Transcript

“Biography is actually a quest for lives that speak to us” said biographer Hermione Lee.

So what is the role of the biopic in contemporary film culture? What is it that we are looking for in the increasingly popular ‘biopic’ genre – films like Selma, Diana, Saving Mr Banks, 12 Years a Slave or The Wolf of Wall Street that claim to be based on real life events and aim to depict episodes in the lives of their protagonists?

Pod Academy’s film specialist, Esther Gaytan Fuertes, went to talk to Tom Brown and Belen Vidal, two lecturers in Film Studies at King’s College London, about their recent book, The Biopic in Contemporary Film Culture, to find out more about this genre.

Esther started by asking them if they felt the biopic was a neglected area in Film Studies.

Belen Vidal: Well, yes and no – it’s been studied but yes, perhaps it hasn’t been studied enough. The thing is that the biopic as a genre has always been there, I mean, it goes back to the beginning of film history.

But the biopic has also cropped up as part of other genres and that’s the way it’s been looked at mainly by scholars – as biopics that were part of the musical genre, or gangster films or Westerns… All those genres would have biographical elements or would occasionally do stories that are based on real characters, or real lives or people that existed. So, in a way, there’s been forming an idea of the biopic throughout film history as part of the popular genres, but the truth is that when Tom and I came into this project we also did it because we were interested that, in all this time, basically what we have is only two books, which are two excellent starting points to study the biopic, but it seemed very little considering the popularity of the genre.

It’s worth mentioning that the first book that took the genre seriously or did a kind of serious comprehensive approach was George Custen’s book called Bio/pics: How Hollywood constructed public history – this was a book on the classical biopic, mostly films made in the 30s and 40s, and it focused on Hollywood. After that, recently we’ve had a book coming out by Dennis Bingham [Whose Lives are they Anyway?] about the biopic in contemporary film culture. And again this is a book that tackles the modern biopic – the biopic since the post war period and up to the contemporary moment. But, again, it’s very heavily leaned towards the English language. So we thought, why not doing a kind of more reviewing of the biopic in the last twenty years especially and how also the genre has spread, has become more visible internationally? Because what Tom and I were struck by was the huge number of films coming from very different national cinemas all marketing themselves as biographical films and many of them very often being immensely popular. If we think about La Môme (that was called La Vie en Rose) here, a French film about a French singer, Edith Piaf, making it all the way to the Oscars, all the way up to kind of the big time in Hollywood and it’s distributed all over the world. What were the conditions that were creating this appetite for biographical narratives and how these films are now becoming much more visible not only from Hollywood but from all over the world? So we wanted to study this phenomenon and say something about the biopic in contemporary film culture and that’s what the book is about.

What approach do you adopt in your book to study the biopic?

Belen Vidal: What we are really interested also is in the narrative structures, in the tropes that recur time and again. Is there such a thing as the poetics of the contemporary biopic? Is there such a thing as a kind of certain structures that are being used and reused time and again, new genres forming…? That’s what we were interested in when we were looking at the different chapters and bringing the work together and trying to find the different points in common between chapters that very often would tackle cycles and bodies of films from very different national cinemas. So in the book, for instance, there is a chapter concentrating on the South Korean film industry and the boom of the biopic there. Another chapter on Indian cinema, Bollywood cinema and the biopic. Another chapter on French cinema… Also contemporary American cinema, but biopics coming from all over the world. So we were wondering, why this boom of biopics now (meaning in the last 20 years)? And what kind of lines can we find for the study of the biopic without it becoming excessively fragmented, just having more and more examples, just what are the main lines of study, what are the main questions these films are asking?

Esther also asked Tom Brown and Belen Vidal if a biopic can properly represent the life of a real person, and whether we can distinguish between good and bad biopics.

Tom Brown: I’ll let Belen kick of with the question of ‘properly represent’ the life of a real person and I’ll come to the good and bad because I’m interested in that particular question.

Belen Vidal: Again this is a very intriguing question because what’s ‘properly’ representing the life of a real person? Obviously this question goes back all the way to biographic studies and the different styles of writing biography: from the encyclopedic, classical biographies to the kind of more modern biographies that have tended to concentrate more on moments in time. I’d definitely say that there is no proper way but I’d subscribe to what Hermione Lee, an illustrious biographer, said about the genre: “Biography is actually a quest for lives that speak to us”. This is to say, it’s really as important the capturing of the essence of the person, of the character or the live of the person as it is why it matters to us now and why it should matter to us. Why this film is fascinating and it makes for fascinating story here and now. This is also what biography is about: about what we can learn not only from a period in history or about the life of an individual person but about our own relationship, if we want, to the past and present.

So the question of how best represent the live of a real person is fraught question because what we can say is there have been modes of writing and modes of filming about real lives. We can go all the way back to Sigmund Freud and when he was researching about the live of Leonardo da Vinci and produced a biography that actually was heavily criticised by his contemporaries as being completely inaccurate. But what Freud was looking for was not exactly an accurate biography but for symptoms or little clues in the childhood of Leonardo that would give you a sense of the man that he would become later and the great artist he would become. And this is a model that really endures in contemporary film-making as well as in classical film-making. We’ve looked at it as the teleological model or the self-fulfilling narrative: going back to the beginning of a narrative, going back to the childhood of the person only to find exactly the clues that make sense for what we know the person will become. In that sense it produces a completely artificial or contrived narrative because it’s always conditioned by what we know this person will become great for. So the narrative becomes subordinated to that, it’s shaped by that knowledge. So we were very interested about how that knowledge can become very conventional and, in a way, very predictable.

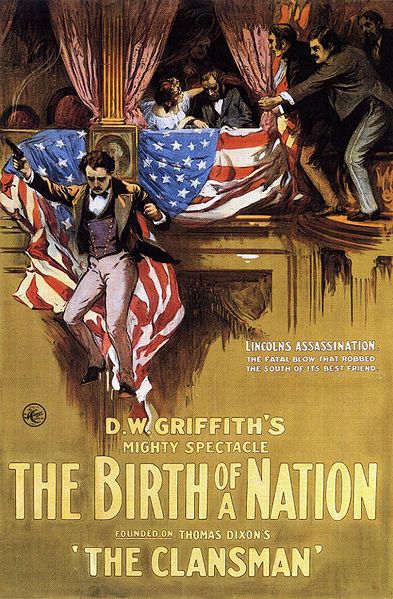

And it’s fascinating that, when we were looking at interviews with film directors, most of them expressed real resistance to the genre or mistrust of the genre. Someone like Todd Haynes, for instance, has expressed disdain for the genre. Even if he’s made biopics like his most recent, I’m Not There, he’s said about the genre that it’s a formula and he said: ‘It’s a formula even more than other film genres, because whatever the life is, it has to fit into this one package’. This is a quotation, actually, from an interview, it’s something he’s said. Other people like Jane Campion, when asked about films like Bright Star – the film about John Keats, the poet, that Jane Campion made in 2010 – or Steven Spielberg, when asked about Lincoln, basically he would say ‘this is not a biopic’ – Jane Campion also would insist, when asked about Bright Star, ‘this is not a biopic’. Because they see the biopic as this very conventional cradle-to-grave formula, a film that has to cover the whole life of the character, the whole life of the person, whereas the kind of film-making they are interested in is not this kind of classical film-making. The thing is that, when we were doing our research, we found that actually there were very very few films that you could say they went from cradle to grave, that went from birth to death. This is a format that is actually not amenable for film-making. There is one example that we found, the Abraham Lincoln made by…

Tom Brown: D.W. Griffith, yes. But yes, that’s the only Lincoln biopic… (because I’m doing some further research on Abraham Lincoln biopics), it’s the only one that follows him from the cradle to the grave and the only one of the ones you’ve seen that we’ve been able to identify kind of starting with the baby subject. And even Griffith’s Lincoln has the baby but then it jumps to him as a young man played by Walter Houston who plays Lincoln for the rest of the film and goes on from there. So this kind of gradual move through stages from birth to death it’s not what the films do. Their narrative, their engagement with a range of other genres is more complex than that, isn’t it? They’re drawing on Westerns, or they’re drawing on musicals or they’re drawing on a range of other forms to create the structures that edit and flow as life.[1]

Belen Vidal: Exactly. And also their use of narrative figures like condensing or summarising or putting together the research about different moments in the life of a person – just putting it together in one event or one anecdote that contains basically the point that they want to make.

More transcript to follow……

Tags: Biographical films, Biopic, Cultural studies, Film studies

Subscribe with…