Transcript

United Nations officials have called for a complete end to genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) to ensure the dignity, health and well-being of every girl. There has been much talk about ‘zero tolerance’. But is zero tolerance the most effective way to

end this abusive practice

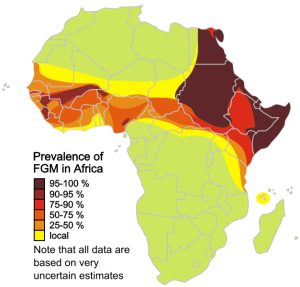

A huge international drive against female genital mutilation (FGM) by women’s rights and health campaigners has resulted in the outlawing of FGM in many countries,. But it continues to be widely practised.

Amanda Barnes talks to Dr Kirrily Pells from the Young Lives research study at Oxford University’s International Development Department, about their research on FGM in Ethiopia.

Amanda Barnes: Kirrily, a Young Lives study looked at FGM in Ethiopia and the efforts the government’s been taking to eliminate it there.

Kirrily Pells There’s considerable variation in the country between different ethnic and religious groups and between the different regions of the country in terms of the prevalence of FGM, which form of FGM and at what age it occurs. For example, it’s less common in urban areas.

In 2011 the proportion of girls in urban areas who underwent FGM was around 15 per cent compared to 24 per cent in rural areas. And then between the different areas of the country it ranges from between ten percent in Addis Ababa, the capital city, to about 60 per cent in the Afar region in the east of the country.

And there are also differences in terms of what type of FGM is practised. In the north of the country it tends to be performed on girls shortly after birth and takes the form of cliterodectomy, which is the partial or total removal of the clitoris. The other form practiced in the northern region of the country is excision, which again involves the removal of the clitoris but also the removal of the inner labia or the inner and outer labia. In the south of the country FGM tends to be performed just before puberty and it’s very much linked to adolescence and preparation for marriage: and the form practised there tends to be clitorodectomy again. In the east of the country in the Afar and Somali regions of the country infibulation is practised, and this is what’s often viewed as the most extreme form of the practice where both the clitoris and inner and outer labia are cut off and then the resulting wound is sewn nearly shut, just leaving a small hole through which urine and menstrual blood can pass.

AB: What’s the Ethiopian government doing at the moment to try and get parents to stop subjecting their daughters to FGM.

KP: The Ethiopian government has taken a very strong stance against FGM. It’s designated it as a harmful traditional practice and it’s prohibited by the 2005 criminal code. And this sets out the theories of punishment, including fines and imprisonment, for both those who perform the cutting and also those who commission ceremonies: whether that’s parents or other members of the community. And it’s also a crime to publically encourage the practicing of FGM. Alongside the legislative efforts, the government has promoted a wide range of other preventative actions. This includes advocacy campaigns within schools and the media and encouraging local associations to also be active in promoting knowledge around the adverse health and social consequences.

Alongside the government there’s also very active civil society. NGOs have been very active in trying to combat FGM: both national and international NGOs. And there’s a national network of organisations that are working together to try and combat the practice. AB: So how much have things changed there then? KP: Well, within the country the prevalence of FGM is declining, although quite slowly, and also there’s variation between the different regions. For example, the percentage of mothers who had one daughter being circumcised in 2000 was 51.7 per cent. But by 2005 this had reduced to 37.7 per cent. But the greatest change was seen in urban areas, such as in Addis Ababa, and was much smaller in other more remote rural area such as the midland Oromia and southwest SNNP region.

AB: You were saying earlier that it was now criminalised and the punishments could be quite heavy-handed. Do you think that might mean that those figures that you quoted might not be necessarily reliable?

KP: I think that’s a big challenge for data collection. The most recent demographic health survey didn’t collect data on FGM precisely because it is an illegal practice. Instead, what researchers have to rely on in survey data is often around perceptions – so ‘do you believe that it’s wrong to have your daughter circumcised?’ And of course as we can imagine, there’s often a big difference between what people might say that they prefer and what’s actually going on. And indeed the Young Lives research has shown that one of the results of having strong punishment for FGM is that the practice may be being driven underground and taking different forms as families find alternative ways to navigate around the ban.

AB: So despite the number of girls undergoing FGM having dropped, possibly quite dramatically, nearly a quarter of all women say that they’ve had it done to them according to the Young Lives report. So you’re still talking about millions of people affected. Is this because there’s been a problem getting the message across or is there something else going on? KP: No, I don’t think it’s a matter of knowledge. Within the qualitative interviews that we conducted with children and their care-givers and community leaders there was widespread knowledge of the ban on FGM. And also people were aware of the health messages that have been communicated through the media and the adverse health consequences of FGM. So I don’t think that it’s a matter of ignorance. Instead I think it’s a question of needing to understand what actually drives the reasons why parents or girls themselves might choose to undergo the practice. Now this can vary between the different regions of the country.

But most commonly FGM is very much linked with marriage and is seen as an essential preparation for marriage because it’s seen as ensuring girls’ moral and social development. Rather than being seen as harmful to girls’ wellbeing it is seen as protective. It’s seen as ensuring girls don’t have sex before marriage and therefore their reputation within the community is assured, they are seen as pure and then they’ll be able to get a husband. And this is particularly important in a context where families are very poor and there are limited education and work opportunities for girls because marriage is the only way in which families can ensure that their girls all get to be provided for.

AB: So do you think that threat of prosecution and the criminalisation has been a major deterrent or not?

KP: I think it plays a role. And I think that certainly people are aware of punishment and express fear of being punished. But I think, because of the strength of the rationale as part of the cultural context, I think that instead what’s happening is that the nature of FGM is changing. So for example, some of the girls within the research talked about how instead of the ceremonies taking place during the day, they were taking place at night now to try and avoid official attention. And this could actually place girls more at risk because it’s taking place in the dark or being performed by less experienced practitioners.

AB: There seems to be quite a build-up of support for the idea of ‘zero tolerance’ for FGM, for example there’s now an international day which is called The international day for zero tolerance of FGM. Do you think that that idea of zero tolerance is counter-productive, or do you think it is such an abusive practice that it should be criminalised?

KP: I think you have to start with what’s going to be the most effective strategy for eliminating the practice, or what approach is most likely to work. And I think there’s increasingly more evidence that just relying on legislation or a very punitive approach isn’t working, as Young Lives research in Ethiopia indicates. There’s also evidence from Senegal that came to the same conclusion – having legislation that’s implemented in a very harsh way can actually lead to the practice being driven underground with more risk to girls. So I think instead that the starting point is that it’s better to work with communities to engage in processes of dialogue that involve the whole community and not just officials. Because with the Young Live research in Ethiopia, we saw that officials were very adamant that FGM should be banned and believed in making a strong stand. But that didn’t necessarily mean that other members of the community believed the same thing. So you need to involve the whole community to make it a community-owned process rather than a top-down imposition from outside the community. That said, I don’t necessarily think that it’s wrong to have something in law because I think that can provide a useful framework and can set an important standard. But I think it’s how you then go about implementing that and the fact that you don’t just rely on legislation alone but you need a whole range of measures that go alongside that.

AB: What sort of things have you come across people reporting to Young Lives about what’s happened in the community to girls who haven’t had it done to them and the sort of stigma that results.

KP: Girls have described a lot of peer pressure to undergo the practice and the girls who’ve not undergone circumcision have been bullied, their fears – whether or not these are realised we don’t know – are that these girls won’t get husbands. And so this is why girls were also reporting that they themselves were organising circumcision ceremonies. Even though their parents weren’t forcing them to do so, they were arranging them themselves in order to make sure that they wouldn’t face stigma in the sense or exclusion from the community.

AB: Some activists would probably say that respecting traditional cultures is no excuse for allowing women’s rights to be violated. Do you disagree with that argument?

KP: I think that we can’t see culture as a static or a monolithic phenomenon. Culture’s dynamic and it changes. And also within a culture there are different practices and different voices. And I think it’s a question of working with different aspects of the culture that might celebrate women or women’s roles within the community and finding ways of promoting those.

I think even within the language of FGM we have to careful. Internationally, FGM has become the term that used but if you go into a community and you talk about mutilation, you’re immediately going to put people on the defensive because you’re going in there telling them that what they’re doing is wrong, even though they themselves have a strong rationale for doing it. And I think that’s then going to be detrimental to trying to build understanding and build support for gradually eliminating the practice.

So I think it’s better to work with people rather than creating tension and potentially driving things underground and making it more dangerous.

AB: Earlier you were talking about some of the consequences that were social and economic and psychological, and there certainly are significant consequences for people’s wellbeing. But do you think they should take priority over what really amounts to quite severe child abuse and cruelty?

KP: I personally think it should be eliminated as quickly as possible, but you have to think about what strategies are most likely to lead to that happening and what is going to be most successful and more sustainable. And although legislation has existed in a number of countries for several years now – banning FGM – the rate of change has been very slow. And there’s also limited evidence on what actually works in terms of engaging with communities and bringing about real and lasting change.

So I don’t think it’s an either/or. I think it’s that you need to build more opportunities for girls, particularly in terms of education and livelihood opportunities. Because if girls have other opportunities, there’s going to be less need for a practice that’s seen as securing their social and economic wellbeing because they’re going to have other routes to doing that. And indeed in Young Lives research we see very strongly that education is changing children’s roles and changing aspirations for the future. And what’s expected of boys and girls, for example care-givers talking about considering it being more acceptable for girls to get married later and to have an education first. And also to find work. So I think you need to build education and livelihood opportunities for girls. And alongside that work with communities to try and change social norms. But changing social norms does take a long time and it can’t be forced because it will then just be driven underground and there will be a fierce backlash. So if you want to successful you need to bring both the social and economic side alongside the cultural, and work with all aspects within a community.

AB: There’s been quite a lot in the media recently about FGM being practiced here in the UK and the government not having prosecuted any care-givers or parents who’ve had the process done to their daughters. Do you think there might be perceived to be a bit of hypocrisy with northern governments lecturing governments like the Ethiopian government about eliminating FGM when they’re really not doing very much about it here in the North? I think maybe some listeners might be thinking about that.

KP: I think one thing to mention first of all is it’s often assumed to be northern governments or northern-based activists lecturing the South. But there are very vocal African women and women’s rights organisations who are leading the way really in campaigning against FGM, and also working with communities, and perhaps having a greater voice and greater respect within their communities. Because they come from those communities and understand those communities and people know them. So I think it’s important for us not to set up a false North/South dichotomy.

But returning to your question, I think it’s a very difficult question for the government, firstly because it’s something that’s quite hard to detect. You do also have to think about the consequences of prosecution because there is a danger then that women who need help won’t come forward and seek the health-care that they need because they’re scared of being prosecuted or getting into trouble. So I can understand that there’s something in law and it’s frustrating because it’s not being implemented. But at the same time I think it’s important it doesn’t actually have an unintended consequence that stops girls, or stops women coming forward for help.

AB: So if there’s three thinks that you think that people involved with the communities in the countries like Ethiopia should be thinking about, what would your three points be for policy-makers and practitioners on the ground?

KP: Firstly, not to rely on legislation alone, but to think about a broader spectrum of approaches, which are indeed taking place in Ethiopia. But I think sometimes there is a focus on the law to the neglect of other approaches such as healthcare and communicating health messages in a way that are understood locally. And also encourage women who have undergone FGM to come forward for help. And as we’ve seen in the Young Lives research, a very heavy-handed approach can actually put girls more at risk by driving practices underground.

Secondly, the need to work with communities. Not to rely on a top-down approach, but to work with the whole community. Not just officials but children and parents and other members of the community, because social norms can’t be changed by just individuals. Because that sense of stigma and exclusion is going to prevent change being sustainable so you need to be able to build support within the community and to find other ways and other approaches. It depends within the community, whether FGM’s more a private matter that takes place after birth or whether it’s more a public ceremony as it is in some places in the south of Ethiopia. But one approach that has been used within communities is finding other ways celebrating girls’ transitions to adolescence and adulthood. Finding ways that don’t involve cutting.

And then thirdly to not just focus on FGM in isolation as a single issue, but to develop strategies that encompass a range of areas of intervention. As I was saying earlier about the importance of promoting access to quality education for girls: both primary but also secondary. Then on to training programmes of access to further education because that offers girls opportunities to study and to delay marriage and hopefully to find livelihood opportunities that reduce their dependence on men and on the need for getting married. And alongside that you need the healthcare, the reproductive information and building opportunities for political participation and women’s voices within the community. All of these areas together can help reduce what’s the underlying rationale for FGM.

AB: That was Kirrily Pells from Oxford University’s Department of International Development talking to Pod Academy about the Young Lives study’s findings on FGM. Kirilly Pells, thank you very much for joining us today.

Notes:

You can find World Health Organisation information on FGM here.

As Kirrely points out, there are high rates of FGM, even where it is banned as in Ethiopia. For example, In Egypt 95% of women have been cut, and there are high rates in some countries in South East Asia

You might also want to listen to Pod Academy’s interview with Nawal el Saadawi in which she talks about so called ‘honour’ based violence in Egypt.

Tags: cliterodectomy, Ethiopia, Female Circumcision, Female Genital Mutilation, FGM, Zero Tolerance of FGM

Pingback: Changing Children’s Lives: creating an enabling environment for child development

Pingback: Beyond ‘zero tolerance’ of FGM: transforming traditional practices