Transcript

This podcast is the second in our series on new concert music. New music can be unfamiliar and challenging – this series, written and presented by composer Arthur Keegan-Bole, is designed to present new music in a non-scary way or at least to explain that composers are making logical music – not trying to make weird, ‘difficult’ music to confound the listener.

The sublime music in this podcast, I will Pour Out My Spirit, ‘Effundum Spiritum Meum’, is a newly composed piece by Benedict Todd relating to the lost sounds of a ninth century Iberian liturgy. It was composed as part of Bristol University’s exciting Old Hispanic Office project.

Now over to Arthur to introduce this podcast…….

Arthur Keegan-Bole: Hello, you’re listening to I will Pour Out My Spirit, ‘Effundum Spritum Meum’, a podcast about how a newly composed piece of music relates to the lost sounds of a unique liturgy called the Old Hispanic Office which was first sung on the Iberian Peninsula before the 9th Century.

Hold on, stay there, stay with me. It’s not as niche-an-episode as you might think. No working knowledge of early medieval Spanish church-going is necessary… I promise.

My name is Arthur Keegan-Bole and I’m a composer the purpose of these podcasts is to explain ways that new music relates to music of the past. In this episode we are going way back to music first written down in the Tenth Century and how musicological research into this repertoire has directly inspired the piece of music you’re hearing.

The piece was written in 2015 by Benedict Todd (hello Benedict!). You’ll hear much more from him as we discuss then interaction of music and text and how the medieval notation greatly influenced his piece of music.

We’ll also hear from Dr Emma Hornby who leads the cross-disciplinary research team investigating the Old Hispanic Office and whose project spawned the call for new works. All this to come, but for now lets just enjoy this really good bit…

Before getting onto the new stuff, lets explore what the Old Hispanic Office actually is by first hearing what it is not. It’s not the familiar sound of Gregorian chant which forms the Roman Catholic liturgy and which could be said is the genesis of the entire Western tradition.

Emma Hornby: The old hispanic office is what was sung across most of Iberia until about the year 1080 when there was a big suppression of it by the pope.

[AKB]

This is Dr Emma Hornby, an early music specialist and reader in music at the University of Bristol. She heads up the Old Hispanic Office project.

[EH]

It’s a Western, Latin, Christian church but it’s not the Roman liturgy – that’s the Gregorian chant.

[AKB]

Okay, so brass tacks – ‘liturgy’ we’re talking about how the church goes about structuring services through the day

[EH]

Exactly so, yes. So the Office is the way that monks and clerics go around and around singing the Psalms, singing chants, readings, prayers and the shape of how they do that in medieval Iberia was unique, different from anywhere else in western Europe. It’s not just that the melodies are different and that the texts are different, it’s that the whole shape of the liturgy is different, so you get through the day in different ways and it’s almost entirely un-studied.

[AKB]

Interesting stuff to an early musicologist or historian maybe but what has this got to do with composers? That stems from Emma’s novel response to a problem with the sources for this music – the notation does not give enough information for the sound to be fully recreated. We can’t know what it sounded like.

[EH]

As I was planning this research I kept coming against the sticking point that I want to share my research with the widest possible audience and that’s not just… I mean, there aren’t many other scholars interested in Old Hispanic chant before you start. There aren’t even that many scholars interested in Gregorian chant, it’s a niche interest. But I think the research we’re doing has the potential to be interesting and exciting as a witness to human creativity, and to the creativity that people come up with when they are concentrated on building a devotional edifice. It’s absolutely fascinating, very subtle, very sophisticated, and how could we share our excitement about that to an audience beyond the kind of people who are cheerful reading late 9th Century notation… it really is a niche audience! But we can’t sing it to them, my usual answer in such circumstances if working on Roman liturgy would be to sing this material and to talk about the impact that it can have on us and of course we can’t do that. I did briefly toy with the idea of “should we be trying to reconstruct it?” and I thought, “well, no” because that’s just a fantasy – it’s sort of theme park approach and that didn’t seem very respectful to me of the material we had in front of us. and so then the crazy idea came to me that maybe we could take something of the essence of this music, whether it’s something about it’s shape or something about it’s devotional, or spiritual, or aesthetic potential and we as scholars could communicate what we understand of that to composers and then composers could re-imagine that in their own language. So there was no intention on my part that they should be writing pretend medieval music, they should be writing music for the hear and now. But music that with luck captured something of the essence of this music from the past.

[AKB]

So here we are, back on the sure ground of new music. Effundum Spiritum Meum, I Will Pour Out my Spirit, was written in response to the call for compositions that came from Emma’s project. I caught up with the composer Benedict Todd at his flat in Bristol where we discussed his approach to the brief. Starting with how he used a forum that allowed composers and the project researchers to communicate.

Benedict Todd: I think for me it was fairly direct questions about “how do I read this? What’s this text? IS there a transcription of it somewhere that I can actually read? What are these neumes, have I read them right?” “No, you haven’t” “oh, well, thank you”

[AKB]

Okay, so kind of text-based analysis focussing on the manuscript.

[BT]

and the starting point privately for the piece for me was searching through as many of the Old Hispanic manuscripts as I could get access to online looking for texts which I thought would make a nice piece for the project.

It’s very important to me when I’m setting a text to music that the music come from the text somehow – that the music be very closely related to the text. I like to avoid music that is just a nice tune that happens to fit the meter of the words. I’d much rather look closely at what I perceive to be the meaning of the words and then music seems to come from that somehow. Trying to set that very directly into music. I take what I think is quite a direct approach to this, so for me almost all the music in this piece is really tied closely with the words in that particular line or each phrase or each sentence separately or possibly even shorter than that if there are really important words then they get picked up.

[AKB]

Okay, show us an example, where would you cite this?

[BT]

Well, there’s an important word at the end. The text says “quia ego Domiunus” “because I am the Lord” which is, by the time we get to there in the flow of the text, this feels like a crucial statement really. It’s as part of a bigger refrain – the text says “because I am with you remember these things (that I’ve just told you) because I am with you and because I am the Lord” so this is an important statement and so I’ve chosen to set it in an important fashion – it occupies and important structural place and although the harmony there is very simple… I suppose that’s represented by texture really, which divides out and I hope sort of blossoms out at that point. Just for the word “Lord” and comes back down again.

[AKB]

Remember this bit?

{ music }

Okay, so how then do you manage kind of larger scale structural decisions on this basis, if you’re kind of going moment-to-moment how does that effect the macro-structure.

[BT]

Before I can start at bar one I’ve had to consider the text quite carefully because of course with this approach the structure of the piece is inextricably tied up with the structure of the text. Which is why searching for a text took so long for this project. The piece was written over the course of about a month having spent three or four months before that looking through the manuscripts for a suitable text. An important part of that was finding a text which should be roughly the right length but also had a nice sense of structural possibility within it.

[AKB]

That’s the text… what about the manuscript and music itself. The one you chose is fairly unusual I think – you said it would have been sung for a solo cantor for instance – what else can you tell me about it?

[BT]

Its notation is quite complex by the standard of these manuscripts. There are some very long melismas in it – one syllable set to many many neumes. Which was actually one of the things that drew me to this chant in the first place; I was looking for a chant that had these long melismas in it. To me it was important to find some elements which were, if not unique to the Old Hispanic Office, at least very characteristic of this repertoire.

[AKB]

So this text unique to Old Hispanic Office in which it was sung on St. Vincent’s day dictates the musical thrust and structure. The manuscript is Leon 8 which dates from the 10th or 11th Century. Above the beautifully scribed black and red words are squiggles called neumes – dots, dashes and swoops that remind a singer of the melodic shape. this is campo aperto notation that gives us much, but not all of the information needed to sing these chants.

[EH]

The notation we have for these chants – it shows us where it goes up and down and it shows us how many notes are on a syllable and it gives us the combinations of ups and downs of those notes but we have no idea how far up or down they’re going.

[AKB]

Or indeed what the starting pitch is. So these melodic contours can be expressed in combinations of neutrals, highs and lows. Where neutral is a starting pitch and the following notes are either higher, lower or the same.

[BT]

So, as I say, I found this idea that we can read elements of this notation still… I found that fascinating. I’ve heard the Old Hispanic Office team talk about this often before and they’re always very keen to point out that even though we can read some melodic contour we can’t reconstruct what this music would’ve sounded like. Which is absolutely fair enough if you’re a musicologist but of course I’m a composer and I find that really frustrating because the first thing I want to do is sit down and read these neumes and know what it sounded like. And so I, rather cheekily I suppose, came up with a way that I could incorporate some of this melodic character. My first temptation was to think “well what could those notes have been?” not necessarily “what were they” but what could they have been and so, well actually if you look at the beginning of my piece they could have been – if you start on an A then go to the B that is one tone higher than that – that could have been the first neutral-high. An then if you start on a B for the second neutral and go up to the C# that could have been… possibly… well that’s a higher note so you then get neutral-high, neutral-high which fits with the element of the neumes that we can read. Of course, it’s almost certainly not actually what they would have sung seeing those neumes, although no-one can actually tell me that it definitely isn’t. And of course, there are many other possible readings of the neutral-high, neutral-high figure. So in fact the entry we were just talking about, the treble entry at the beginning of the piece – A-B, B-C# – that’s one possible reading. The alto part where it comes in underneath is another possible reading of that, so they start with, instead of a rising tone, they have a rising major third as the first neutral-high figure and then a rising minor third for the second neutral-high so maybe that’s another possibility. The tenors, who come in just before the altos, they have another possibility, they have a rising minor third and a rising tone so that’s another neutral-high, neutral-high figure – you can’t definitely tell me that that wasn’t something that the monks singing this – or the monk who was singing this manuscript might have sung. It probably isn’t but it’s another possible reading of it. And then the basses come in, a bit later into the piece with a similar figure, with a much bigger interval but again, it’s a neutral-high, neutral-high melodic shape of the line.

[AKB]

So perhaps, woven into the texture of this new piece a lost melody used in worship over a thousand years ago can be heard. Whether it is or not, it’s an evocative thought. And it highlights just one approach to Emma’s idea that new music might allow this Old Hispanic Office to resonate in the hear and now.

That completes this time travelling podcast. To hear the music in full go to benedicttodd.co.uk for the project see bristol.ac.uk/arts/research/oho-project

My thanks go to Stephen Darlington, director of Christchurch cathedral choir, whose voices you’ve been hearing, Benedict Todd, Emma Hornby, Pod Academy and to you for listening… thank you.

New Music series

The first piece of music in our podcast series was a nocturne inspired by the nightly shipping forecast written by Arthur Keegan-Bole.

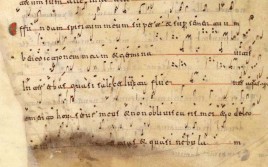

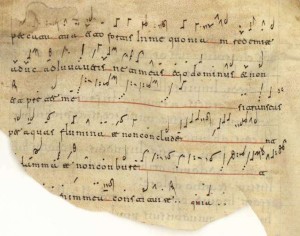

Images

The photographs in this piece are of the original manuscript containing the text and neumes for the chant Effundum Spiritum Meum.

Codex 30 (E-Mah Cod. 30), Fol 209v – 210r Liber Misticus from the Monasterio de San Millán de la Cogolla

Image from the Real Academia de la Historia, Madrid website

Picture of Portico da Igrexa de Santiago en Betanzos Jose Luis Cernadas Iglesias

Tags: Choral music, Iberian liturgy, Music compostition, Old Hispanic Office project

Subscribe with…