Transcript

Change ringing is a way of ringing church bells, particular to England, which uses all the bells in a church tower, ringing them in rounds an ever-changing order. Despite using consecrated objects, change ringing has no liturgical or spiritual foundation. And, although bells are a kind of musical instrument, the structure of change ringing is based on strict mathematical patterns of permutation.

Katherine Hunt has been studying the practice for her Ph.D at the London Consortium. She spoke to Pod Academy about her research which looks at the emergence and reception of change-ringing in the seventeenth century.

Jo Barratt: Change ringing is a method of ringing church bells which is unique to England. The practice has changed little in 400 years. Katherine Hunt is writing a Ph.D at the London Consortium about the invention and reception of change ringing in seventeenth-century England.

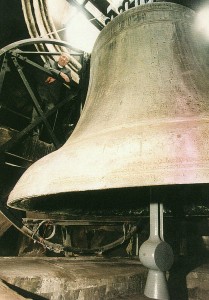

I wound my way up a spiral staircase to met her in the bell tower of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. But first, we jump across the river to listen to the 12 bells of Southwark Cathedral.

Katherine Hunt: They have just started to ring now. They’ve started off ringing all twelve bells from the highest note to the lowest. They are just ringing them in rounds, and you can hear that there are 12 bells involved. It’s quite easy to work out that there are 12 separate sounds.

There is a hum building up as the sound of each bell expands and continues to ring once the bell has been struck. The more rounds the ringers ring, the bigger this hum becomes.

They start to vary the order in which the 12 bells are rung and the sounds become more disjointed and they start sounding less regular and less ordered. It becomes much more difficult to work out how many bells there are because they are no longer in this neat, Russian doll-style order. They start getting jumbled up but in a way that you can still feel that you can hear the original order in which they started to be rung.

It’s a very very familiar sound but at the same time listening to it closely it’s very disordered and very jangly and it’s difficult to discern a melody in it, because there isn’t one, and it’s difficult to see where this music or this sound is going and whether or not this is in fact music at all. There are points in the ringing where it sounds as if the bells are about to return to a kind of order. That they are beginning to approach that order that we heard at the beginning but then again resolve themselves into this disorder.

We end it with the bells ringing from the highest note to the lowest, again it becomes far more easy to work out that there are 12 bells ringing. And that set of changes has been resolved.

Change ringing is a way of ringing church bells which is unique to England and is a very English activity. It has been done here since the seventeenth century. The bells in a church tower are rung in rounds. Every bell in the tower must be rung and the order in which they are rung must never be repeated. There must be constant variation in the order of the rounds. My Ph.D is researching the history of change ringing and its reception in the seventeenth century and I am really interested in it because it is such an unusual practice. Its form is related to these quite complicated ideas of mathematical permutation but at the same time it is a sound that is very familiar. A sound I think people know very well, but maybe don’t listen to very carefully. When you listen I think the complicated form that underlies it and this constant variation – order and and disorder at the same time – really comes though when you are listening to it closely. I’m looking at how it was invented, at who did it at the time and what their motivations were. Also I’m interested in how people heard it at the time and how people hear this really unusual sound now.

Change ringing is a way of ringing church bells which is unique to England and is a very English activity. It has been done here since the seventeenth century. The bells in a church tower are rung in rounds. Every bell in the tower must be rung and the order in which they are rung must never be repeated. There must be constant variation in the order of the rounds. My Ph.D is researching the history of change ringing and its reception in the seventeenth century and I am really interested in it because it is such an unusual practice. Its form is related to these quite complicated ideas of mathematical permutation but at the same time it is a sound that is very familiar. A sound I think people know very well, but maybe don’t listen to very carefully. When you listen I think the complicated form that underlies it and this constant variation – order and and disorder at the same time – really comes though when you are listening to it closely. I’m looking at how it was invented, at who did it at the time and what their motivations were. Also I’m interested in how people heard it at the time and how people hear this really unusual sound now.

JB: Could we start by you telling us where bell ringing began. What was it before the seventeenth century?

KH: The English have always been very fond of their bells and they were very proud to be known as ‘the ringing isle’. This name for England became certainly more pronounced in the seventeenth century. Before the Reformation, bells in churches had lots of different uses. They would obviously call people to church, but they would warn of invasion, they would mark weddings, when people died. They had a lot of different uses which regulated religious time, secular time and the general life of the community. Different bells had different uses and they could be rung all together, or individual bells could be rung and people would understand the meaning of a particular bell being run in a particular way.

JB: Were these community specific sounds. Would somebody in London and, say, Northumberland, be aware of the meanings of the same bells?

KH: I think people certainly developed a hearing for their own parish church bells, there are similarities, so people would probably recognise the certain times of day at which a particular bell might be rung and warning bells might have quite an insistent sound. There were certain types of tolling that were done at the death of a person which also might have been familiar. Certainly the sound of your own parish bell was something people felt that they knew.

JB: How did this evolve in to change ringing?

KH: After the Reformation there were many fewer liturgical uses for the bells. Certainly prayer times that were related to the monastic calendar were no longer applicable because the monasteries were no longer in use. Lots of the liturgical uses of the bells were now curtailed but I think in England, and in other Protestant countries, people were particularity fond of their bells. There are lots examples of parishes hiding their bells, of burying them or pretending that they didn’t have then so that they would not get found out by the authorities and taken away because they were no longer needed. They are one of the most extraordinary survivals of the Reformation because lots of other moveable objects were destroyed or altered and bell metal is really valuable. There were several injunctions put out by Henry and Edward about needing bell metal for the money, but bells did survive and in quite large numbers. I think that it is partly this that led to the rise of change ringing. The foundation of change ringing is not really known about but I think that an enthusiasm for ringing bells – lots of people in the bell tower all together often drinking quite a lot for beer — developed from ringing rounds as we heard at the beginning, with the ringing of the Southwark Cathedral bells, just ringing bells in order from the highest note to the lowest. I think that developed into more sophisticated ways of ringing them. Reformation survival of bells and a real popular enthusiasm for ringing was what allowed change ringing to begin.

Change ringing is the very specific way of ringing bells in which all of the bells of the church tower are rung in rounds but the order in which they are run must never be repeated. It depends on constant variation. If there are 5 bells in a tower, they might start off 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, which is those nice orderly rounds which we heard in the Southwark Cathedral ringing. But in the next round they might be rung in the order 2, 1, 3, 4, 5 and then maybe 2, 1, 4, 3, 5. In the seventeenth century bell ringers figured out a way to get though all the possible orders in which this number of bells could be rung and this is a mathematical calculation called the factorial which is represented by the number and then an exclamation mark. The numbers that this factorial can come up with is something which was a great source of amazement and wonder to bell-ringers. The factorial is formed by, for example for 5 bells, is 5 x 4 x 3 x 2 x 1 so the number of changes it is possible to ring for 5 bells is 120. These numbers escalate rapidly so that for 7 bells the number of changes possible is 5,040 and for 12 bells it is 479,000,000,1600. Change ringing in its most formal sense attempts to find ways of getting though all of these possible changes whilst never repeating an order but also using specific rules which determine the order in which the changes may be done. The rules have changed quite a lot between then and now but one of the rules that stays is that a bell cannot be rung last in a row and then first in the immediate following row. This is kind of a practical consideration because there would not be time for the bell to get back in to a good position to be rung.

JB: It it a skilful thing?

KH: I think the best analogy is maybe to that of an 8-man rowing crew in which everybody is doing the same thing (although rowers are doing it at the same time whereas bell-ringing is syncopated). It’s extremely skilful making the rounds ring evenly, making your bell ring in the right way. Also, just following these methods which are based on these complicated mathematical permutation in which the idea is to make ones way though the whole set of possible changes its very complicated. Ringers have to internalise the methods and feel their way though them and know their way though the different types of changes that can be made and understand the patters of them to be able to ring them.

JB: As a way of maybe understanding that, if we walk toward the centre of the bell tower there is an award here – the National Twelve-Bell Striking Contest, of which the bell ringers here were the winners in 2009 – how would a bell-ringing competition work and how would it be judged?

KH: For the Twelve-Bell Striking Contest there are bands of ringers and they just do a part of a peal. They would be judged according to the equal timing of their striking. In the eighteenth century people started talking about true and false peels. A true peel is when you had successfully gone though the method in the correct way and a false peel was when you made a mistake and bells were jumbled up or not in the right order. Particularly that you had been trying to follow a particular method. But something had gone wrong. It is according to those principles still. Equality and smoothness of the intervals, but also successfully doing the method in the correct way.

The idea with change ringing is that the change ringers should become a single instrument and certainly in the seventeenth century this was the goal. Fabian Stedman, who was one of the first writers on change ringing, and a ringer himself, this is one of the things he emphasises in Campanologia (1677) and describes how there could be an even compass between each bell. The goal was not necessarily to impose a style as a violinist may have a style but to indifferently make the bells sound as good as they could.

JB: So it’s close to music, but to describe it as music would probably not be correct?

KH: Lots of change ringers, especially at the beginning, did describe it as music, but its position as music has always been quite contentious. It sounds musical but it doesn’t have many of the things that we associate with music like melody, harmony or refrain. Stedman talks about its invention being mathematical but there is a sense in which it is musical because it is sort of unclear what else it is. People are doing this activity which they talk about in terms of music. They also talk about it in terms of exercise and in terms of being something that is good for the body and strengthens the mind and the body and is healthy. Also, as something that is a leisure pursuit. Something that you can do in your spare time. It is described as a very English pursuit, as one that is good for the body, works the mind and is this good meeting point between the theoretical and the practical. The ‘speculative and the practic’ is how Stedman describes it.

JB: So like a cross between a Sudoku puzzle, going to the gym and going to the pub.

KH: Exactly. Possibly at the same time being in a concert hall. Sudoku is exactly what it is. Every item must be present in each row. No preference is given to a particular instrument or a given sound.

JB: It has a complicated relationship to music and also to maths?

KH: I would agree. There there is a branch of mathematics which it is related to called group theory, which was codified in the nineteenth century. Change ringing is quite a simple form of group theory but it can be explained using these principles. Its all about sets and co-sets and the ways in which composers of methods of change ringing manage to make their way through all of the possible changes uses exactly the principles of group theory. There are similarities between the form of change ringing and serialism in the twentieth century. People like Schoenberg and Webern and later people like Boulez and others. They are restrictive but quite complete forms of composition and, I think, the most similar in music to what change ringing is.

JB: What are we listening to now?

KH: Well this is a method calling the 20 all over which was included in Fabian Stedman’s Campanologia. It’s been recreated and rung by the bell ringers of St. Bartholomew the Great at Smithfields. There are about 5 bells there that date form about 1510 and they are the only surviving pre-Reformation bells in the City of London.

JB: What we are hearing is exactly what somebody in the seventeenth century would be hearing?

KH: Pretty much. Some of the mechanisms have changed since then but change ringing provides one of the most continuous sound that it is possible to have. The same instruments, the bells, being played in exactly the same way in exactly the same place. It’s a kind of remarkable aural survival, there are not many sounds that can claim to have such an incredible aural history. You can hear the sounds much more clearly than in the Southwark example. There are only 5 bells and they are quite a lot smaller. They sound tinnier because they are very old and tinkling rather than the richer sound we got from the Southwark bells. Because of these bells and because there are only 5 of them I think it is easier to make out the changes. Sometimes in the Southwark Cathedral bell example that hum that builds up means it can be difficult to pick out individual bells. With the St Bartholomew the Great bells it is much easier to hear these individual sounds. As it is this historical sound it’s maybe a good time to think about how people may have heard these sounds when they first listened to them in the seventeenth century.

Each of these bells would have had an individual meaning and different syncopations of them would have had different meanings. Now they are all being rung together in this new sound and I don’t know what people would have made of it.

JB: What kind of people were into bell ringing.

KH: During the seventeenth century all different sorts of people seemed to have done it. It’s an activity which is quite difficult to uncover because the sound of bells is something that people heard all the time in all sorts of different ways and people don’t tend to write about things that happen all the time. There are certainly some societies that were founded in the seventeenth century. One of which, the Ancient Society of College Youths is still going today. They seemed to have lots of different sorts of members. The Ancient Society of College Youths for example had quite a lot of gentry, clergymen, esquires, admirals as members. People who were really into it but certainly not the type of people who would have been paid to ring bells for church services. At the same time there were other societies with a lower class of people. Apprentices, tradesmen. Along side this, especially in country parishes, the people who would always have rung the bells for fun, continued to do it. You have a real mixture I think of the same sorts of people, of people doing it as a leisure activity, and people whose involvement is not particularly clear. These upper-class ringers seem to tail off a little bit as the seventeenth century ended but I think that’s the way that change ringing has evolved. People who do change ringing now come from all sorts of walks of life.

Change ringing is still a very vibrant activity in this country and change ringers have done an incredible job of researching and writing their own history. Even in the seventeenth century, the very first books on the subject talk about the sudden formation of this new activity and they are trying to write its own history and talk about how suddenly and quickly it grew and how strongly it’s been taken into the heart of the country. It obviously still holds this great continuity with how the activity started in the seventeenth century.

JB: In this programme you heard the twelve bells of Southwark Cathedral, rung by the Southwark Cathedral Society of Bellringers and recorded in 2011 by Duncan Whitley.

And the five sixteenth-century bells of St Bartholomew the Great, Smithfield, London, rung in 2010 by Romee Day, Christine Stratford, Pauline Dingley, Paul Norman and James Ingham.

Thanks to Dr. Chris Marsh of Queens University Belfast, from whose publication, Music and Society in Early Modern England (Cambridge UP, 2010) the recording of ‘The Twenty All Over’ was taken. Also to Simon Carter, Collections Manager at St. Paul’s Cathedral.

If you enjoyed this Pod Academy programme, be sure to listen to the other podcasts available in our arts and culture faculty.

Presented and produced for Pod Academy by Jo Barratt

Notes

Central Council of Church Bell Ringers represents all who ring bells in the English tradition with rope and wheel. It has over 60 affiliated societies around England and Wales, and one or two in other parts of the world. Its committees include a Peal Records Committee which keeps a record of peals – in particular those of record length. It also runs courses on ringing.

The Ringing Foundation has information on learning to ring.

One hundred year old Ringing World is a weekly journal for bell ringers, and includes a shop with gifts for bell ringers.

A link for those interested in the history of Southwark Cathedral bells, which are heard at the beginning of the podcast.

The Ancient Society of College Youths: the website of the society, founded in 1637.

St Bartholomew the Great, Smithfield, whose bells are heard in the podcast.

Shotgun Sounds: a website featuring sound and video work by Duncan Whitley who recorded the Southwark bells.

Tags: Ancient Society of College Youths, Campanologia, Change Ringing, Fabian Stedman, Katherine Hunt, Maths, Music, National Twelve-Bell Striking Contest, Noise, Reformation, Religion, Southwark Cathedral, St Pauls, St. Bartholomew the Great, The London Consortium

I thank Katherine Hunt and Jo Barratt for this history. I grew up with a father who had been change ringing since a teenager until the day of his death on J/une 12, 1982, having experienced heart failure on his way to Leicester Cathedral on June 9 to ring in the new Assize session as was customary.` W. Ernest Rawson was a member of the Leicester Police Guild of Bell Ringers for almost fifty years, though he was never a policeman. My mother considered herself a bell widow, but we often accompanied my father around the country on his bell-ringing excursions. That way I managed to see practically every cathedral and most major churches in England.

When I moved to the States for postgraduate study (and never returned), my parents visited us in 1976, the two hundredth anniversary of the American revolution. There are only ten bell towers for change ringing in the whole of New England. My father rang at Hingham near Boston, Groton, and Washington Cathedral in celebration of the anniversary.

I remember my father, who was mathematically inclined, poring over the graphs in which he memorized the exact timing of his bell. Each Friday I would walk to our local newsagent to get my father’s Ringing World. It was not until after his death that we discovered he’d developed, with the help of Police Chief’s Harold Poole’s peal books, a meticulous record of all full (half or quarter didn’t count) successful peals that he’d rung. In those days, one mistake would stop a peal. With Ernie Morris he shared the distinction of having achieved at least 1,000 full peals in his lifetime. His records were given to the Ringing Guild and a memorial plaque was placed in the belfry of Leicester cathedral.

Do people know that bells are rung upside down, so that they have to be rung up and rung down before and after every session? What has always amazed me (and I would like to know how it works), with every blow of the clapper, the bell turns a full circle from the handstroke “up” position to the backstroke “up” position and vice versa. How do the ringers manage to control the timing of the second ring?

In his later years, my father began to teach other young ringers. What I learned from him and practiced in my own teaching career, was to take advantage of new ways of teaching that would speed up the process for our students. What I miss most about England, is hearing bell practice on a Wednesday evening across the miles of countryside, and then hearing them peal for Sunday services.