Transcript

To begin at the beginning:

It is Spring, moonless night in the small town, starless and bible-black, the cobblestreets silent and the hunched, courters’-and- rabbits’ wood limping invisible down to the sloeblack, slow, black, crowblack, fishingboat-bobbing sea.

[Under Milk Wood]

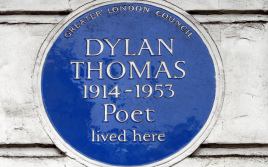

2014 is the centenary of the birth of the poet Dylan Thomas.

Scarlett MccGwire went to talk to Dr. Leo Mellor who writes and teaches about 20th century literature, particularly Anglo Welsh Literature and modernism, at Murray Edwards college Cambridge, where he is the Roma Gill Fellow in English.

She started by asking him what’s so special about Dylan Thomas that the centenary of his birth is being celebrated around the world?

Dr.Leo Mellor: I think it is to do with the way he brings a particular intensity to language. To the way he writes poems, that force or push language into moments of unexpected power and beauty and strangeness. He makes us see everyday things as strange again and he helps us see a beauty in things one would not normally consider beautiful.

Scarlett MccGwire: Like?

LM: I suppose you could think of his most famous radio play ‘Under Milk Wood’ and how he takes the average life of people in a little town there. Petty jealousy, their loves, their desires, and transforms them into something that is funny, beautiful and terribly moving – it’s just one night, in one little bible-black town.

The houses are blind as moles (though moles see fine to-night in the snouting, velvet dingles) or blind as Captain Cat there in the muffled middle by the pump and the town clock, the shops in mourning, the Welfare Hall in widows’ weeds. And all the people of the lulled and dumbfound town are sleeping now.

SM: Do you think he captures Wales?

LM: He captures a certain part of Wales but he also turns Wales into a place that is shaped by Dylan Thomas’s way of looking, thinking and feeling about things. This is not reportage, this is not the lives of people as lived in the 1930’s and 40’s in his formulation of ‘South Wets Wales’ and Swansea. He takes things from an area and he transforms them.

SM: Under Milk Wood is celebrated around the English-speaking world, so it’s much bigger than Wales isn’t it?

LM: Yes, because it’s a way of using radio, using a medium, where you don’t get to see anything. You get to see, in your mind’s eye, the characters who are constructed through how they speak and how they describe other people, and sound effects. So, it’s a play that is apparently about a small seaside town in west Wales, but uses a medium to do something quite incredible.

SM: He is most famous for Under Milk Wood, but also there are poems.

LM: It is important for us to remember how long his career was. He died age 39, but he was writing poems as a teenager, and these are not adolescent works, these are published in the Volume 18 Poems and they are amazingly good. I will read the first stanza of the first poem from the 18 poems I see the boys of summer

I see the boys of summer in their ruin

Lay the gold tithings barren,

Setting no store by harvest, freeze the soils;

There in their heat the winter floods

Of frozen loves they fetch their girls,

And drown the cargoed apples in their tides.

These boys of light are curdlers in their folly,

Sour the boiling honey;

The jacks of frost they finger in the hives;

There in the sun the frigid threads

Of doubt and dark they feed their nerves;

the signal moon is zero in their voids.

I see the summer children in their mothers

Split up the brawned womb’s weathers,

Divide the night and day with fairy thumbs;

There in the deep with quartered shades

Of sun and moon they paint their dams

As sunlight paints the shelling of their heads.

I see that from these boys shall men of nothing

Stature by seedy shifting,

Or lame the air with leaping from its heats;

There from their hearts the dogdayed pulse

Of love and light bursts in their throats.

O see the pulse of summer in the ice.

II

But seasons must be challenged or they totter

Into a chiming quarter

Where, punctual as death, we ring the stars;

There in his night, the black-tongued bells

The sleepy man of winter pulls,

Nor blows back moon-and midnight as she blows.

We are the dark deniers, let us summon

Death from a summer woman,

A muscling life from lovers in their cramp,

From the fair dead who flush the sea

The bright-eyed worm on Davy’s lamp,

And from the planted womb the man of straw.

We summer boys in this four-winded spinning,

Green of the seaweeds’ iron,

Hold up the noisy sea and drop her birds,

Pick the world’s ball of wave and froth

To choke the deserts with her tides,

And comb the country gardens for a wreath.

In spring we cross our foreheads with the holly,

Heigh ho the blood and berry,

And nail the merry squires to the trees;

Here love’s damp muscle dries and dies,

Here break a kiss in no love’s quarry.

O see the poles of promise in the boys.

III

I see you boys of summer in your ruin.

Man in his maggot’s barren.

And boys are full and foreign in the pouch.

I am the man your father was.

We are the sons of flint and pitch.

O see the poles are kissing as they cross

SM: And Fern Hill, another one.

LM: Fern Hill is written right at the other end of his career, but yes it is a poem what uses this mythical quality of childhood, of looking back at childhood and of pastoral beauty. But it’s a pastoral beauty that is unsteady, its scared.

We can think of Thomas in many terms. He was a precocious poet, he burst on to the scene. He terrified London. He was a sensation. We can think of him as a war time poet – some of his best poems were written in the Second World War. We can think of him as a film maker, he worked as a screen writer from 1942 onwards for Strand Films. We can think of him as a short story writer, some of his best, strangest short stories in English were written by him in the 30’s. And then we can think of him in the late 40’s and early 50’s returning to these childhood scenes through ‘Under Milk Wood’, which of course was written right at the end of his life, but also poems such as Fern Hill.

Now as I was young and easy under the apple boughs

About the lilting house and happy as the grass was green,

The night above the dingle starry,

Time let me hail and climb

Golden in the heydays of his eyes,

And honoured among wagons I was prince of the apple towns

And once below a time I lordly had the trees and leaves

Trail with daisies and barley

Down the rivers of the windfall light.

And as I was green and carefree, famous among the barns

About the happy yard and singing as the farm was home,

In the sun that is young once only,

Time let me play and be

Golden in the mercy of his means,

And green and golden I was huntsman and herdsman, the calves

Sang to my horn, the foxes on the hills barked clear and cold,

And the sabbath rang slowly

In the pebbles of the holy streams.

All the sun long it was running, it was lovely, the hay

Fields high as the house, the tunes from the chimneys, it was air

And playing, lovely and watery

And fire green as grass.

And nightly under the simple stars

As I rode to sleep the owls were bearing the farm away,

All the moon long I heard, blessed among stables, the nightjars

Flying with the ricks, and the horses

Flashing into the dark.

And then to awake, and the farm, like a wanderer white

With the dew, come back, the cock on his shoulder: it was all

Shining, it was Adam and maiden,

The sky gathered again

And the sun grew round that very day.

So it must have been after the birth of the simple light

In the first, spinning place, the spellbound horses walking warm

Out of the whinnying green stable

On to the fields of praise.

And honoured among foxes and pheasants by the gay house

Under the new made clouds and happy as the heart was long,

In the sun born over and over,

I ran my heedless ways,

My wishes raced through the house high hay

And nothing I cared, at my sky blue trades, that time allows

In all his tuneful turning so few and such morning songs

Before the children green and golden

Follow him out of grace.

Nothing I cared, in the lamb white days, that time would take me

Up to the swallow thronged loft by the shadow of my hand,

In the moon that is always rising,

Nor that riding to sleep

I should hear him fly with the high fields

And wake to the farm forever fled from the childless land.

Oh as I was young and easy in the mercy of his means,

Time held me green and dying

Though I sang in my chains like the sea

These are poems that people return to again and again. He has never been out of print. But they are also poems that benefit from reading at different stages in your life because they start to mean different things and tell you different things. I think that would be, for me, one of the hallmarks of greatness. He not only survives re-readings he changes you by your re-reading of him.

SM: Do not go gentle into that good night is a poem that you found very personal?

LM: Yes, It’s a very powerful, very moving poem and it’s a poem that I read at my grandfather’s funeral. My grandfather, he was Welsh so I called him taid, and it’s a poem that is often read at funerals. There are good reasons for that. It’s a poem that makes us feel why and how it is inevitable.

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

SM: we don’t think of Dylan Thomas as a war poet, but you see his poems of the early 40s, when he was in London, as war poems?

LM: Yes, when I talk to my students about war poetry from the 20th century they return again and again to poets of the first world war especially Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen. But if one thinks of the second world war, Thomas is a significant poet, if not the significant poet, partly because the poems are powerful and extraordinary,but partly because he captures one of the terrifying and strange facts of the second world war, which is that you were in more danger as a civilian in London than if you were in the armed forces up until D-day and the invasion of Europe more people died in the bombing of London than died at Dunkirk.

Thomas spends most of the second world war in London and he works for Strand films, he writes short stories and he writes very powerful and moving letters especially to his friend Vern Watkins, about the experience of bombing and the strange sights he sees.

He also writes about the problem of mourning, the problem of mourning deaths in a war time and how he was uncomfortable with poets being co-opted into expressing sorrow and grief, and being told to make meanings from people being blown apart in the streets or in the houses where they lived. It was a time when the saying ‘ as safe as houses’ meant nothing.

This is a poem Dylan Thomas wrote in the 1941 after he saw a newspaper headline. The newspaper headline became the title of the poem,

Among those killed in the dawn raid was a man aged 100.

When the morning was waking over the war

He put on his clothes and stepped out and he died,

The locks yawned loose and a blast blew them wide,

He dropped where he loved on the burst pavement stone

And the funeral grains of the slaughtered floor.

Tell his street on its back he stopped a sun

And the craters of his eyes grew springshots and fire

When all the keys shot from the locks, and rang.

Dig no more for the chains of his grey-haired heart.

The heavenly ambulance drawn by a wound

Assembling waits for the spade’s ring on the cage.

O keep his bones away from the common cart,

The morning is flying on the wings of his age

And a hundred storks perch on the sun’s right hand.

SM: A possible problem for Dylan Thomas is that his poetry is sometimes over shadowed by the stories of his life, most of which appeared to be spent in pubs.

LM: There are are two sides to this, partly it is his own mythmaking – he was a larger than life personality and he conjured up stories about his own drinking, and his capacity to drink. There is a strand coming from him, there is also a strand of how we want our poets to live fast and die young, to behave badly, to get drunk and fall over. Thomas obviously drank and drank heavily at points, but no one could have written the poems he wrote and the stories, and the journalism and appeared on the radio so much if he was an alcoholic who spent all his time in pubs. He spent a lot of time in pubs as it was a way of meeting people and discussing poetry with his friends. And when he went home he would then write. He would write and then rewrite, he would then work on a poem until he was happy with it.

There have been tremendous exhibitions this year, held at the national library of Wales, with all his worksheets and archive material that has been lent from University of Buffalo. You can see how hard he works at a single line, how hard he works at a single phrase, how hard he works choosing the right word. This is not the action of a man who is a habitual drunk. This is the action of a man who wants to craft poetry.

SM: What do you think he’s got to say to us today. It is the centenary of his birth. He died early – half way through the last century. Is he still relevant?

LM: Yes, he shows that you can be a popular poet who is complex and does complex things. He shows you can have a wide, non-academic audience and deal with big troubling philosophical issues and he shows how you can make beauty out of the strangest things. I think this is an important lesson for anyone writing today.

SM: And he was popular even at the time? He is not just celebrated afterwards?

LM: He was very very popular at the time. Mainly from the 1940’s onwards where he publishes a collection ‘death and entrances’ but then after the war, especially after ‘Under Milk wood’. And he is, of course, popular across the world. I’ve been talking to Dylan Thomas Scholars from Finland, from France, from India.

He is someone who keeps on giving because you find there is a new collection out which has a lot of previously hidden material. Some of it very good, some of it ephemeral – but who could not be interested in a Dylan Thomas drinking song which has been recently found in his archive by a professor from Swansea.

He is a poet who can always be rediscovered, and when read, especially when first read by people in their teenage years, he gives this amazing electric galvanic shock to the system with the idea that poetry can do all of these things, can be this beautiful, this strange and this troubling. Because sometimes we want to take easy lessons from poets and from poems. One of the great things about Dylan Thomas is he gives us beauty, and he gives us moments of lyrical insight, but he doesn’t tell us that everything is going to be nice and that it is going to be ok – that is probably an important thing we can also learn.

- Transcript by Helena Charles

- Photo of plaque at Dylan Thomas’s home in London – 54 Delancey Street, Camden, NW1, by Simon Harriyott

Tags: Centenary of birth of Dylan Thomas, Do Not Go Gentle into that Good Night, Dylan Thomas, Fern Hill, I See the Boys of Summer, Under Milk Wood, Wales, War poems

Subscribe with…