Transcript

Disaster and emergency management expert, Samantha Ridler, explores the beginning of modern seismology .

The earth has, since it creation been convulsed by earthquakes. But mankind has only relatively recently come to study them in a scientific manner. And much of this is thanks to an Englishman called John Milne.

It is perhaps surprising that a man born in Liverpool in the 1850 is considered by some as the ‘Father’ of seismology. After all the UK experiences very few earthquakes that are of a scale even noticeable by residents. The majority of earthquakes that the UK does experience are often out in the North Sea.

However John Milne studied Geology and Mining in the UK and was sent to Japan to teach about these subject, to the Japanese that had only a few decades earlier been forced from seclusion to open up to the rest of the world by the US.

Now Japan is very different to the UK in it’s Geology. Japan is part of the Pacific ring of fire and sits on top of the junction of 4 tectonic plates pushing and grinding against each other, which means it quite regularly experiences earthquakes of a moderate to severe nature. However at the time nobody knew about ‘Tectonic plates’ – the Japanese superstitiously believed the reason they experienced so many earthquakes, was that beneath Japan there was a large Catfish (or Namazu in Japanese) and this huge catfish was pinned down by a god called Kashima – whenever the god wasn’t watching or neglected his duties this catfish would wriggle and thrash and it was this wriggling and thrashing that caused the earth to shake.

So John Milne who arrived in Japan in 1876 to teach about geology, would not have been there long before he noticed the earthquakes and decided to study them.

It must have been a very exciting time to be in Japan because in that period Japan was experiencing rapid change. The majority of men and women still wore Kimonos, there were still some Samurai wearing swords and some married Japanese women would still paint their teeth black. There was rapid development with western railroads being built, traditional wooden housing being cleared for large masonry structures and western influences creeping into a place long seeped in tradition.

In 1880 a moderate earthquake shook Yokohama – a seaport town not far from Tokyo and populated by many westerners. And it was after this quake that John Milne called together a meeting of the Japanese Seismological Society the first such society in the world – and as no ‘science of seismology’ existed at the time, consisted of a mix of scientist, engineer and amateurs. Their first task was to try and create a measurement device for earthquakes. At the time the European scales for assessing earthquake size was based on damage and cracking to masonry structures, but in Japan, despite the rapid growth, there were relatively few of these – Japanese traditional wood housing would either wobble and stay upright( with little damage), or be completely flattened providing few degrees of variation to scale earthquake size.

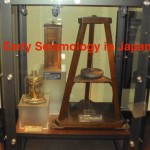

The seismographic device created was a collaborative effort between Milne and two others, Ewing and Grey. It used a Horizontal pendulum to detect shifts in the earth which is still a concept used in the core of many seismographs today.

The seismographic device created was a collaborative effort between Milne and two others, Ewing and Grey. It used a Horizontal pendulum to detect shifts in the earth which is still a concept used in the core of many seismographs today.

Although Japan has the longest written record of Earthquakes (due to it’s temples keeping records of such events), no centralised system for monitoring existed. If you felt an earthquake in your village, you would not know where it’s epicenter was or if people in other villages had experience the same earthquake to a greater or lesser extent than yourself.

John said he had ‘Earthquakes for breakfast, lunch and supper’ in Japan, and this gave him plenty of opportunity both to refine the seismograph further to make a more mobile device to distribute to locations across Japan and to establish the world’s first seismic network recording and centralising the data for Japan’s quakes

From his work with seismographs John Milne theorised in 1883 that ‘Terra Firma’ was less ‘firm’ than previously believed and that the crust of the earth was in constant motion – an idea well ahead of its time, as plate tectonics only became accepted in late 1950.

In 1891 the Great Nobi Earthquake occurred in Owari province sending shock waves across the country and causing more than 7000 deaths. It was while inspecting this damage that John Milne gathered evidence to show that, as he suspected, western brick structures where not suitable for seismic countries such as Japan. This was a very controversial point at the time as many western architects had been sent to Japan to replace it’s ‘primitive’ wood building with ‘modern’ brick and concrete buildings. Architects such as Josiah Condor, who when he inspected the damage the earthquakes had caused on a newly built brick mill blamed poor bricklaying by the Japanese.. Yet the survivors told Milne how the bricks had shaken free of their mortar and become like missiles killing many people which made him an ardent advocate of building more seismic safe structure.

John Milne was awarded many accolades for his work in Japan such an Order of the Rising Sun by the Japanese emperor. Yet In 1895 John Milne left Japan with his Japanese wife Tone after his lab was burnt down by arsonists, due to rising nationalism.

On returning to the UK, Milne moved to the Isle of Wight where he was able to have a seismic station sensitive enough to detect earthquakes from around the world and he also distributed seismographs to locations around the world, starting the creation of a global earthquake monitoring network. When John Milne Died in 31st July 1913 his death was reported as a full front pages story in UK newspaper’s such as the Daily Mirror who had come to call him ‘Earthquake Milne’ for his expertise.

If you go to the Isle of Wight you can find in the records office some of the burnt books Milne managed to rescue from his lab, and Carisbrook Castle has a seismograph and many of John’s photo’s from his life. In Japan too in the National Science Museum in Ueno Park they display many of John Milne’s seismographs and in 2013 to commemorate the 100 year memorial of John’s death the current Japanese Emperor Akihito visited the museum to see a special exhibitions on John Milne’s work

Back in Japan, Milne’s Japanese protégés became renowned seismologists in their own right. One former student of Milne’s called Fusakichi Omori became president of the Japanese Seismological Society and was for a time lauded for his expertise. He reassured the victims of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake that there would be not be another such earthquake for some time.

Mr Omori is well known in Japan among children in their history books but unfortunately not for his achievements. Mr Omori had a junior called Atkitsune Imamura, who in 1905 wrote a paper predicting a large earthquake in Tokyo could occur and cause large casualties.. Mr Omori however ridiculed Imamura’s work and ostracised him from the profession and even made Mr Imamura’s father apologise for his son’s claim.

Yet in 1923, while Mr Omori was at an Australian conference on Earthquakes, the large earthquake he said would never happen did occur, violently shaking Tokyo and it’s surrounding regions. The great Kanto earthquake killed over 100,000 people as it struck in the afternoon when many people were lighting fires to cook lunch in their wood homes meaning that immense fires started. Those who had survived the collapse of their homes where caught by the fire or drowned jumping in rivers trying to escape the flames. The highest number of casualties occurred near the downtown area of Ryogoku where people had fled to the open ground of an old army depot to escape the fires, only to be surrounded and incinerated by a Firestorm caused by the intense flames and winds.

In that area now, tucked behind the large sumo stadium, there is a dark and grim looking temple in which the ashes of those that died there, and of the later WW2 firebombings, are entombed. A nearby Memorial Hall has relics and photos of that terrible day.

Mr Omori, immediately returned from the conference on hearing about the quake. However he mysteriously became ill and came to die in a Tokyo hospital alongside the victims of the Earthquake that he denied would ever happen… And as for Mr Imamura, he then was given Omori’s job.

If you’d like to learn more about Japan’s Earthquakes I strongly recommend a book called Earthquake Nation and John Milne’s Autobiography

Tags: Earthquakes, Japan, John Milne, Seismology

Subscribe with…