In this blog Chris Creegan looks back at some of the key moments during Margaret Thatcher’s premiership which influenced the shift in attitudes towards homosexuality and created the momentum for subsequent legislative changes…..

There are occasions when the blogosphere becomes consumed with one event. The passing of Margaret Thatcher was inevitably just such an occasion. Within no time she was trending on Twitter. And then an avalanche of blogs and comment appeared from every part of the political spectrum.

For many who lived through her premiership and were active in politics during it, the opportunity to express a point of view was irresistible. This isn’t remotely surprising. Whichever side of the titanic struggles she waged you were on, and whatever you thought of her, they were extraordinary, and for many of us formative, days. The sheer quantity of coverage these last two weeks has been almost overwhelming. Despite many powerful memories, I didn’t initially think I had anything to add.

Two moments this week changed my mind. The first was when I read Alex Massie’s Spectator article, Margaret Thatcher: An Accidental Libertarian Heroine. In a typically well argued and original piece, Massie argues that ‘one part of (Thatcher’s) legacy that is perhaps under-appreciated is the extent to which her triumph on the economic front contributed to her defeat in the social arena’.

Advancing the argument, he suggests that this was because ultimately economic liberalism and social conservatism became incompatible, that the triumph of economic liberalism begat the victory of social liberalism as exemplified by the shift to support for gay marriage. Massie’s argument is a quite a persuasive one, at least in so far as the shift in the Conservative position on lesbian and gay equality goes.

And for me this was borne out in the second moment, which was during the debate in the House of Commons when Mike Freer, the Conservative MP for Thatcher’s former constituency, spoke. For Freer, Thatcher was an inspiration. We’re the same age, we both grew up near Manchester and we’re both gay. There, however, the similarities start to peter out.

I joined the Labour Party at university the year after Thatcher was elected and spent the 1980s campaigning against her policies. Freer is a true Blue Conservative. He is emblematic of the shift that Massie refers to, an economic liberal who is openly gay, living with his partner in the constituency where he was previously a councillor. And fair play to him. But even he might concede that in the 1980s the prospect of openly gay Conservative MPs almost anywhere seemed pretty improbable, let alone in Finchley.

There have, of course, been many other factors at work in the transformative change on lesbian and gay equality that’s taken place over the last 30 years. And I’m grateful to Massie and Freer for reminding me that one of them is to be found in both the gains and the losses on lesbian and gay rights during Thatcher’s premiership. As a young trade union activist working in local government I was privileged to be part of the struggles that ensued both in response to her policies and despite them.

The Gay Liberation Front in the UK was of course born at the beginning of the previous decade in 1970 and was preceded by pioneering campaigning through the 50s and 60s. But the 1980s was to prove a remarkable and instrumental time in the battle for lesbian and gay equality. For me, four powerful personal memories stand out.

The first took place one Saturday morning in the midlands town of Rugby in the autumn of 1984. In September of that year, the Conservative controlled council in the town decided that it wouldn’t include sexual orientation in its equal opportunities policy. There was nothing remarkable about that. Many councils didn’t have such policies and amongst those that did, sexual orientation was often absent.

But Rugby Council didn’t stop there. The council made it clear that it didn’t welcome gays working for the council at all; the council leader declared (almost hilariously in retrospect) that they didn’t want men turning up for work in dresses and earrings!

Lesbian and gay members of NALGO were at the forefront of advancing the case for lesbian and gay equality in the early 1980s; the first self organised lesbian and gay conference, now a regular and official fixture on the union calendar had taken place the year before. A coach load of us and others descended on the town for a rally in protest at the council’s stance.

It was there that Chris Smith, the MP for Islington South, began his speech to the rally saying ‘Good afternoon, I’m Chris Smith, I’m the Labour MP for Islington South and Finsbury. I’m gay, and so for that matter are about a hundred other members of the House of Commons, but they won’t tell you openly’. It seems odd now when lesbian and gay politicians, including Freer, are commonplace and their sexuality causes barely a murmur. But back then, Smith’s announcement was a brave and extraordinary moment.

The second memory that stands out occurred less than a year later. NALGO jointly sponsored a motion on lesbian and gay rights with the probation officers’ union NAPO to the 1985 Trades Union Congress. These days LGBT rights are an accepted part of the trade union agenda. Back then we were very much on the outside. Our NALGO self organised group organised a fringe meeting to generate support for the motion. Just a handful of people came along.

That said the motion was carried. It was a proud and significant moment which represented years of work by lesbians and gay men in the labour movement when sexuality in the workplace was regarded as a fringe issue at best. Just a month later, despite resistance from the NEC, the Labour Campaign for Lesbian and Gay Rights won a vote at Labour Party conference with the support of the trade unions. And one of the unions supporting the motion on both occasions was the NUM, which takes me to the third memory that stands out, Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM).

LGSM was magic; not my word but that of Mike Jackson, one of those at the forefront of the campaign. He was not wrong. It was brave, counter intuitive and unprecedented. Lesbian and gay workers from across the labour movement and beyond came together and forged a powerful relationship with miners and their families in Dulais Valley, South Wales.

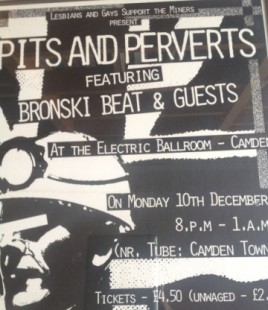

The upshot was indeed magic. Miners on the annual Pride march in London was a sight no one would have predicted just a couple of years earlier. And there was the wonderful Pits and Perverts Ball in Camden’s Electric Ballroom; a strike fundraiser to rival any other in December 1984. I still have the poster.

For me the power of LGSM was borne out when I came out to striking miners at Carcroft NUM near Doncaster. The NALGO branch I was secretary of at Westminster City Council had twinned with Carcroft. They’d heard about LGSM and it made sense to them in a way that they themselves admitted wouldn’t have been the case previously. We had come together to defend their communities: old and new struggles finding common cause at a seismic moment in labour history.

The fourth and final memory is of course Section 28. [see also the podcast ‘Don’t Say Gay’] In one sense Section 28 obviously represented defeat or at least a rolling back of progress. Just at the point when the impact of lesbian and gay campaigning was being felt in public life, albeit in just a handful of local authorities, Conservative MPs David Wilshire and Jill Knight spearheaded a campaign against ‘pretended family relationships’ and the ‘promotion’ of homosexuality by and within local authorities. Section 28 remained on the statute books for 15 years, until it was finally removed during the second Blair government as part of a wave of lesbian and gay equality legislation.

Section 28 represented a considerable setback, but by the same token it proved a galvanising moment for lesbian and gay equality. On 20 February 1988, more than 20,000 people gathered in Manchester for a Stop the Clause demonstration addressed by the likes of Sir Ian McKellen, now an openly gay national treasure.

The campaign slogan was ‘Never Going Underground’; in its attempt to halt the progress of lesbian and gay liberation, the Thatcher government had met with organised resistance on a huge scale, the effects of which reverberate to this day, not least in the form of the lobby group Stonewall which was formed the following year.

Massie’s argument that the economic liberalism of the Thatcher period begat the social liberalism we see in today’s Conservative Party is entirely plausible. And Conservative support for LGBT rights is a symbol of such liberalism. But Thatcher’s passing is also a powerful reminder that the transformation in attitudes we’ve witnessed over the last 30 years owes much to campaigns spearheaded by lesbians and gay men on the left in the heady days of the 1980s.

In fact one of the interesting features of the British Social Attitudes (BSA) data which illustrates that transformation is that during the Thatcher years attitudes worsened. Not until the mid 90s did they return to the position they’d been in when BSA started in 1983. The growth in tolerance we’re now familiar with actually dates from the early 1990s after a spike in prejudice in the mid to late 1980s. This has been linked to the arrival of AIDS, but the policies of the Thatcher government did little to temper it. Despite having been a supporter of decriminalisation back in the late 60s, Thatcher’s support for the new moral orthodoxy symbolised by Section 28 is on the record.

So Margaret Thatcher may well have been an accidental libertarian heroine. And that may in part be because a significant strand of Conservatism came (inevitably) to embrace social liberalism, though as we’ve witnessed in the recent debate on gay marriage, the battle on the right is far from over.

But all the while, two important things were happening. First the cause of lesbian and gay rights was beating down a path of resistance on the left as borne out by changes in official policy in the Labour Party and the trades unions, not it must be said without a fight. Second the Thatcher government’s policies in both the industrial and social arenas unwittingly brought about new alliances and campaigns which were to prove lasting and paved the way for much of the legislative change we saw initiated under Labour two decades later.

The left may find Massie’s argument a slightly bitter pill, just as gay Conservatives may be reluctant to accept that the equality they now embrace has its roots at least in part in the Labour movement. But in the paradoxical thing we call progress, the two phenomena are not as incompatible as they might seem. And Margaret Thatcher’s death reminds us why.

Chris Creegan is one of Pod Academy’s Advisory Group members.

Tags: Lesbian and Gay politics

Subscribe with…