Transcript

“Nature has been defined as a woman, and both nature and women were then defined into objectification and therefore into objects of violence. Ecofeminism is a celebration of the creativity of nature and the creativity of women,”

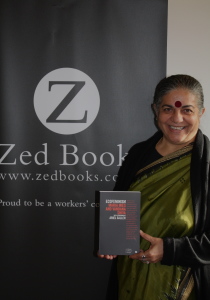

says Dr Vandana Shiva, world renowned Indian environmentalist, activist and scientist, in this conversation with Pod Academy’s Lucy Bradley about her book, Ecofeminism (co-authored with Maria Mies, Zed Books).

This podcast, which also includes the presentation by Vandana Shiva at SOAS, in October 2014, is produced and presented by Lucy Bradley.

Vandana Shiva has written many books, (including Staying Alive-Women, Ecology and Development; Monocultures of the Mind; and Soil not Oil) and Lucy started by asking her how this book, EcoFeminism, came about:

Vandana Shiva: Well the book has a very interesting genesis. Maria Mies had written Patriarchy and Capital Accumulation on a World Scale, I had written Staying Alive and that had done very well and it was the first time a title was connecting, the issues of the paradigm of development happening to women in the third world and what was happening to ecosystems in the third world. Zed [publishers] asked if both of us could do a book combining North and South perspectives. Of course we didn’t have the time to actually sit together so we just decided to write our chapters and share them every month.

And it shows there are common patterns [being experienced in these different places] because we’d write chapters and they’d be about the similar phenomena. And one was in rich, rich, rich Germany and the other was in India – which at the time we wrote it was not part of this ‘shining’ India campaign – and the book chapters then just fell into place, not because we’d planned and said we’ll write chapters on this, but because both Maria and I do thinking engaged in activism.

There’s an illusion that you have to be either an intellectual or an activist and the two don’t meet. In my view, real reflection of the world we’re in can only come from engagement in that world, not by sitting in an ivory tower and imagining you know all. When you don’t write with a vested interest, when don’t write because you are serving some master, when you write in the freedom of your mind and your spirit, with a deep connection of compassion and involvement and inclusion with every being and every person whose being trampled on you don’t get dictated [to].

Lucy Bradley: And what’s the main thesis of the book?

VS: Eco feminism is really looking at the dominant world view and structures it has created which have been driven by the convergence of capitalism and patriarchy, and looking at it from the point of view of nature and women. This is for a number of reasons, first because the oppression of nature and women served the building of this paradigm; nature was defined as a woman and both were then defined into objectification and therefore into objects of violence. Ecofeminism is a celebration of the creativity of nature and the creativity of women and it is basically in a way waking us up to see the illusion that capital creates.

The new edition of Ecofeminism of course is an update. [But] everything we said –whether it was the violence had just gotten worse and whatever we said about alternatives have just flourished better, and I’m sure if we were to reissue twenty years from now, I don’t’ know if we will be around, but the two trends will just have deepened.

LB: You have anticipated my next question, is ecofeminism gathering momentum?

VS: when we wrote ecofeminism there was a whole new generation of young women who were fed up with academic feminism which had in a way totally turned it’s back on the women’s movement. We mustn’t forget that women’s studies grew out of the womens’ movement and in the early days theorising and activism was one, and then you got into this academic strand. And what happened was at that time when young women who were engaging with the world started to get marginalized. But there’s a whole new wave now I believe because the crisis is so deep, but the beauty of this wave is when I go to universities the ecofeminism courses are half men and half women.

LB: What role can men play in this vision?

VS: The big difference between the early days of when I wrote Ecofeminism and today is at that point a lot of men took it as a personal affront. Today a lot of men are recognizing that we are all subject to violence, that we are now in the 1 percent oligarchy, most men too are suffering. But men are also suffering with the construction of masculinity, just as women suffer if they are treated as passive and a second sex, men suffer when they are defined into violence like Mussolini’s quote: war is to men what maternity is to women. War is not to men- most men want peace, most men want solidarity.

LB: Is the violence physical or also repressing the capacities that we have as humans?

VS: It is both, it is the physical violence but the repression of the potential of human beings to be beautiful individuals.

LB: So your book speaks to men and children. So your book is for …

VS: It’s for humanity, if you were to put it in a small way, I would say ecofeminism is the door to explore the best of our humanity and the best of our earth citizenship. It’s an invitation.

LB: In your introduction to the book you say that it’s a new language; the language of ecofeminism is about freedom as opposed to equality…

VS: Exactly, it’s a new language putting diversity at the centre. Because all equality that has been shaped by patriarchy and capitalism was equality wanting to be a mirror of that violent structure. So women who became liberated were Margaret Thatchers of the world, better than the men at doing the masculine domination. I think what ecofeminism allows is the flourishing of diversity with the sense of equal respect.

It is pluralism which sees the patterns of unity through the diversity. It’s about what unites us as children of the Earth. We are a child, like the trees a child, the river’s a child.

What we brought forward; me Staying Alive and Maria Mies with Capitalism on a World Scale and our combined work in ecofeminism is that the roots of violence against the Earth, the roots of violence against women and, I would add, the violence against every other, had the same roots. And the roots are wanting to create an empire, wanting to dominate, experiencing power as domination, and in its final expression power as extermination. Mussolini said very clearly; war is the highest expression of human energy and war is to man what maternity is to women. That essentialising is what is at the root of all violence.

LB: Before asking you more about what you are advocating in the book, can you say a bit more about the problems that you are challenging and then we can move onto what you are advocating.

VS: The problems that we are trying to bring forth and as the nature of the book – in very very spontaneous evolution shows – the first challenge really is the uprooting on millions in the name of development, displacement and the creation of homelessness, [where] what we have really is the world as a homeless society whereas oikos – which means home – is both the root of economy and ecology. So in the name of economy and taking care of the home we are creating a homelessness which is an absurd enterprise.

LB: And you’ve seen this directly?

VS: Oh, my god this is what I see on a daily basis. Added to it, while in the 80s and 90s the uprooting was for World Bank and IMF development projects, it then became a more structural uprooting through the rules of the economic glabalisation. And now you have another level of uprooting through the kind of impacts we see with climate change. In my region of the Himalaya 20,000 people dead last year and hundreds of thousands left homeless who haven’t yet been rehabitated Kashmir right now – a beautiful valley called Paradise on Earth devastated by flooding… the costal areas. That uprooting now in addition to development is being done through the ecological impacts of that mal development model. That’s the first big issue.

The second is the intolerance of diversity, and the third is the blindness to creativity. So that’s really what our problems are that we see and look at and give another perspective.

LB: So what are you advocating in the book, what is your vision?

VS: So what we have is a dominant economic structure which is blind to the creativity and production in nature, and actually negates the creativity and production of women. The measurement of GDP is if you produce what you consume you don’t produce. Since most women produce sustenance consumed at the level of the household, the community or the nation, its counted as zero production. So most of the work in the world is done by women, but it’s counted as zero. Extraction and exploitation which destroys our basis of life and sustenance is counted as production and growth and is what GDP measures.

So what we are talking about in Ecofeminism, as well as in our other books is that we’ve got to start recognizing nature’s economy and people’s sustenance economy. Maria uses the word subsistence. I don’t use the word subsistence because in India it gets misinterpreted to mean the poor must be kept at the level of their poverty. Maria is speaking from a rich countrysaying we don’t need to have the level of consumerism we have, but if a person is getting half the food they need I can’ t say, ‘stay at that level’. So I say sustenance which means the poor must get their full meal, and the wastage that takes place in an industrialized food system must stop because just that waste (which is half the food of the world) would ensure that no one goes hungry. So sustenance basically is producing in ways that don’t destroy the earth; that recognise the work of people, particularly women who work the hardest, and your blind economic system and your blind technologies must be corrected with the recognition of the contribution of nature and women.

LB: What is your vision of progress, to you?

VS: There’s a beautiful line by Rabindranath Tagore who says, “you watch a tree grow and its branches flourish and it’s roots grow deeper, do you call that growth progress?” No, you can’t. It is growing, but it’s not progress. But a train going from from A to B is progressing to destination B as moves closer. So progress is a very mechanistic word created for a machine world. It is not an ecological – you can’t ever define progress ecologically, but you can shift growth from measuring GDP to measuring wellbeing. Growth can be redefined in an ecological worldview. There is nothing like progress in a world that is alive.

LB: …because it’s cyclical?

VS: you don’t progress towards life you are replenishing it, rejuvenating it. Progress is a very linear concept.

LB: Where can we look to for hope, is there hope?

VS: There’s a lot of hope. On a daily basis I cultivate hope, not in an illusionary way but in a dedicated way of saving seed, spreading the infection among others for loving life on earth in all it’s diversity and pluralism, for building community at every level in a world where we are repeatedly told as Margaret Thatcher said there’s no society, there’s only individuals. But there is society and we have to cultivate it on a daily basis. And there’s hope for me in the fact that faster than the trends of destruction are the trends of a rediscovery of our humanity.

TALK BY VANDANA SHIVA

AT SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES (soas), UNIVERSITY OF LONDON

October, 2014

VS: So when Robert Montaine asked us to write a book together because our earlier books –my book Staying Alive and Maria’s book Patriarchy and Capital Accumulation on a World Scale – had been bestsellers, Roberto wanted us to do a joint book. Maria couldn’t come to India and I couldn’t be in Germany so we just said let’s write and share chapters. We didn’t first write a table of contents, the table of contents emerged as life emerges.

Basically what ecofeminism talks about is through our experience, the patterns that are emerging, both of the recognition of the violent oppression and exploitation of nature, women and other cultures; as well as the alternatives that are growing through a non-violent relationship with the Earth and among people and among genders.

I think at the heart of the transition to a more peaceful and non-violent world is a recognition that so much of the domination is though illusions which then create real violence.

Now, capitalist patriarchy – and I really think it’s between our work that we started to name this convergence that was otherwise seen as separate. There were women’s studies focusing on patriarchy, and in that focus patriarchy only existed in the past and many theories of feminism were based on the fact that the more of the world becomes intergrated in economies the less the oppression against women, or workers or people. [But] the opposite is true: corporate globalisation is leading to the errosion of workers rights everywhere and it has definitely- as my new intro shows reflecting on the new brutalisation of violence against women in India with the highlight being the December 2012 rape in Delhi, but those violent stories are growing by the day.

I have felt increasingly that we are being dominated by two major myths in our times and everything in the structure of violence is rooted in them. The first is a creation myth. Every culture has had its creation myth. In India it was about churning [?] the oceans; in the Bible it is about the 7 days of creation. Every culture has it’s own creation myth. But the creation myth of the capitalist patriarchy is that capital creates, and the word “work” has disappeared: it has become “labour”. A full independent human being works: labour is the commodified selling of labour power to capital. So now work is reduced to labour and labour is reduced to commodity. And the other is land; land is really all of the Earth’s creative force; reduced to land as a commodity, both are then made inert inputs. And it reaches the highest level with the definition of women not working- women don’t work. And I meet so many women that come up to me who are taking care of kids, they’re looking after their community and they begin with an apology saying “I don’t work”. So I say “what do you mean, “I don’t work”?”, and I make them go through their day and I say: no, you work- you just don’t work for someone else. Who pays your salary but you work to sustain life, and that’s the sustenance economy that we are trying to highlight in the book.

I’ve always preferred to call that economy the sustenance economy, in Germany Maria and her colleagues evolve the language of subsistence. And I think in Germany it’s really good to talk subsistence to remind people that you don’t have to buy buy buy everyday. Subsistence there means reflecting on what you do really need. In our context [in India] subsistence has become a word to describe the level below subsistance; food too little to sustain you, not having enough water to drink. So I use the word sustenance to both talk about the rights of people who are denied food and water, which is likely women, to have an adequate amount while stopping the waste, including the waste that comes through non-sustainable economic systems of production.

So while the first creation myth put creativity in capital which can’t create because it is not a real thing. Capital is merely another word for money. And when I try to go to the roots of capital and when did it start getting used, it started getting used with the rise of capitalism. So money has always been in society and it didn’t dominate; it was a means. If you bring out a piece of money from your wallet… So every banknote says ‘I promise to pay the bearer on demand’: it is a promise, a mediation, it’s a relationship [but] it’s meaningless in itself. It’s the promise that I pay the bearer: that when I pass on £20, the person who gets the £20 can command a certain amount of resources, or goods, or services through it. So it’s a mediation between real people and it’s a mediation that is an entitlement and purchasing power to real things.

This redefined as capital is a construct. The original word for the roots of capital of are ‘caput’, and caput used to mean – I know it also means in slang it’s gone caput- but in Latin it means heads, the number of cattle. The number of head of cattle you could actually count, but capital now has been made this mysterious force of creation, and this mysterious source of creation takes labour and gives value. I’ve had debates with biotech industry where they say; ‘by the time you’ve finished the corn that the farmer grows will have no value. It’s the genes we own in that corn that will have value. And then the same goes for nature. Nature creates everything: the air we breathe, the water we drink, the food we grow in collaboration, and yet it’s being turned into dead matter. All of reductionist mechanistic science had only one philosophical underpinning: nature is dead matter. So what ecofemisism is is removing that illusion of capital as creation, and nature and human beings as inert and passive, and realising that capital is in fact dead and creativity lies in the work of people, creativity lies in the work that nature does. Nature, without our help, carries on.

The ultimate aspect of the creation myth is what has preoccupied me for the last three decades, beginning with my attending a meeting in 1987 with corporations who had brought us agri-chemicals [who] now said we’ve got to own the seed; to own the seed we’ve got to own patents; to have patents we’ve got to do genetic engineering and to do this world wide we have to have an international law which became the Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights [TRIPS] of the World Trade Organisation. Having worked to protect diversity in the Himalaya with the Chikpo movement- but biodiversity has been my dedication and my passion- to have those companies come up to me and say now we will declare we are the creators because a patent means you have created something. A machine as an invention is put together from scratch, an automobile is put together – metals, rubber, eletrical material, engines – a plant is not put together. A seed is not a manufacture. But just like capital was defined as a creative force, a whole architecture has been built to define a gene as a creative force of an organism. A gene is moved – usually there are only two: toxin genes herbicide tolerant BT toxin- but moving a gene doesn’t create a plant; the plant creates itself. So this idea of patenting life is the ultimate creation myth. And we could, if you find intellectual property rights and Article 27 3b of the TRIPS Agreement too complicated – and it is – GMO is a summary for God Move Over if you believe in God, otherwise Creation Move Over. But with this creation myth – and the creation myth is now reaching the levels where the next step of this globalised green economy is , besides the fact of owning and patenting life, there is a serious effort at owning ecological services and functions that nature provides. If you want to go further into that we could discuss it later.

But related to the creation myth is the production myth. And the production myth begins of course with that illusion of capital as the creative force of production and it them was elaborated further with another construction called the GDP. It’s a measure that is defined in a very arbitary way. It was first used during the Great Depression in the United States to somehow mobilise public resources in order to overcome the economic crisis. Then it was brought to the UK as a way to mobilise resources for the war. And the definition in national accounting systems for measuring the GDP is: if you produce what you consume you don’t produce. So [according to this logic] nature produces water and the recycles that water so of course she doesn’t produce water but when you privatise a water supply you are now producing water. I don’t likeplastic bottles, I’ve being carrying this one for two weeks now filling it with the tap water wherever I can but this one is nice because it says ‘100 per cent of our profit fund water projects in Africa”. But if you look at a Coca Cola bottle it always says produced by Coca Cola, and they are not meaning the plastic, they are meaning the water inside. All they have done is steal the water from somewhere. I was invited, and this had happened much after we wrote Ecofeminism, a village in South India called Platumada in 2002 a group of women invited me to join them in solidarity in the fight against Coca Cola. So I went because I didn’t know the village; I couldn’t understand how water and Coca Cola were connected, and I couldn’t understand how a group of women in a remote village were taking on this big giant and I really went through inquisitiveness to find out. And I arrive and I find less than a hundred women and these were tribal women and they were being led by a sixty-five year old woman called Mylama and she greeted me with a bow and arrow and that was a gift to me, and there were five hundred policemen on the other side of the road. I thought ‘these guys are going to butcher the women and no one will know’ because Coca Cola pays so much in advertising that no newspaper was covering what was going on. What I learned through that protest was: for every litre that goes into a bottle 10 litres is destroyed. And 1.5 million litres is extracted [as] a minimum – 1.5 to 3 million litres – in any Coca Cola plant whether its to just put bottled water or whether it’s to put a little phosphuric acid and we found out the Coca Cola in tropical countries uses phosphuric acid everywhere for that ‘ting’ – you know when they say you get the kick: it’s phosphuric acid that gives you the kick – and they use antifreeze that you put into cars so that the temperature can be lowered more in that heat, and you feel even colder. So nobody knew what was going on. And I called up some local politicians and said ‘you must be ashamed of yourself here are these women fighting and you are not there, and I called up a powerful regional paper and said you should be here’, and next time your newspaper must sponsor an event and cover this. Once they broke the silence then everyone else had to start covering this movement [and] by 2004 the women had shut down the Coca Cola plant. So this [is an] illusion that Coca Cola produces or creates water. And now because of these movements I think we have shut down four plants. Pepsi and Coca Cola now have advertisments that I see on paper napkins on airlines [reading] we put back more water than we take. You can’t put back more water than you take: it’s impossible, even nature doesn’t put back more water than she puts in.

So there is this very false way in which we are made to think of a world growing in the hands of capital while really the world is shrinking in the hands of capital. It’s shrinking in terms of nature’s economy and her capacity because every time an ecological process or an ecosystem is disrupted, nature is poorer and nature has an economy. And everytime a community looses its resources, either directly through appropriation through the theft of seeds, the theft of water, or the theft of land grab- an issue that is now so big in Africa- and again if you see the justifications of land grab they will always say ‘the peasants and the pastoralists don’t generate value’. But they generate a lot of value if measured in nature’s economy and people’s economy. They don’t generate value as profits in a global economy controlled by multi-nationals, but that is not a value it’s a disvalue: it’s a disvalue because it’s based on the rape of nature and the distruction of communities. And we have a very large section in our book on creating a world of uprooted people. Displacement has become the norm, displacement has become the norm of economic growth.

So what are the possibilities and potential that ecofeminism, which is not an ism –its merely a window to see the world differently, and that seeing the world differently has become vital because the capitalist patriarchy – based on erasing the contributions of nature, women, and people – is creating a world of fear? The fear of scarcity, the fear of the other- everything you look at in the Middle East today is the culture of fear that is grown out of destroying local cultures and local economies. Egypt[‘s protests began] with the price of bread [and] look at where it’s been taken. Syria the protests were about drought and farmers not having a crop and look where it’s been taken. And its been taken not by the people themselves but its been taken my the world, partly out of ignorance and partly out of creating the final market; the final market of capitalist patriarchy is the economy of war. There’s war taking place against the Earth and women but it’s indirect. Now it’s direct and so much of what peace activists and peace studies study is how the growth of arms trade is leading to so much violence. Now they are producing more arms than they need in war, so you might have followed the violence in St Louis: two black youth killed. Part of it is the police there looks like army now because all the surplace arms have been given to police stations and all the surplace arms are being given to schools because violence in schools is big in the United States. So now they’re thinking the way to end violence is turn every place in to a war zone.

GDP is such a fictitious measure, for example the UK was doing very badly in GDP – its growth- but suddenly its growth increased by 5 per cent; £10 billion. Did you start to manufacture more things? No. Did more people get work? No. They just decided let’s count the sex and drug trafficking as economic activities. And those are huge economies and in fact the more you break down society the more those economies of crime grow. And those economies of crime are then the place where the new GDP growth starts to happen because it has no value attached to it to see whether societies are better off with a lot of drug trafficking or not.

How do we move beyond this crisis created by illisions, illusions that then predate on the real world, illusions like the fictitious finance, and this city makes a big contribution to that fictitious finance; the part that’s called the City is not all of London, it’s just the place where speculation and casinos play. And 70 times more money is created through fictitious violence which is then used to bet further by grabbing land in Africa, speculating on food making food prices grow, speculating on everything. As I said the next step that they are trying to get is speculating on functions of nature- I mean they really want to own the capacity of the green leaf in the forest to absorb carbon dioxide and release oxygen. They can’t take it because it’s not takeable- it’s a process that can only happen in the tree itself. But what they can do is appropriate that function and sell it as a commodity on Wall Street. The financialisation of ecological processes is what allows it to become a tradeable commodity

It doesn’t have to be that way. Ecofeminism is about helping us remember that nature creates, people create, women are a huge creating force on this planet and the wonderful aspect of it is when we co-create with nature, not only do we meet our needs, we rejuvinate nature. The fiction of capital being a creative force can only expolit and deplete nature. Co-creation with nature actually gives us more fertile soils when we do organic farming; it gives us more biodiversity when we conserve seeds; it gives us more water when we conserve water; and it’s the single biggest solution to the greenhouse gases that are being emmitted – 40 per cent of which come from an industrial agricultural model.

So I think we are at this cusp where we need to redefine production and creativity and intelligence, and we need to redefine land as labour and labour as creative people and creative nature – and not have them as inputs into a linear system of exploitation processing junk and commodities – into a circular system where we produce what we need, all the food water and clothing, and in the process have an output, not an input, of creative, meaningful work for all. It should be defined not as something that goes into an economic production model, but as something that comes out of a good economy: meaningful work for all and with it a rejuvinated nature.

Earth care has to become the biggest work that we engage in and a by product of Earth care is all the human needs we need. That’s the kind of opening that ecofeminism creates and the reason it both creates such inspiration as well as fear is because it goes to the real foundations of all vilence. Most other perspectives touch a bit [for instance] workers’ rights will touch on the workers’ exploitation, the environmental movement will touch on what’s happening to the environment. But ecofeminism goes to [the false assumption on the basis of which the architecture of capitalist patriarchy rests, and that architecture is then justifying all violence in the name of progress and growth and ecofeminism allows us to make a shift and celebrate our creativity and our freedom and that is the only way we will be able to make a leap beyond this predictable collapse at the ecological, political, economic, social level that we are living through. We are not talking about it in the future; it’s happening now.

Photo By Michael Cannon (Comprock) (http://www.flickr.com/photos/comprock/5256267877/) [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Tags: Ecofeminism, Ecology, Feminism, Vandana Shiva

Subscribe with…