Transcript

14th January 1795

ANN HAWKINS was indicted for feloniously stealing, on the 7th of January , a feather bed, value 20s. a flock and feather bolster, value 10d. two woollen blankets, value 3s. a linen sheet, value 2s. a linen counterpane, value 12d. a looking glass in a walnut-tree frame, value 4s. a pair of tongs, value 6d. a brass candlestick, value 6d. a wooden pail, value 6d. and a tin kettle, value 4d. the goods of Thomas Norwood , in a lodging room .

How can we discover whether it was changing tastes and fashion that drove consumption during the industrial revolution or if it was falling prices (as goods were increasingly mass produced)?

One place we can look for evidence is the court reports of the time.

The records of the Old Bailey give a good idea of what ordinary people owned, because they record what was stolen!

In this podcast Dr Sara Horrell, Senior Lecturer in the Economics Department of Cambridge University, and Fellow of Murray Edwards College, discusses with Scarlett MccGwire how she and her colleagues, Jane Humphries and Ken Sneath, unravelled the consumption conundrums of the industrial revolution(Consumption Conundrums Unravelled, History Review Dec 2014) by looking at the Old Bailey records, which are now online.

We know that during the period of the industrial revolution (the late 18th and early 19th centuries) ordinary people owned and consumed more – coffee, tea, nice china, for example. And many historians have asked whether people were willing to work harder and longer to purchase these goods because they were fashionable, or whether it was just the fact that with mass production they got a lot more affordable.

However, since ordinary people rarely appear in the historical record, it has been difficult to trace their acquisitions and consumption.

So the researchers turned to look at the Old Bailey records to discover the trends. Specifically, they looked at thefts – what was being stolen, what did people have in their houses that thieves wanted to steal?

And fashions are there in the data – clothing , for example, accounts for about half the thefts. Sleeves and buckles, appear in the earlier records, but they stop being stolen as they go out of fashion, – then it is underwear and umbrellas which begin to be stolen. Clearly it was easy to sell on fashionable items, and some thieves were even apprehended wearing the fashionable items themselves.

Thieves stole anything and everything – sometimes whole houses were ransacked – large heavy good like mirrors and beds, as well as smaller items linen, clothing etc are to be found in the court records.

Sara and her colleagues looked at things that, over time, moved down the social scale, such as watches which became cheaper with the advent of silver plating.

Table linen was taken, because there was a good resale market, and as time wore on, more of such items were taken from those down the social scale – but at the same time the goods stolen from richer people became better quality (eg damask). The rich are differentiating what they own, it is elite consumption.

Stockings are a good example – they were often stolen – initially the rich had silk stockings, and worsted stockings were worn by poorer people. Then cotton stockings became fashionable (as cotton began to be imported), and they were bought by everyone, i.e. we see the democratisation of fashion. However, differentiation remains important and the rich continue to be the only people with silk stockings , which become even more expensive.

The Old Bailey records reflect consumption in London – but Is it only London where we see these trends? The metropolis is the centre of consumption,people are wealthier. However, fashion trends usually move from the metropolis to the regions and he researchers believe that the records can be seen as representative of the country as a whole.

At the time, the victim of a theft had to get hold of the perpetrator to take them to court for prosecution, so it was thought that only the wealthy, whose very valuable goods had been stolen would take the trouble to track down perpetrators and take them to court. However,about half the cases involve ordinary people (though it must be said that the theft of an Archbiship’s silverware, gets a fuller write up than the theft of a working man’s stockings!

The researchers’ main findings are:

- Eventually the working classes did have more goods, and people did want to engage in new forms of consumption – this is particularly evident in domestic comfort – curtains, better lighting, mirrors, feather beds – these goods were moving further down the classes, and people were prepared to pay more for better quality (eg feather matresses)

- London people seem to be sharing some of the democratisation of consumption, the gains of industrialisation but further afield eg skilled workers in Derbyshire in the 1840s may have had some of the goods, but they certainly didn’t have decent table linens and many families found it difficult to feed themselves and their children, certainly couldn’t go out and by feather beds.

- Mass produced cotton goods show up more and more in the inventories, and people seem to be prepared to pay more for them, because they had bright patterns – this is something new and desirable .

- Several factors affect consumption: price, desirability (eg feather beds for a good nights sleep), fashion and differentiation between the classes.

Music: Haydn’s String Quartet in G major, Op. 54, no. 1 performed by Malboro Music, available on the royalty free site MusOpen

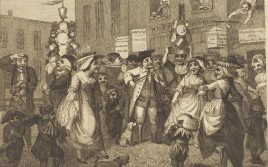

Picture: Willam Blake/Samuel Collings: May Day in London 1784

Subscribe with…