ideas around ‘identification’ in cinema – identification with oneself as a film maker and identification with what the main character in a film is meant to do, as the carrier of meaning, as the figure with whom the audience is meant to identify. This finds expression in Maeve where the main character functions as a series of questions – she is someone who stops the need for the audience to like her, or follow a single narrative line with her, or begin and end a story with her.

I read an interesting quote from Philip Glass on this when being interviewed about Tibetan Buddhism and its affect on his work. Although he has been influenced by Tibetan Buddhism, he was very careful not to get into mystical notions in talking about it, and he spoke very strongly about the influence of Brecht, and how, though Buddhism can address and challenge the notion of the fixed self, for the westerner those issues are there in Brecht who raises the notion of the cherishing of self which I think is what conventional mainstream cinema does in creating characters that are somehow cherished by the script and cherished by the audience.

The other thing I wanted to say is that influence can also be an incredible block. Despite the work of film theorists, teachers, filmmakers in creating a context for younger women filmmakers, I think every young woman filmmaker starting out feels somewhat isolated. There are a number of reasons for this – and it is something we should talk about. Despite the dearth of women’s films, there is a calcified cannon. Even the few films I’ve made – because they are so few – have been put into this cannon. And one of the things that is important is to find a way to construct a lineage for women, so you know you are not walking out into a place with no ground.

But on another level, I came across this beautiful phrase – ‘the pleasure of unmediated concentration.’ That’s what people starting out making films need to feel – that they are the first ones doing it. You need to feel that you are a pioneer and that this hasn’t been done before. One is now so overwhelmed by information and imagery, that what I find with my students is that they think, where do I fit in? everything has been done. What we need to communicate is that all these influences are around but they haven’t been concentrated in this particular way, as they are for you.

This is like the thing of Joyce. Growing up in Ireland one inevitably comes into contact with, and is influenced by, Joyce. My first film, Rituals of Memory was actively influenced by Joyce – working with stream of consciousness and structure in film.

But at the same time you are aware of how deadening certain qualities associated with Joyce can be – elegy, nostalgia, memory, distorted hopes. He has exploded language and the way things can be written about from that modernist period. Everything since is like an echo moving out.

So the Nora film gave me a chance to come at him in a more oblique way. So when I have said in the past that it isn’t a feminist film in the way Anne Devlin or Maeve are, it’s not that it is ‘post feminist'(i have a difficulty with that phrase) – in a way that is perhaps more dubious, I was interested in understanding what he was about through his relationship with her.

Permissions and contexts are important here – it was Edna O’Brien who enabled me to make this film. I remember we had started rehearsing the film and one day it landed with us, this is actually James Joyce we are dealing with here, and everybody froze and couldn’t work for the rest of the day. So I suggested we stop for the day.

On the way home in the car, she came onto the radio. It was a series called the Giant on my shoulder. It was a time during the Joyce centenary when authors were asked about Joyce and his influence. John Banville said it stopped him in his tracks, he just wanted to get away from it. I had felt this too when I was younger – how could you write anything when it has all been done. Nothing you could ever do could be better, so why even begin.

But Edna O’Brien was saying no, this isn’t where you look for influence, what you do, is you go and look at what you’ve done, then charged with energy you do the same thing.

Tags: Edna O'Brien, Film studies, James Joyce, Pat Murphy

Subscribe with…