Transcript

The number of couples seeking fertility treatment is rising every year. But donor assisted conception poses huge ethical and human rights issues. Up until 10 years ago, sperm donors and women who donated eggs had a right to remain anonymous. Then the law was changed in 2005 giving donor conceived people the right to information about their donors. Most people agree that this was a milestone to be celebrated, but does it go far enough?

This podcast explores the issues. it is drawn from an event organised by the Progress Educational Trust and is introduced by the Chair of the event, Charles Lister, Chair of the National Gamete Donation Trust, and former Head of Policy at the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority. He quoted a speech by the Public Health Minister, Melanie Johnson made in 20014,

‘Clinics decide to provide treatment using donors; patients make a decision to receive treatment using donors; donors decide to donate. Donor-conceived children, however, do not decide to be born – is it therefore right that access to information about the donation that led to their birth should be denied to them?’

This quote encapsulates the essence of the debates that led to the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (Disclosure of Donor Information) Regulations 2004, which allow donor-conceived people born from donations made after 1 April 2005 access to identifying information about their donor on reaching the age of 18. It also set the scene for a series of lively presentations from a panel of five experts, who took to the stage to offer their perspective on the impact of the legislation.

First to speak was Juliet Tizzard, Director of Strategy at the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), who gave the regulator’s perspective on the change in law. Tizzard identified the lack of reliable outcome metrics in relation to donor conception as a key challenge, and hindrance, to accurate impact evaluation of the 2004 regulations. She also opined that the assessment of post-regulation sperm and egg donation trend as proxy measure of impact showed a gradual but steady increase in number of new donors registering in the UK – a reality that is a far cry from the doomsday prophecies of the early critics of the law, who predicted the possibility of severe donor shortages arising as a result of the end to donor anonymity.

Next on stage was Dr Jo Rose, a donor-conceived adult who won a landmark court case that contributed to the decision to end donor anonymity in the UK. In her presentation, Rose argued that donor-conceived children should, as a matter of course, have more support and the right to access full and complete information about their genetic parent, particularly because ‘wrong and incomplete medical history kills people’. She also argued that a lack of retrospective access to identifying information means a number of donor-conceived people born before April 2005 live the rest of their lives ‘tortured’ by not knowing who their genetic family is.

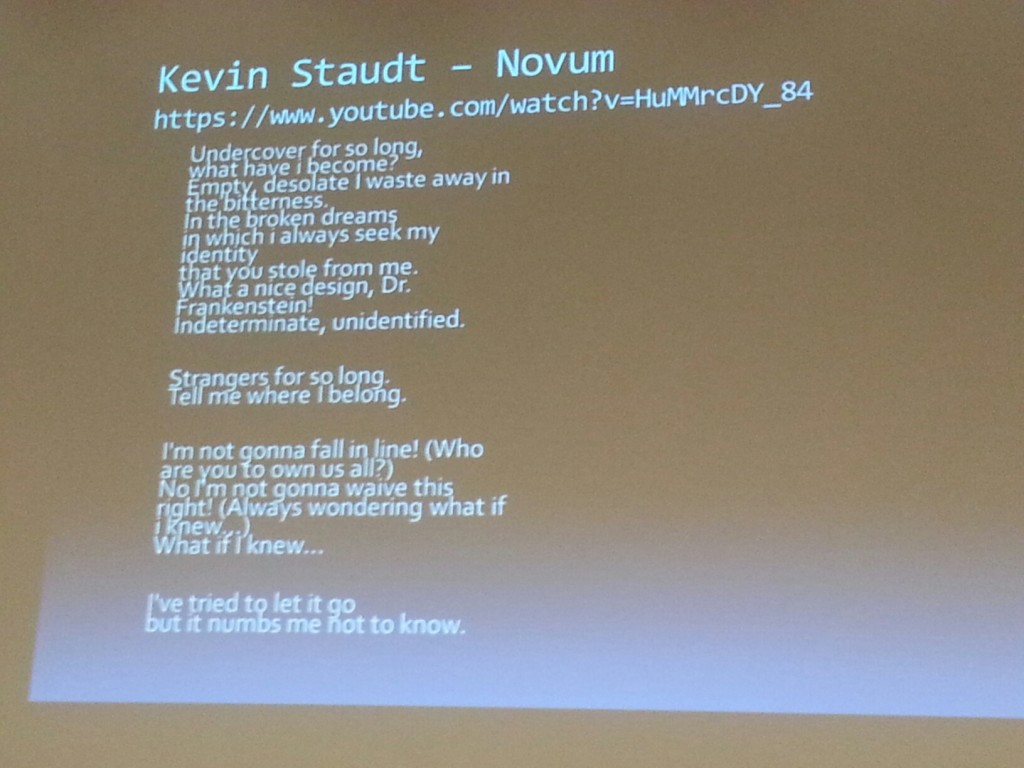

‘Why then should we have legislation that protects the rights of donors but ignores the rights of donor offspring?’ she asked the audience, and quoted Kevin Staudt’s song, Novum:

Rose’s presentation gave a personal note to the debate and made it easy to appreciate the rationale behind her call for retrospective disclosure of donor identity. According to her, more needs to be done to ensure ‘equality and respect for genetic kinship and identity for all groups of the society’.

Eric Blyth, Emeritus Professor of Social Work at the University of Huddersfield, also made a case for retrospective disclosure of donor identity. Using data from the HFEA, Professor Blyth argued that the lack of retrospective access to identifying donor information means that upwards of 20,000 donor-conceived people born between 1991–2004 in the UK are denied the right to learn the identify of their donor.

Blyth also argued that, since the data presented by Tizzard showed that more than 150 donors who donated prior to April 2005 have chosen to waive their right to anonymity, protecting donor privacy may not be seen as equally important by all of those donors.

Venessa Smith, the Quality Assurance and Patient Coordinator at the London Women’s Clinic, offered insights from the perspective of the service providers. She reported a change in sperm-donor demography and composition from ‘young men donating for “beer money” pre-2005, to young professional males with families donating purely for altruistic reasons post-2005’. This, she argued, may be attributable to a post-2005 paradigm shift that resulted in a greater focus on the welfare of the donor-conceived child, rather than merely the successful outcome of the assisted reproduction process.

Smith also argued that the routine support and counselling offered to post-2005 donors ensures that ‘donors who do make a donation are the right ones for the patients’. This has contributed to a significant increase in number of donors at the London Sperm Bank and London Egg Bank, she reported, such that patients now have a variety of choice and no longer have to wait long for donors.

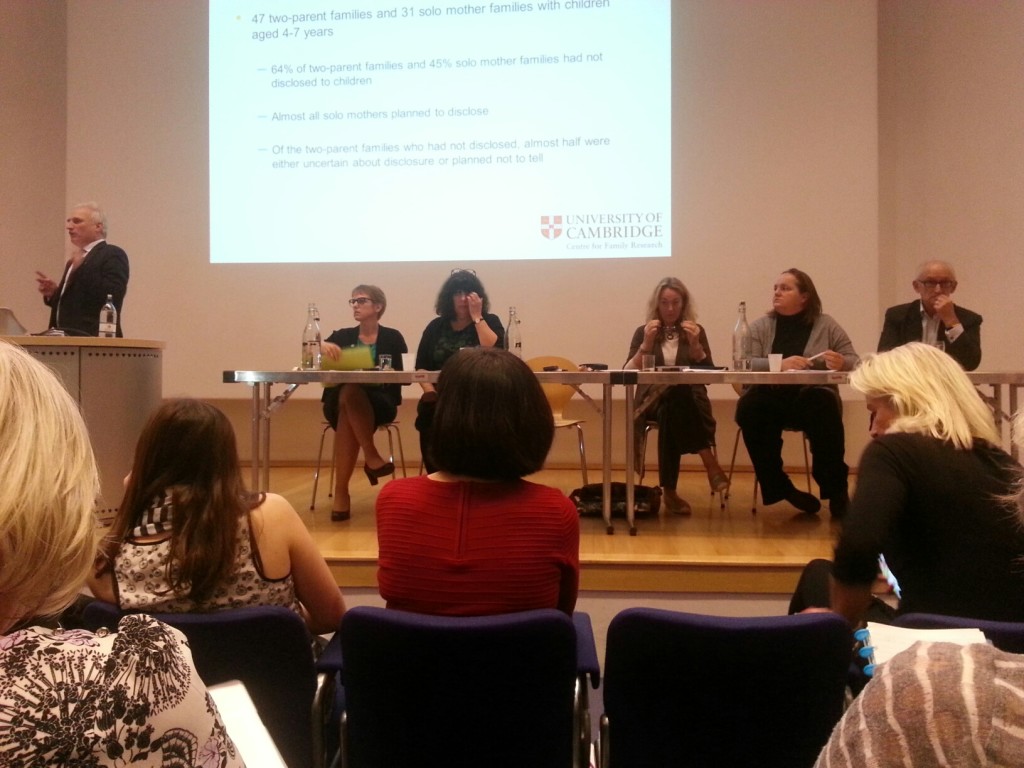

The last presenter for the evening was Susan Golombok, Professor of Family Research and Director of the Centre for Family Research at the University of Cambridge. Her presentation focused on the how disclosure of donor conception in the UK had changed over the past 30 years.

Professor Golombok discussed two longitudinal studies. The first followed 111 donor insemination (DI) families who had children born in the mid-1980s, and another conducted some 15 years later followed 50 DI families and 51 egg donor (ED) families. In summary, in the earlier study fewer than 10 percent of parents had disclosed by the age of 18, whereas in the later study 67 percent of ED parents and 41 percent of DI parents had disclosed by the age of 14. So while it was encouraging to learn that the number of parents disclosing has increased, it was also apparent that parents who initially indicated willingness to disclose donor conception to their children did not always go on to do so.

When considering the welfare of the child, it was reassuring that no child responded to disclosure in a negative way, and no parents regretted disclosing.

The panel also fielded some questions from the audience, which centred on the practical aspects of donor disclosure. Emma Cresswell, a donor-conceived adult in the audience, insisted that it was no longer right to withhold information from donor-conceived adults. She argued that disclosure of donor conception should be an ethical duty, a parental responsibility and a legal requirement. She suggested that inclusion of identifying donor information on a donor-conceived child’s birth certificate would guarantee this disclosure.

A number of audience members backed up this call for a review of current legislation to encourage disclosure, as and to remove donor anonymity retrospectively. Others raised questions about the ethics and practicality of enforcing the disclosure of donor conception, and pointed out that retrospectively lifting donor anonymity breaks promises made to people who donated before 2005.

Juliet Tizzard said that, in her view, the best approach was to support parents of donor-conceived children to encourage disclosure, rather than seeking to mandate it. Caroline Spencer, a behavioural psychologist and trustee of the Donor Conception Network, also emphasised the need to educate parents of donor-conceived children on the importance of disclosure while supporting them with practical tools and tips.

By the end of the evening, it was clear that emotions around the debate on donor anonymity run high, that neither the audience nor the panel would reach a consensus, and that issues surrounding donor anonymity and disclosure will continue to be hotly debated.

This article is based on the piece by Arit Udoh in BioNews, the online magazine of Progress Educational Trust.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3XG0n83yqv4&feature=iv&src_vid=HuMMrcDY_84&annotation_id=annotation_2543745055

Tags: Donor anonymity, Donor conception, Fertility treatment, IVF, Novum

Subscribe with…