Transcript

Podcast produced and presented by Lily Ames

This podcast is part of our Feast for the Senses strand and is the first of a mini series on the study of Sound by Lily Ames.

Mike Wyeld: It’s a new world, it’s like the sound is in the air as everybody jokes about at the moment and it really is, we have that ability now to have people who are dedicated to thinking about how we hear and what kind of rich culture is that.

Lily Ames: Mike Wyeld has many roles a the Royal College of Art, including instructing in both the animation and sound departments. For the last few years he has run the Sound Lab at RCA. In this programme we will hear from Mike and a few of his students about how they’re breaking new sound in the academic world.

MW: So I suppose in sound at the Royal College of Art we treat it in a couple of ways.

First of all as a post production technique for filmmaking, so for animation we have quite a well respected animation department, the tracks are entirely crafted here so the students learn how to create their own foley, their own sound effects, atmospheres, that kind of thing and learn how to record it themselves. They also move on, we mix it professionally, we have full 5.1. pro tools based sound mixing facility and we also have a large sound recording area so large live room and we have everything from bands to orchestras to individual musicians to foley sessions – you name it, we do it. So that’s the more conventional part of it. In an academic sense we also think of sound in a fine art context. A few years ago, here in the UK an artist by the name of Susan Philipsz won what is generally considered one of Britain’s most biggest art prizes – the Turner Prize. It was for a work rendered entirely in sound and since then we’ve kind of seen an explosion in people wanting to work in sound for its own sake – so sound for galleries, sound for installation. And really, the way to think of it is to think of the ear temporarily displacing the eye as the seat of thinking.

I suppose in the last five or six years we’ve seen an explosion in people working in sound in a number of different ways. We’ve also seen the explosion of people being able to work with sound because of its democratization. Pro tools, the grandaddy of software for example, now works on a laptop and now avid, the company that owns it have announced there will be a 16 track version of it for free for everyone to use on earth. So, people are able to now manipulate sound, design sound and think about sound in new ways without a great deal of knowledge or expertise. They can now just get going with it. So we’ve seen that happen and we’ve also seen people become interested in some of the myths of sound, so there’s a lot of sound in terms of what it can do to the body and how it can affect you physically and we know that it does have physical effects. So we’re seeing a lot of new technology and everyday people starting to grapple with that, including artists.

LA: As sound technology becomes more accessible, students have started to show interest in the field.

MW: I’ve noticed people being able to think and speak more intelligently about sound, because there’s a lot more thinking out there about sound, so that’s the first thing. The other thing is I’ve noticed people starting to want to engage in sound, it used to be the case that you would go into a gallery and if there was a moving image work it would often be silent and I don’t think that’s the case anymore. I think people are more brave about accompanying their image with sound they’ve deliberately chosen as opposed to sound that is naturally upon the chosen image. So people have intentionally brought sound to their moving image work. I’ve also noticed people realizing the emotional power that sound has. In terms of enrollment, RCA has seen an increased enrollment over the last five or six years, and studying fine art despite the increased expense is more popular than ever. So people are thinking about that and thinking about how to express themselves in new ways and in different ways. The canvas has moved on. The canvas is anything.

So we have a variety of students at the moment who are thinking very clearly about sound. For example we have one student who is working in printmaking, around the actual making of the print and having the print move in relation to sound and that’s a highly experimental and thought provoking way to work. We’re also seeing architecture students working in sound and thinking about how sound works for buildings and how sound works in buildings just how to make a building sound nice – really thinking about sound in regards to design and how they create things. We’re also seeing people build objects related to sound to explore the way sound could potentially work in the future. We’ve had microphones and speakers for a century and the technology has moved on somewhat but not moved on in other ways, so we’re seeing students who are experimenting with sound and objects and how we will hear it in the future.

LA: Ben Dudek is one of the students from the architecture department showing an interest in sound. He’s creating built environments that emit sound.

BD: So rather than having buildings have speakers in the corner of the room emitting the sound, which seems quite old fashioned in a number of ways because now we have the potential to build it into the walls and the floors, only buildings aren’t designed to do this yet. So I am designing the buildings that can do that. I managed to find a piece of technology that allows me to turn any object from a table to a pillow, into what I suppose is a speaker. You can turn all these funny objects into sound emitting devices to use them in ways that haven’t been used before.

So what you’re hearing is a pillow rather than a speaker, and it’s the ability to hear sound through anything these days. Anything can be used as a speaker. It turns objects into speakers that you would never have imagined could be speakers, in this case, my mum’s pillow from our house that I grabbed as she was watching TV – little did she know it would be in the college exhibition a week later. If you listen to this object it can only play the medium frequencies in any song well because if it goes to high, it is not designed for that. So high signing doesn’t really work and you can hear it sort of shake when it gets to those points, which is why with all the others they sort of came together to play all their appropriate parts, like a choir.

I realized there were all these potentials at different scales and I wanted to be the concept designer for how this could be used on a much larger scale and how it could be ambitious and slightly abstract. I’m designing a landscape, a festival space for example, that emits sound from the ground, so the sound isn’t emitted from speakers anymore, it’s emitted from the surface you are walking on. That’s never been done before or thought of. The designers of this technology, when I phoned them up were like yeah it makes sense but I never thought of it.

LA: Ben’s work is so new there isn’t even an academic term for it.

BD: There’s no specific term for it, it’s just not done. I’ve talked to so many experts, sound designers in New York and LA and they’ve been pushing the limits of sound art and movement and all they’ve done is use it as a novelty scale, turning a chair into a speaker. You could do so many things with that like have seats on a bus that emit the radio, there’s so many applications. All I’m trying to do is push it to the limit and design a building that emits sound from its actual structure. This means that it doesn’t actually have to be built from bricks and mortar. It means that it has to be built from buildings that are conducive to this technology. For example, fabrics and pillows and books. For all I know, architecture can be designed anyway now, why not design a building made of paper that’s perfect for emitting sound. Now with computers and engineering technology, anything can be designed.

LA: For students like Ben who study sound, there’s an excitement in the unchartered territory.

BD: I mean it can be anything. This is the terrifying possibilities, it could be anything. I was just talking to the deaf blind association and they were like “it would be great if you could design a building and you could teach people how to feel space by the vibrations in the floors and the walls, cause all they would have to do is feel the floor with their feet and they could feel the distance to the walls”. You can build this into the fabric of society and change the way people interact. So the blind deaf people are one example, another one is alert systems, like being able to send vibrations through the earth across a landscape so that people can hear things and not through the air. Sending things through the air is really unefficient, people don’t realize but speakers are really inefficient objects. There are so many better ways of doing it like using the materials around you. Talking to Mike, the sound engineer here, he just gets so excited about all the possibilities he can imagine in his field and everyone I talk to from design product students, to everyone else gets excited. As an architect, I feel like I have the ability to use this in the most extreme way and therefore jump ahead of the game and jump back.

LA: Whereas Ben is bringing sound design into the practical world, some other students at the RCA are giving sound a more artistic treatment.

MW: The other thing we’re seeing is people going back to some of the more experimental treatments that in some ways has been lost through convention. I think there was a time in the 80s and 90s when people became almost embarrassed by experimentation. But we’re getting back to that spirit of the 50s and 60s – the music concrette.

Lily also interviews Jackie Ford and Yashu Raghunandan – you can hear more of their work here.

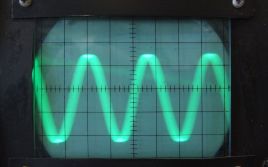

Photo: Sound Waves Loud Volume by Tess Watson

Tags: Innovations in sound design, Royal College of Art, Sound as an aid to blind people, Sound in architecture

Subscribe with…