Transcript

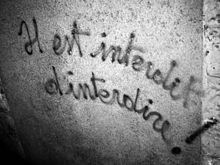

This is the second in our series based on Rod Stoneman‘s book, Seeing is Believing: the Politics of the Visual. In the podcast, Rod analyses the subculture of graffiti and its social and political significance, using this Banksy graffito in Cleveland Street London W1 as his jumping off point.

The podcast is produced and presented by Esther Gaytan Fuertes.

Rod Stoneman: This image is a photograph taken in a central London street and it shows a graffito made by Banksy. The original starting point for street art and for graffiti —obviously there are precedents in ancient cultures in different times and different places, quite apart from Pompeii and Herculaneum and Greek cities in Western civilisations, it’s not just a phenomenon of the West, one could even look further afield to Mexico, where contemporary political graffiti stencilled in Oaxaca, for example, since in 2006 when there there was a teachers’ strike, connects with the mural painting of the 1920s and 30s when politicised painters worked on art that would be more open and accessible because it was painted on walls, Riviera and Siqueiros being two of the leading ones, and perhaps even there’s resonance before that in Mexico with other civilisations, the Mexica or the Mayan civilisations used highly coloured paint on some of their wall decoration. So its most current versions in the last fifty years, tagging and subway graffiti in New York and painting in the street in Los Angeles, have spread through to most cities in the world.

Politicised use of graffiti is perhaps a narrower tradition but still an interesting development from, say, an Australian group in the seventies called with the marvellous title BUGA UP which was an acronym standing for Billboard Utilising Graffitists Against Unhealthy Promotions, and they devised kind of long poles that could be used to take a spray can 10 or 15 up a billboard to make modifications that changed it. May’68 in Paris was obviously an explosion of art in a very imaginative and engaged way.

Perhaps one should also remember the troubles in Northern Ireland with the mural work that’s taken place there.

So these different and diverse moments of politicised street art come through to contemporary subvertisement, as a neologism to talk about what the French situationists might have called détournement, taking an original image and changing it by word or visual modification. And they all show potential for counteraction, potential for an alternative and indeed more democratic two-way communication. There is a word for communication studies that is, the phatic, which is about opening a channel of communication where you pick up a phone and say, ‘are you there?’ and ‘yes, I can hear you’ and that’s the beginning of a conversation. That’s perhaps the most hopeful and optimistic dimension of graffiti in its various forms at the moment that suggests that the visual landscape that we encounter in cities does not have to be dominated —well, after architecture— by publicity and advertising, that actually artists and young people more generally can make visual material which has the power to make people think, reconsider, change and respond a more open process.

If you want to know more about the politics of the visual, here is another in the series –

Seeing is Believing: The politics of the visual is published by Black Dog (UK £19.95, US £29.95) It explores the complex and reciprocal dynamic between world and image in this most visually mediated society. Everyone ‘knows’ images can be false or deceptive, but we all live and work in constant denial of this idea and its implications. In a world saturatedwith media we act as though we are immune to their effects.Structured in six parts “History/Politics”; “Art/Culture”; “Film/Television”; “Products/Possessions”; “The Quotidian/The Strange”; “Verisimilitude/Delusion”—the book analyses clusters of images to explore differentiated themes of pictorial operation including photography, graffiti, painting, film and television. Seeing is Believing is an invitation to an intimate voyage that is permeable to the world’s upheavals, exploring the potential for contemporary forms of artistic practice to create new spaces for active participation in culture and society.

Tags: Banksy, Cultural studies, Graffiti, Media studies, Street art

Subscribe with…